Beyond the Prison Walls

Introduction

In December 2023, a chance encounter in Florence between Olivia Blakeman, a British tourist, and an Italian businessman by the name of Lorenzo Ferraro led to an interesting conversation. Lorenzo told her the story of how in the Second World War his grandfather, an Italian army officer by the name of Captain Franco Tesi, had helped a British soldier who had escaped from an Italian prisoner of war camp and was attempting to return to the Allied lines.

Captain Tesi had obtained the name and address of the soldier, he was a Mr. J. Larkin of 4 Georges Terrace, Orrell. Unfortunately no further contact had been made between the pair since the war. On her return to the UK and intrigued by the tale, Olivia reached out to Wigan Local History & Heritage Facebook page for assistance in tracing the next of kin of the mysterious Mr. Larkin.

After some detective work the soldier was identified as John Cecil Larkin, and soon his son Andrew was found to be living in Parbold. Andrew was put in touch with Lorenzo who produced documents and photographs, providing an opportunity to try and piece together the events that had happened in Italy some eighty years previously.

This is John Larkin’s war time story based on his regimental history and through the eyes of his battalion’s daily war diary as he travelled through nine countries on his journey to the front line and eventual capture. His time as a prisoner of war in Italy is told partly by his own reminiscences and of written accounts by fellow prisoners who were incarcerated with him. It also explains the bigger picture of the political and military situation of the war in North Africa and Italy.

Early Life

John Cecil Larkin was born 14 September 1920 at 4 Georges Terrace, off St. James Road, in Orrell, near Wigan. He was the youngest of six children, four boys and two girls, born to William Henry Larkin and Catherine (nee Mullen). One of his sisters, Cecilia Alice died in 1918, aged eleven, two years before John’s birth. In 1926 his older brother Gerard died of meningitis aged eight.

The 1921 census shows his father William’s occupation as a coal miner at Sutton Manor Colliery in St. Helens. Later he transferred to Garswood Hall Colliery in Ashton in Makerfield where he worked as a metal man, servicing the tunnels and rails.

John was a keen sportsman like his father William who had played rugby league for Swinton Rugby League Club. John played for both St. James’s RC football and rugby league teams in Orrell.

John Larkin, middle row 2nd right playing for St. James RC football team

On leaving school at the age of fourteen he gained employment with the London Midland & Scottish Railway at the busy Chapel Lane goods yard in Wigan. The 1939 Register taken at the start of the Second World War shows that John was a ‘hooker on’, whose job was to literally couple the goods wagons together. He later progressed to being a goods porter, loading and unloading wagons and attaching and detaching the goods labels, ensuring they matched with the serial numbers of the goods wagons.

Grenadier

On 11 November 1940, with the Second World War just over a year old, twenty year old John enlisted into the Grenadier Guards at Wigan. A week later he reported to the Guards Depot at Caterham Barracks in Surrey. His conduct sheet shows that the only blemish on his disciplinary record in training was on 18 January 1941 when he was deprived of 14 days’ pay by his commanding officer for being out of bounds and not in possession of his pay book (AB 64 Parts 1 & 2). On completion of his basic training on 6 March 1941, 2621936 Guardsman Larkin was transferred to the Grenadier Guards Training Battalion.

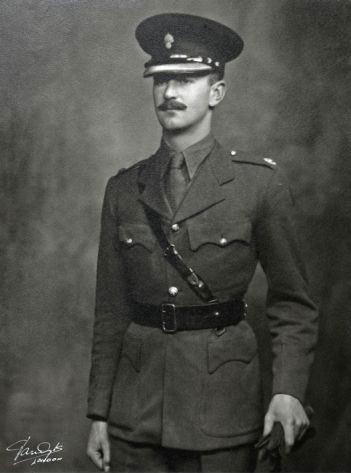

Guardsman John Larkin, Grenadier Guards

During the Second World War the two Princesses, Elizabeth and Margaret were evacuated to Windsor Castle and it once again became a fortress. Despite the wishes of Prime Minister Winston Churchill who wanted the Royal family to sail to Canada, their parents King George VI and Queen Elizabeth remained at Buckingham Palace, visiting their daughters at the castle at evenings and weekends. As a member of the training battalion John was tasked with protecting the Royal family, as part of the Infantry Company who were based at Victoria Barracks in Windsor.

Eight months later in October 1941 a new battalion, designated 6th Battalion Grenadier Guards was raised at Caterham, the nucleus coming from the Chislehurst detachment of the holding battalion. Two hundred additional men, including John came from Windsor. The new unit was commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Archer F.L. Clive MC. an outstanding soldier and leader who had won the Military Cross at Dunkirk and was to receive two Distinguished Service Orders in North Africa and Italy. John was assigned to No.10 (Machine Gun) Platoon led by Lieutenant J.K.W Sloan of No.3 Motor Company, which was under the command of Captain the Viscount Anson.

On her sixteenth birthday, 21 April 1942, Princess Elizabeth was appointed Colonel in Chief of the Grenadier Guards following the death of her predecessor, her great-great-uncle and godfather, the Duke of Connaught The following month John’s battalion was honoured by a visit from Princess Elizabeth, the first visit that the new Colonel had made to any of her battalions.

Princess Elizabeth inspecting the Grenadier Guards in 1942

From the outset the 6th Grenadiers was trained as a motorised battalion for use in desert warfare, to be dispatched to the Middle East as soon as possible. As part of his training John, who had a love of motor bikes, was chosen to attend a three week long dispatch riders course at Southgate in London, commencing 8 January 1942.

Overseas

The 6th Battalion Grenadier Guards was earmarked to join the 201st Guards Brigade, consisting of the 2nd Battalion Scots Guards and the 3rd Battalion Coldstream Guards, who were serving with the Middle East Force. They had long asked for a third battalion to reinforce the brigade. As a new battalion the Grenadiers were assured that they would be given time to get to know their new sister Guards battalions and continue with their military training until they were battle ready. To bring home the reality that the battalion would be heading off for war John signed his last will and testament on 6 February 1942, nominating his mother as next of kin.

Guardsman John Larkin on home leave in Orrell

On 16 June 1942, the Grenadier Guards youngest battalion embarked at Liverpool on HMT Strathmore, a P&O liner and mail ship of 23,000 tons which had been converted to a troopship. After calling at the Clyde to rendezvous with a convoy it headed out into the Atlantic for the long journey round the Cape of Good Hope, the Mediterranean route being closed at that time to all but the Malta convoys. The 6th was the first Grenadier battalion to go overseas since the evacuation of Dunkirk in the summer of 1940. After three days at sea secret orders were opened and apart from a select few who already knew, the troops were informed of their destination.

P & O Liner SS Strathmore which carried 6th Battalion Grenadier Guards to war

After a stopover at Freetown in Sierra Leone, the Strathmore finally dropped anchor on 8 July in the harbour at Durban in South Africa. When Britain declared war with Germany on 3 September 1939, the ruling United Party of South Africa led by James B.M Herzog wanted South Africa to remain neutral. As the descendant of a German immigrant Herzog was an admirer of Hitler and believed that Nazism was a system which had to be adapted in South Africa under a ruling dictator.

However his coalition partner Jan Smuts opted for joining the British war effort. Smuts’s faction narrowly won a crucial parliamentary debate, and Herzog stood down after fifteen years. Smuts then became the prime minister and South Africa declared war with Germany.

It was in this still delicate political situation that the Grenadiers arrived in South Africa. However they managed to continue training, perform ceremonial duties and successfully fly the flag. Lieutenant Colonel Clive who had previously served in South Africa as part of the British Military Mission ensured that the good will visit was a success.

After a stay of five weeks the battalion continued on the second leg of its journey to Egypt on board the 10,000 ton troop ship HMT Ascanius, arriving in Suez on 8 September 1942. This journey was not as comfortable as the journey south, with rougher seas and temperatures of over 100 degrees Fahrenheit below decks as they recrossed the equator and entered the Gulf of Aden. On arrival at Suez the battalion was transported to a tented camp at Qassasin between Cairo and Ismalia.

After initially defeating the Italian XXII Corps in January 1941, the 8th Army under General Wavell had been pushed back over 300 miles by General Erwin Rommel’s Afrika Corps. Rommel, nicknamed ‘The Desert Fox’ was now threatening Egypt and the Suez Canal. The 8th Army, now under the command of General Bernard Law Montgomery was holding the line at El Alamein, some 167 miles to the west of Cairo.

The Coldstream Guards and Scots Guards of 201st Guards Brigade, with whom the Grenadiers were to become part of had suffered heavy casualties in the siege of Tobruk. The remnants of the brigade were taken out of the line and reformed in Egypt. On 25 August 1942 they were sent to Syria to guard the oil pipelines at Kirkuk.

Flying the Flag in Syria

On 3 October the Grenadiers followed on behind its sister battalions, first by rail then by road across the Sinai Desert, through Arish, Gaza and Tiberias to a camp at Qatana, in the foot hills of Mount Hermon, eighteen miles south west of Damascus. Here the brigade was to spend the next four months. The windblown and flyblown conditions took a toll on the health of the newly arrived infantrymen, ensuring that every day up to sixty men at a time were hospitalised with dysentery, jaundice or malaria.

In November the brigade undertook a tour of Lebanon and Northern Syria. Its purpose was political, to impress upon the inhabitants the strength of Anglo-French unity and the fact that there was a sizeable body of first-class British troops within reach of the remotest part of the country. At the same time, with the appearance of the brigade on its southern borders it was hoped to deter the Turks from allowing German or Italian infiltration into Turkey, from where they could threaten the French troops in Syria.

First the brigade travelled to Baalbek in Lebanon, some 56 miles to the north. Here the Grenadiers detached No.2 (Anti-Tank) Company under Major A..J.E. Gordon to Beirut, where they paraded on Armistice Day before French General Georges Catroux. From Baalbek the brigade motored 180 miles, through Homs and Hama to Aleppo in northern Syria, where all three battalions marched through the centre of town.

From Aleppo it was onto Djerablus, here there was another ceremonial march which ended at the bridge over the River Euphrates which divided Syria from Turkey. They then motored 183 miles to Deir ez Zor, crossing 120 miles of desert on the way. This gave the brigade an opportunity to practice land navigation in the inhospitable terrain. At Deir ez Zor, owing to a smallpox epidemic a foot march through the town centre was prudently cancelled in favour of a drive past the French commander.

Back at Qatana, with the onset of winter upon them the guardsmen settled down to the routine of camp life. From December through to February the conditions in Syria were not too dissimilar to the UK with snow and ice closing the mountain roads and temperatures below zero at night.

The troops attended courses, were taught how to lay and lift minefields by the Royal Engineers, and went on training exercises to perfect the tactics of desert warfare. Regular divine service was held by the battalions chaplain, Revd W.R. Leadbetter. For recreation the usual sports were played and donkey and camel races were held. Local leave was allowed in nearby Damascus and on occasions a mobile cinema visited the camp.

On 7 January 1943 John took part in a motorcycle reliability trial. This was a long distance endurance event covering a fixed distance in a set time, stopping at a series of checkpoints to complete tasks which tested riding skills. John’s team was placed fourth.

Three days later John was in a party of four officers and 350 other ranks that left for Tripoli in Lebanon to mount guard on the port facilities. Whist John was in Tripoli on guard duty he was unaware that tragedy had struck at home. On 12 January his father William was killed in an accident at Garswood Hall Colliery when a fall of roof dislodged two girders, pinning him to the floor.

The Grenadiers returned to Syria on 23 January, and on the 27th a warning order was received from brigade headquarters informing them of an impending move to join the 8th Army in the Western Desert.

The Long Trek to Tunisia

On 7 February 1943, 201st Guards Brigade was finally on its way to war and moved from Qatana to Tulkarm in Palestine. The battalions then retraced their steps through Egypt, via Asluj and Ismalia back to Qassasin near Cairo, where they had set off from four months earlier. Here they were equipped with new vehicles and equipment.

Between 23 October and 4 November 1942, whilst the Guardsman were in Syria the Second Battle of El Alamein had taken place in the Western Desert. It was to be the climax and turning point of the North African campaign, where the Axis armies of Italy and Germany suffered a decisive defeat by the British Eighth Army. The Afrika Corps, was pushed westwards all the way back through Libya to Tunisia.

At a steady 15 miles per hour for eight hours a day the long column of vehicles of 201st Brigade snaked westward along the International Coastal Highway in the wake of the 8th Army. As a dispatch rider John was busy riding up and down the convoy delivering messages between the various levels of command and units.

On their journey they passed the sites of famous battles that had been fought in the Western Desert over the previous eighteen months, including El Alamein, Mersa Matruh, and at Tobruk, where they spent two days. Maintenance was conducted on vehicles and equipment, personnel bathed in the sea and the anti-tank platoons got the chance to fire their guns at derelict tank hulks.

From Tobruk the march continued through Derna, Benghazi, and Ajdabiya. On 24 February the brigade passed under the Arco dei Fileni, a familiar landmark to soldiers of the 8th Army, who nicknamed it ‘Marble Arch’ after its London counterpart. The RAF had a landing strip nearby from which to conduct operations against Axis Forces.

A Humber armoured car leads RAF lorries through the 'Marble Arch'.

The 103 foot high monument of Neo Classical design was built by the Italian dictator Benito Mussolini in 1937, on the border between Tripolitania and Cyrenaica. (In 1973 it was destroyed with explosives by the Libyan leader Colonel Gaddafi who saw it as symbol of Italian colonialism).

The next day the Brigade Liaison Officer, Lieutenant Alington brought a message from 8th Army instructing the brigade to move with maximum speed to Medenine in Tunisia. Speed was at once increased to 20 miles per hour and halts were cut down.

By the morning of 28th February 201st Brigade had reached Tripoli and was now officially part of the 8th Army. The battalions were reorganised and renamed as lorried infantry battalions. The machine gun platoons in each motor company were turned into motor platoons, and three Bren gun carriers from each scout platoon were withdrawn and their personnel transferred to motor platoons to increase rifle strength. That day the advance party left to reconnoitre the forward positions on the front line.

The Afrika Korps had been driven back through Egypt and Libya into Tunisia where they halted and made a stand on the Mareth Line, a system of fortifications built by France in southern Tunisia in the late 1930s. A natural bottleneck, the defensive line was originally intended to protect Tunisia against an Italian invasion from its colony in Libya. The line occupied a point where the coastal and southern routes into Tunisia converged, leading toward Mareth with the Mediterranean Sea to the east and mountains and a sand sea to the west.

In November 1942 a US–Anglo Force landed in Algeria and Morocco in Operation Torch, along with the French they drove eastwards to Tunisia to catch the Axis Forces of Germany and Italy in a pincer movement between themselves and Montgomery’s 8th Army who were driving westwards through Libya.

However the newly arrived Allied troops were to suffer at the hands of the battle hardened Afrika Korps. In particular the inexperienced Americans, who were routed in the Kasserine Pass, losing over a hundred tanks and being driven back fifty miles. A confident Rommel then turned west to face the 8th Army and planned an assault from the Mareth Line. However the Allies were forewarned by the Ultra code-breakers at Bletchley Park in Buckinghamshire and were expecting the attack.

Battle of Medenine

At 0300 hours on the morning of the 1st of March the brigade moved over the border into Tunisia, to a marshalling area west of Ben Gardene. Two days later the three battalions drove fifty miles to the west where they formed a defensive line on a circle on a circle of rocky hills known as the Djebel Tadjera, which rose abruptly from the plain. The huge convoy consisting of hundreds of vehicles and thousands of men, had motored over 2,000 miles from Qatana in Syria to the front line in Tunisia in just twenty three days.

The Scots and Coldstream Guards formed an anti-tank defensive position across the main Medenine to Mareth road. After digging in and camouflaging over sixty of the battalion’s vehicles, the Grenadiers dug their slit trenches covering the Tripoli to Gabes coastal road to the west of the other two battalions.

On 4 March the battalion came under air attack and three bombs were dropped in the battalion area. Guardsman Hunt of No 2 Company was badly wounded and later died of his wounds, becoming the first fatality from enemy action that the battalion had suffered during World War Two.

The expected German attack came at dawn on the 6th with the brunt of the fighting directed against the Coldstreams and Scots Guards positions, whose 6lb anti-tank guns knocked out sixteen panzers. Artillery accounted for another seventeen and neighbouring brigades brought the total of enemy tanks destroyed to fifty two, forcing the Germans to withdraw back to the Mareth Line. The Guardsmen suffered intermittent shelling and air attacks all day but the expected counter attack didn’t materialise.

On the 8th of March General Montgomery (GOC 8th Army) accompanied by Lieutenant Col Archer Clive visited 6th Battalion in a turret less Stuart tank named ‘Audax’. He was introduced to the officers and then addressed the men.

General Montgomery and Lt. Col. Archer Clive visit 6th Bn Grenadier Guards in Audax

The Grenadiers suffered further casualties on the 11th when Lieutenant H.J. Tufnell and Lieutenant B.J.D. Brooke were blown up and killed by a mine while out on a reconnaissance patrol in a jeep. The dangerous task of recovering the bodies was undertaken by Lieutenant Lord Brabourne along with some volunteers. Lieutenant Tufnell had only rejoined the battalion a few days previously from sick leave in Egypt. He was so determined to rejoin his unit that he lorry hopped on 22 vehicles and hitched a ride on a RAF cargo aircraft.

At 1900 hours on the 13th March the battalion moved forward and took over a position from the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders, from the 51st Highland Division. That evening John was part of a sixteen strong standing patrol led by Lieutenant J.K.W Sloan. Under the cover of darkness they moved forward of the front line, their task being to watch and listen on likely enemy approaches, gain information and prevent or disrupt enemy infiltration.

The battalion war diary records that at 05:45 hours the following morning the patrol was attacked by the Germans under the cover of a box barrage. Lieutenant Sloan and three others managed to get away, several were killed and the remainder, including John were captured. Fate might have saved him that night because a few days later the battalion was to suffer grievous losses in combat.

Battle of the Horse Shoe

On the night of 16th March the battalion, as part of a diversionary tactic by General Montgomery, was ordered to attack a formidable and prepared position known as the ‘Horse Shoe’. The attack was carried out by moonlight across a deep wadi, two successive minefields, and against a strongly entrenched enemy, mainly the battle hardened 90th Light Division of the Afrika Korps.

All objectives were reached but unknown to the battalion, surprise had been lost by the capture of an Artillery officer of the Highland Brigade who was carrying a marked map. On it were marked the successive lines of the intended artillery barrage, with timings, information that was of vital importance to the enemy. The General Staff was aware of the security breach, but as the attack was diversionary decided to go ahead with the operation.

The incoming German artillery barrage and the immense number of closely laid land mines resulted in very heavy casualties and prevented support weapons reaching the forward positions during the night. Without these, effective defence against counter-attack became impossible.

The battalion was ordered to withdraw at first light. Of the twenty nine officers who went into battle fourteen were killed, five were wounded, including the Commanding Officer Lt. Col. Clive, and five taken prisoner of whom two were wounded. Sixty three other ranks were killed, eighty eight wounded, and a hundred and four taken prisoner, of whom the majority were wounded. The dead included Lieutenant J.K.W Sloan, John’s platoon commander, who had escaped from the skirmish with the Germans the night that John was captured.

Lt. John Knox Walker Sloan, John's platoon leader. Killed in action 17 March 1943 during the Battle of the Horseshoe.

The Chaplain, Captain Worrall Reginald Leadbetter led a party of men into the minefield that had cost the battalion so many casualties. A total of 720 mines were lifted in order to recover sixty nine bodies. Revd. Leadbetter was later awarded the Military Cross for bravery. The battalion was re-formed into three weak companies under the handful of officers who had survived unhurt, but was not engaged in another serious battle during the remainder of the Tunisian campaign.

On 19 March 'Operation Pugilist' was launched against the Mareth Line. On the 26th 'Operation Supercharge II' commenced. The result was the outflanking of the Axis Line by the New Zealand Corps who reached El Hamma, forcing the Germans to withdraw from the Mareth Line.

On May 7, 1943, the British 7th Armoured Division captured Tunis, the capital of Tunisia, and the US II Army Corps captured Bizerte, the last remaining port in Axis hands. Six days later, on May 13, 1943, the Axis forces in North Africa, having sustained 40,000 casualties in Tunisia alone, surrendered; 267,000 German and Italian soldiers became prisoners of war.

The Allied victory in North Africa was critically important to the course of the war. Allied troops destroyed or neutralized nearly 900,000 German and Italian troops, opened a second front against the Axis, and permitted the invasion of Sicily and the Italian mainland in the summer of 1943. It also removed the Axis threat to the oilfields of the Middle East and to British supply lines through the Suez Canal to Asia and East Africa.

Prisoner of War

After his capture on the Mareth Line John along with hundreds of other prisoners was held in a transit camp in Tunis before being moved to the Italian mainland. Empty cargo ships that had unloaded their supplies in the port were used to transport the prisoners back to Naples. This was a perilous journey as over 2,000 Allied servicemen, locked in the holds of ships, perished in the Mediterranean after being torpedoed by British submarines.

Lieutenant Tony Davies of the Royal Artillery sailed the 250 mile voyage from Tunis to Naples in a former coal ship of around 2,000 tons. His account describes the dire conditions on board with buckets lowered into the bitterly cold, dark, damp hold to be used as makeshift latrines, much to the distress of the ones suffering from dysentery.

The only food was a little ship’s biscuit moistened with water. By comparison most captured officers, who were seen as important prisoners and treated differently by the terms of the Geneva Convention were flown back to Italy or in some cases transported by submarine.

John had been officially listed as missing in action for forty five days but on 28 April 1943 word finally arrived at the War Office, via the Italian authorities and International Red Cross that he was now a PoW.

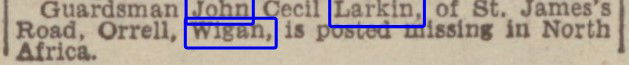

Missing in action list, Liverpool Echo 22 April 1943

Prisoner of War list Evening Express Saturday 8 May 1943

John's mother Catherine duly received a telegram from the War Office informing her that her son was now officially a prisoner of war. On 17 May 1943 the wife of John’s commanding officer, Mrs Penelope Clive wrote to Catherine from her London home, 181 Dorset House, Gloucester Place, NW1.

Dear Mrs Larkin

I feel I must write and rejoice with you over the glad news that your son is now known to be a prisoner, and I am so very happy for you. It has been a dreadful and anxious time and my thoughts and sympathy have so much been with you and all the 6th Bn families who have been anxious for their dear ones. However it must be a comfort to you now, to know that your son will be comparatively safe for the rest of the war, and that he will have many comrades with him to keep him company.

My husband will also be delighted to hear that your son is safe as he was heartbroken over the lives of so many of his beloved men, all of whom he was justifiably proud. He himself was wounded but is fit again and enjoined the Bn just in time to lead it on their final march to Tunis.

The news is certainly cheering and I do hope you will soon have your son returned to you. Please send him my best wishes when you write to him and I hope it will not have long to wait for a letter for him.

Yours sincerely

Penelope Clive

Mrs Penelope Clive

Captive in Italy

PoW’s from North Africa were initially held in Campo per Prigionieri di Guerra No.66. (Prisoner of War Camp No. 66 or simply PG 66) a transit camp at Capua, just north of Naples. With the defeat of the Axis Forces in North Africa it became clear that an invasion of the Italian mainland was likely. As a precaution the camps in southern Italy were closed and most of the inmates moved to prisons in central and northern Italy.

From Naples John was in a batch of prisoners transported north to PG 78 Sulmona, seventy five miles east of Rome. The camp was located in the tiny hamlet of Fonte d’ Amore, three miles north of the town of Sulmona, which lies in the Peligna Valley in the shadow of the Morrone mountains.

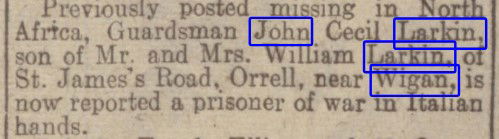

The front gates of PG 78 Sulmona

On 9 April 1943 John was transferred to PG 82 Laterina in the Province of Arezzo, 150 miles to the north west. The camp was located south of the little Tuscan town of Laterina on the flood plain of the River Arno. Construction of the camp had started in July 1942 and the first batch of prisoners arrived a few weeks later on 1 August.

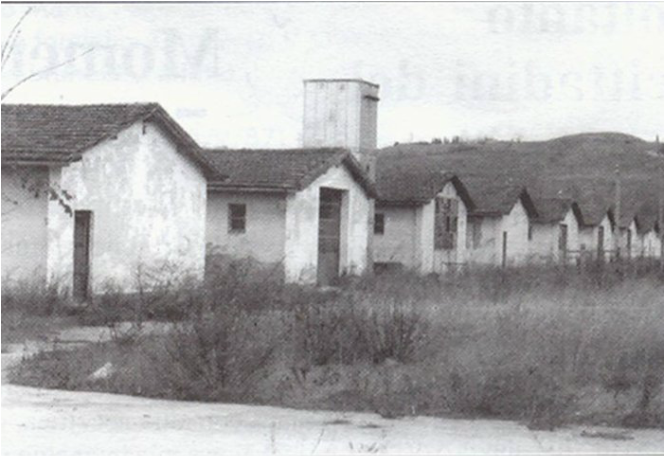

Post war photo of prisoner barracks in PG 82 Laterina

One of the first detainees at PG 82 was Gunner Frank Unwin of the Royal Artillery who had been captured at Tobruk in June 1942. He was amongst 2,000 prisoners who had disembarked at Brindisi and transported by train to Laterina in early August 1942. He told his story in his book ‘Beyond the Barbed Wire Fence’.

‘‘At that time accommodation consisted of tents and a brick kitchen. There were about 150 tents measuring 4 metres by ten metres with 18 men per tent. A South African Sergeant-Major was selected as camp leader.

The normal daily ration consisted of 120 grammes of bread, 120 grammes of pasta, and twice a week, a small portion of meat, and on two other days a small piece of cheese. A large open space between the tents and the kitchen was used for the daily roll call and was also used as a football pitch.

An Italian contractor brought in some Italian workmen – carpenters and electricians. POW’s provided manual labour. Eleven huts were built to house 250 men. At the end of each there was a wash-room and lavatory but were never supplied with electricity or water.

It became necessary to dig cesspits, ten metres long, a metre deep and one and a half metres in width. A twelfth hut eventually built for barber's shop and a store. Officials had their own hut as did the commander. There was a tent for concerts and shows. Pastimes included walking the perimeter fence, card games, football. International matches held between the five nations – England Scotland Wales, Ireland and South Africa.

Red Cross parcels contained about five kilos of food and fifty cigarettes. Families are allowed to send parcel once every three months which could only contain clothing, books and chocolate”.

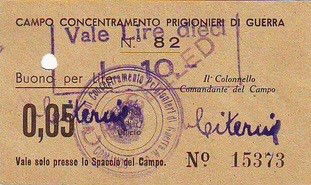

Camp coupon from PG 82 Laterina bearing the signature of the Commandant Colonel Citerni

The daily lives of prisoners of war in WW2 was regulated by the articles of the 2nd Geneva Convention of 1929. All the belligerent countries nominated a neutral country to act as a protecting power to look after the interests of their prisoners of war. Initially the United States of America had the responsibility of being the United Kingdom’s protecting power. But following their entry into the war after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbour in December 1941 the mandate was handed to Switzerland.

The Swiss Legation inspected prisoner of war camps belonging to the Axis Powers, sending reports to the International Red Cross which were then passed on to the countries from which the prisoners originated.

Report by the Swiss Legation

Captain Leonardo Trippi, Attache at the Swiss Legation in Rome visited Laterina on 26 May 1943, a few weeks after John’s arrival and made an official report on conditions in the camp. The report described prison numbers, camp installations, food and supplies, sanitary arrangements, medical services, complaints and discipline etc.

The leader of the NCO prisoners, known as the ‘Man of Confidence’, was Regimental Sergeant Major Andrew Samuel of the East Yorkshire Regiment. He represented the prisoners on any issues relating to their incarceration and camp conditions and worked closely with the Camp Commandant, sixty two year old Carabinieri officer, Colonello Teodorico Citerni.

The Senior British Officer (SBO) discharged the same role in the officers compound. The Man of Confidence and the SBO were issued copies of the Geneva Convention and were knowledgeable on the relevant articles concerning the treatment of prisoners of war.

Of the 3,080 registered inmates, 365 men were in a variety of work camps, doing agricultural work on farms or labouring in factories in seven different and widely separated locations. Thirty two were in the camp infirmary, fifteen in three hospitals in Arezzo, 179 in Military Hospital No.202 in Lucca, including 31 of various nationalities, most of whom had never been held in PG 82 previously even though they appeared in the prisoner rolls.

The second section of the camp had been completed but was not occupied, in the first section there were officers' quarters, shower-baths and dressing rooms, water closets, laundries, an isolation ward, an infirmary and a camp shop. A day-room was under construction as well as workshops for cobblers and tailors.

A water tank was placed in an elevated position but was not yet connected to the camp water supply, but this problem had been temporary alleviated by the installation of an electric pump which pumped water directly from the nearby river Arno through a pipe to the camp. There were still some problems however with the power supply, the electrical installation has been completed but was unable to be operated as parts of the trunk-line and switchboard were missing.

A structure holding forty Turkish water-closets (also known as squat toilets, basically a hole in the floor over which the user squatted) had been completed and taken into use. The water closets in the barracks for use during the night, has been installed but required connecting.

To serve the medical and spiritual needs of the prisoners there were two Italian doctors, three PoW doctors, Major Whyte, Major Ochse (South African), and Captain Barber, assisted by four medical orderlies, and also a dentist. There were two chaplains, Anglican clergyman Captain Maund, and a Roman Catholic priest, Captain W. Sheely who looked after a flock of about 300 Roman Catholics, including John.

Catholic Padre at PG 82 Laterina, New Zealander Captain William Sheeley.

The sick quarters were located in a wooden barrack. An isolation ward, located in a stone-built structure, contained three rooms, a washbasin and water-closet. There were twenty two patients in the sickroom, some with malaria, others with throat trouble and slight injuries. Nobody was confined to the isolation ward.

The Swiss Legation also visited the prisoners of war detained in three Italian hospitals, including Campo H202 at Lucca.. In one hospital six prisoners were confined to a large room. In another hospital there were seven detained prisoners of war. Some were suffering from chronic bronchitis, others from nephritis. A South African prisoner was recovering from an abdominal operation. During their inspection a prisoner was brought in from the camp with an inflammation of the lungs.

Three prisoners of war were confined to the isolation ward in the Ospedale Civico (Civil Hospital). Two of them with confirmed diphtheria, the third being a suspected case and under observation. Thirty one prisoners had been recommended for repatriation back home on medical grounds and were awaiting examination by the Mixed Medical Commission.

Twelve prisoners were under arrest for minor offences and insubordination. Two had attempted an escape but had soon be recaptured and were currently serving a punishment of 30 days in custody.

The camp shop, installed in a stone building was stocked with articles of common use, foodstuffs were not on sale. Ten per cent was added to the prime cost of these articles and the profits thus obtained were used for the benefit of the prisoners, to pay such expenses as otherwise would be debited to their account. A free issue of cigarettes took place every week.

Letters and parcels arrived in a good condition but complaints had been made about outgoing mail An adequate number of Red Cross parcels arrived regularly; the inmates of the camp were satisfied with the distribution as every prisoner of war was issued a parcel per week, of which he could dispose of freely.

A consignment of clothing of various sizes had recently arrived which included greatcoats, underwear, 900 pairs of boots and 200 pairs of socks.

The men who worked in the labour detachments were paid 4 Lira 50 cents per day; those employed in the camp as barbers, tailors, cobblers etc. received 3 Lire 60 cents per day. The officers often went out for walks; the non-commissioned officers were taken out on Sunday afternoons in batches of forty men. No walks had been organised for the men, the Commandant promised to have the men taken out as well..

All round the barracks were large rows of vegetable beds where the prisoners grew their own vegetables. A room in the new building had been appropriated for a library which for the moment contained only about 400 books; the Legation requested the Red Cross to send some more reading material. For entertainment the orchestra played every Sunday in front of the recreation tent.

Account of PoW Life by Pte Fred Hirst

Another PoW at Laterina was Fred Hirst who had been serving with the 2/5th Battalion Sherwood Foresters in Tunisia when he was captured by the Germans at roughly the same time as John. He wrote an account of PoW life in PG 82 in his book ‘A Green Hill Far Away’, extracts of which also appeared on the ‘WW2 Peoples War’ website:

“The camp was organised into huts about 40 yards long and eight yards wide. The bunk beds were in blocks of nine, that is three on the top, three in the middle and three on the bottom. All one structure. Life in the camp seemed to be largely one of tedium coping with a fair degree of physical discomfort, the ubiquitous lice and coping on very limited rations. The food supplies were greatly enhanced by the prized Red Cross parcels – each man got one parcel per week.

The parcels were oblong cardboard boxes weighing approximately 10 lbs, containing various tinned foods i.e. a 2 oz packet of tea, a 2oz packet of sugar and a tin of condensed milk, with 20 cigarettes and a tablet of soap in each. The tinned foods, previously mentioned were usually made up of a 2oz round tin of cheese, one standard sized tin of stewed steak or similar, a small tinned sweet pudding, an 8oz tin of hard biscuits, a tin of jam, a small tin of margarine, a tin of fruit, a tin of diced carrots and also included was a 4oz block of chocolate.

The Red Cross parcels were a vital supplement to the poor rations provided by the Italians consisting of ladles of ‘stodge’ containing various unidentified green vegetables with sometimes a little meat – again of unknown origin. This was issued twice a day. Two or three times a week bread buns were also issued and cheese once or twice a week which was cut into one ounce portions. There was a rigid rota system for ‘first choice’ to ensure everyone got a fair share.

A camp market developed where cigarettes were exchanged for various food items. This operated a bit like the stock market with the rate of exchange varying according to changing levels of supply and demand. Some of the men became experts at playing the market and would take their entire food parcel and offer its parts for cigarettes, then exchange those cigarettes for the food items which they preferred……If there was an arrival of some individual personal parcels from home containing cigarettes the prices on the market could fall….. The clever ones in the camp would get wind of such events and play their hunches according to the intelligence gained……Runners would dash into huts yelling ‘A tin of cheese has just exchanged for four cigarettes, down by two!’ or conversely ‘They are now wanting 20 fags for a tin of jam sponge, that’s five up on yesterday!’…Being a rather cautious type I usually kept what I had got and did not dabble in the business of the market.”

Allied Invasion of Sicily and Italy

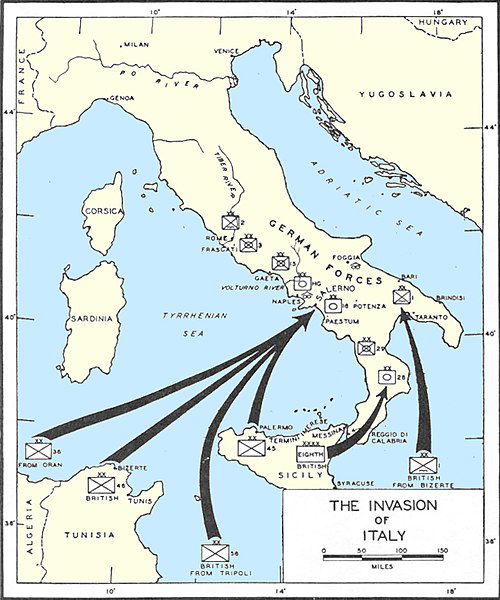

After victory over the Axis Forces in North Africa, Allied troops invaded Sicily on 9/10 July 1943 in Operation Husky. On 3 September, the Allies crossed the Messina Straits from Sicily and landed at Reggio di Calabria and Taranto on the toe of Italy.

The same day the Italian government surrendered and signed the Armistice at Camp Fairfield in the Sicilian town of Cassibile. The signing was kept secret and only announced to the media on 8 September. The next day the Allies launched Operation Avalanche, a seaborne invasion at Salerno, south of Sorrento on the Amalfi coast.

Operation Avalanche, the invasion of Italy.

In the invasion force was 201st Guards Brigade, now part of the 56th (London) Division which was attached to the U.S 5th Army under the command of General Mark Clark. John’s old unit, 6th Battalion Grenadier Guards was part of the second wave to hit the beaches. They were the first Grenadier battalion to set foot on European soil since the withdrawal from Dunkirk three years earlier.

From Salerno the Guards brigade fought their way up the mountainous spine of Italy. On 8 November they were in action on Monte Camino (nicknamed Murder Mountain), for four days and suffered greatly. When on 12 November 1943 the Battalion moved down from the mountain they had only 260 men fit for duty. They were never committed to a major battle again although they continued in action on the River Garigliano and at Minturno. The battalion was finally disbanded on 6 December 1944, after four years of existence.

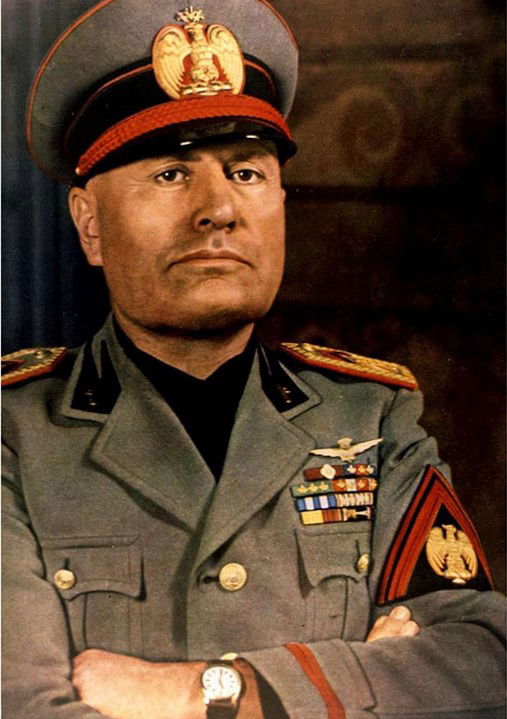

The Fate of Benito Mussolini

Following the Allied invasion of Sicily in July 1943, the Italian dictator Benito Mussolini (known as II Duce) was deposed and put under arrest in Rome; he was replaced by Marshal Pietro Badoglio who became the new Prime Minister. Aware that the Germans would likely try and liberate Mussolini in order to rally Fascist support he was moved in secrecy several times.

Benito Mussolini - IL Duce

From 28 August he was held in the Hotel Campo Imperatore, high in the mountains of the Gran Sasso d’ Italia Massif and guarded by 200 Italian soldiers. On 12 September Mussolini was rescued by two companies of Fallschirmjäger (paratroopers), accompanied by sixteen special forces troopers from the SS Lehrbatallion, under the command of Obersturmbannfuhrer Otto Skorzeny of the Waffen SS. Mussolini was then flown to Hitler’s headquarters, known as the ‘Wolf’s Lair’ near Rastenburg in Poland. Hitler installed him as leader of the Italian Social Republic, a German puppet state set up in northern Italy and based at the town of Salo near Lake Garda.

By 1944, the ‘Salo Republic’, as it came to be called, was threatened not only by the Allies advancing from the south but also internally by Italian anti-fascist partisans, in a brutal conflict that was to become known as the Italian Civil War. Slowly fighting their way up the Italian Peninsula, the Allies took Rome and then Florence in the summer of 1944 and later that year they began advancing into northern Italy. With the Spring 1945 offensive in Italy bringing a final collapse of the German army's Gothic Line in April, the Salo Republic was doomed.

On 25 April 1945 Mussolini fled Milan where he had been based, and headed towards the Swiss border with his mistress, Claretta Petacci. The pair were captured on 27 April by local partisans near the village of Dongo on Lake Como, and were executed the following afternoon, two days before the suicide of Adolf Hitler.

The bodies of Mussolini and Petacci were taken to Milan and hung upside down from a metal girder above a service station on the Piazzale Loreto square. Mussolini was buried in an unmarked grave, but, in 1946, his remains was dug up and stolen by fascist supporters. Four months later his body was recovered by the authorities who then kept it hidden for the next eleven years. Eventually, in 1957, his remains were allowed to be interred in the Mussolini family crypt in his home town of Predappio, to the north west of San Marino in northern Italy.

PoW Stand Fast Order

In June 1943, MI9 or Military Intelligence, Section 9, a British secret service agency that helped Allied and airmen evade capture and return home issued the notorious Order P/W 87190. It instructed prisoners of war in Italy to stay put in the prison camps and wait for Allied forces to arrive and liberate them. It read:

‘In the event of an Allied invasion of Italy Officers commanding prison camps will ensure that prisoners of war remain within camp. Authority is granted to all Officers Commanding to take necessary disciplinary action to prevent individual prisoners of war attempting to join their own units.’

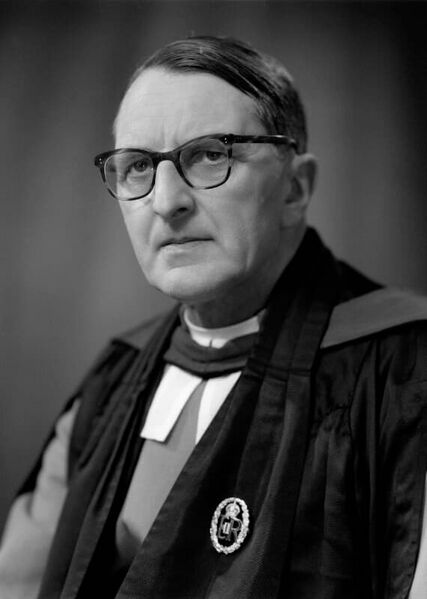

The order was issued through the popular radio programme ‘The Radio Padre’. a weekly talk every Wednesday evening at 7pm by the Reverend Ronald Selby Wright, previously Chaplain to the 7th /9th Royal Scots regiment. He began the show, ‘Good evening, forces.’ His use of the word ‘forces’ being the sign to PoW's listening in on their clandestine radios that there was a hidden message further on in the broadcast.

The Radio Padre, Revd. Ronald Selby Wright

The General Staff wanted to avoid thousands of PoW’s roaming the countryside that might impede the Allied advance, as it believed that Italy would soon be out of the war and that Germany would withdraw its forces north into Austria. Instead the Germans did exactly the opposite and flooded Italy with reinforcements down through the Brenner Pass from the Austrian city of Innsbruck

At the time of the Italian Armistice on 3 September 1943 there was an estimated 80,000 Allied PoW’s in the camps, including 42,194 British. Three days later the Badoglio Government instructed camp commanders to release the prisoners. Many did so, but were arrested by the Germans for this action, some being sent to prison camps in Greater Germany. After the Italian guards deserted the camps there was a window of opportunity when the prisoners could simply walk out unhindered. Approximately 50,000 did exactly that and escaped into the countryside. The Germans quickly reacted to the order from the Italian government and took control of the camps. They rounded up thousands of PoW’s and transported them to Germany in cattle trucks. It is estimated that over 2,000 of these prisoners died in captivity.

Some Senior British Officers (SBO’s) in charge of the prisoners thought that the stay put order was out of date owing to the changed military situation and left it up to individuals if they wanted to abscond or stay in the camp. Other SBO’s stuck rigidly to the order, posted their own men in the empty watch towers and threatened to Court Marshall anyone who attempted to escape. This happened at PG 57 Trieste and at PG 21 Chieti when German Fallschirmjäger arrived at the camp gates and were astonished to find all the prisoners still in the camp unattended.

An estimated 50,000 prisoners escaped, many headed south on the dangerous journey to cross the Allied lines to freedom. Some from the northern camps opted to attempt the shorter journey over the Alps to neutral Switzerland. Here they were interned for the duration of the war. Their only option was to cross the frontier into France, contact the Resistance and travel via the escape line over the Pyrenees to Spain and onto Gibraltar.

Many thousands were recaptured, some dying in PoW camps in Germany and Poland. Some joined partisan groups who provided food and shelter in exchange for their military expertise, others took refuge on small farms aided by friendly peasants. An unknown number were shot by the Germans and Fascists or perished in the severe winter in the mountains.

Since the end of WW2 speculation on the origin of the stand fast order has intrigued historians. Some say the order came from Scots Guardsman Major Norman Crockatt, the head of MI9, others that it was General Montgomery or even Prime Minister Winston Churchill. Since the original order has since disappeared from the records in the National Archives at Kew its source will remain a mystery.

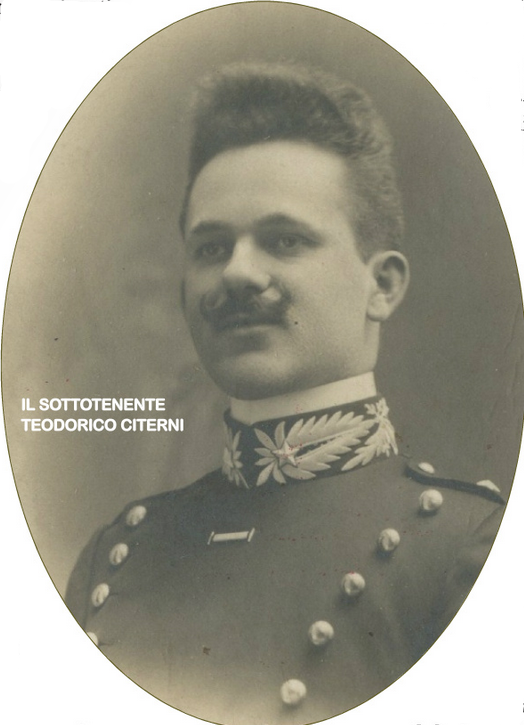

The Trial of Camp Commandant Citerni

The Camp Commander at PG 82 Laterina, Colonel Teodorico Citerni was born into a noble family in Scalino near Grosseto in 1881. He passed into history with the name of ‘Lion of Gunugadu’ for his heroic actions during the Fascist East African Campaign in October 1935, for which he was awarded the silver medal for military valour. Colonel Citerni served in the Carabinieri, the Italian Military Police, although regulated by the Ministry of Defence it was also responsible for enforcing civilian law.

Teodorico Citerni as a young Second Lieutenant in the Carabinieri

Following the Italian Armistice in September 1943, he was arrested by the Germans for not having handed over Camp PG 82. He was imprisoned in the Regina Coeli prison in Rome from which he subsequently escaped. During his period in Rome he was commander of the 'Banda Manfredi', a small resistance group of about 20 ex-army officials named after a Lieutenant Colonel in the Carabinieri. who had joined the resistance movement from the Fascist Military Information Service.

The 'Banda Manfredi' was itself part of a larger group known as the ‘Fronte Militare Clandestino ‘which had been organised by nobleman Giuseppe Cordero Lanza di Montezemolo, to bring about a peaceful transition from German to Allied occupation of the city, thereby ensuring that it was not taken over by communist factions.

Commandant Citerni was arrested by the Allies for alleged war crimes and held in Transit Camp No.3 before being tried on 1 August 1946. The War Crimes Tribunal found that he was not guilty of any war crimes and as he had already served six months in custody he was sentenced to a nominal one days imprisonment and released. Citerni died in 1975, aged 94.

Escape and Evasion

Several escape tunnels were attempted at PG 82 Laterina and one constructed from hut 6 to beyond the perimeter fence was just operational when the Armistice was declared on 8 September 1943. On the morning of the 12th the guards deserted their posts. From Italian records it is estimated that 2,720 prisoners escaped from the camp before the Germans arrived later that day.

Roughly the same number obeyed the stay put order and remained. They were rounded up by the Germans and sent first to PG19 Bologna before being transported in cattle trucks to Stalag XIIA at Limburg an der Lahn, near Frankfurt. The conditions at Limburg were bad, as it only functioned as a transit camp processing newly captured prisoners of war before distributing them amongst the other, better organized Stalags in Germany and Poland.

A week after the Armistice the Germans issued a decree to the Italian population warning that anyone who helped escaped British and American prisoners by providing food, shelter and clothing would face severe penalties. This included having their homes burnt down, deportation or execution. The first military decree of the new fascist republic on 10 October also made it a capital offence to aid and abet the enemy. A further proclamation on 23 September offered a reward of 1,800 Libras to anyone who recaptured a British or American escaped PoW and handed them over to the authorities.

The evaders soon learned to keep away from the large estates as the wealthy land owners tended to be owned by fascist sympathisers. As the weather turned colder they sought refuge during the winter months at the smaller farms instead, inhabited by poor tenant farmers, the Contadini, sleeping in haylofts, barns and caves.

Winston Churchill, himself a successful escapee from South Africa during the Boer War, wrote in his ‘History of the Second World War’:

‘Over 10,000 PoW's in German occupied Italy were fed, hidden and guided by the Italian people, often the poorest from the Italian countryside. Many were shot for this great spontaneous gesture of humanity’. There were many brave deeds carried out in Italy that have never been rewarded’.

In October 1945 Colonel Hugo de Burgh became head of the Allied Screening Commission (ASC) which had been set up to recognise and compensate civilians who had helped Allied evaders behind enemy lines after the Armistice. He was the former SBO at PG 49 Fontenallato and successfully escaped to Zermatt in Switzerland on 29 September 1943.

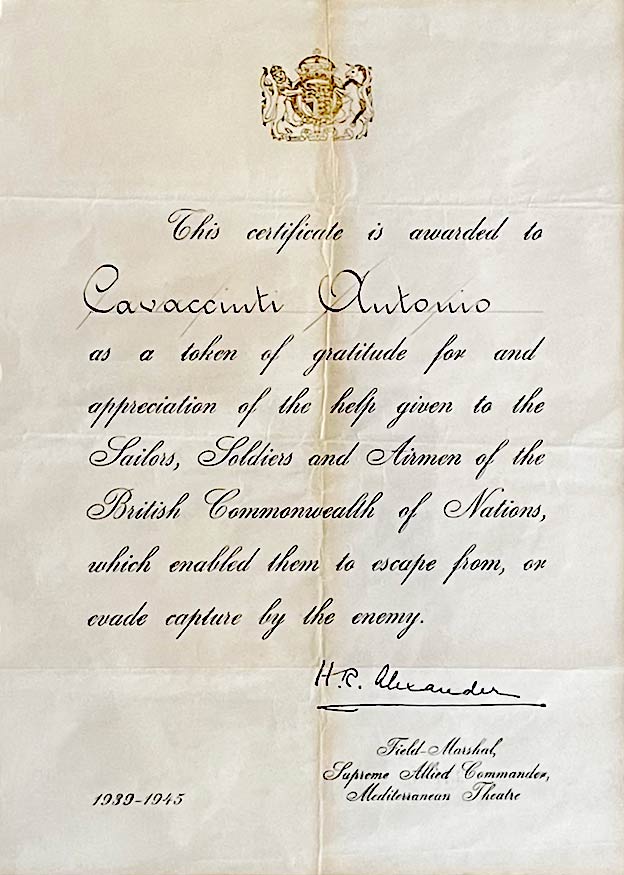

Alexander Certificate awarded to Cavaciuti Antonio

It was normal practice for PoW escapers to pass on their name and address to anyone who befriended them just in case any mishap befell them. Some officers wrote testimonials detailing the assistance received. This information later helped Italians with their claim for compensation. Over 75,000 ‘Alexander Certificates’ were awarded to Italian families, signed by General Sir Harold Alexander, the Commander in Chief of the Allied Forces in Italy, in recognition of their contribution in feeding, clothing, and sheltering Allied servicemen, despite the great risks involved.

Partisans

In Summer 1942 it was made mandatory for able bodied PoW’s of private and lance corporal rank to work as long as it was unrelated to the Italian war effort. Under the terms of the Geneva Convention officers were not permitted to work and remained in the main camps.

At the time of the Armistice John was employed at an unknown work camp, probably one of the PG 82 satellite camps, the Locatelli farm estate at Taverne d’ Arbia, a few miles east of Siena, and thirty miles south of Florence. After the Italian guards deserted their posts John and his comrades split into small groups and headed for the open countryside. Living on their wits they slowly made their way south towards the Allied Lines, travelling at night and hiding up in the day.

Through the freezing winter months of 1943 they obtained food and shelter from friendly peasants who bravely helped the evaders, despite the dangers entailed. In the Spring of 1944 John and some of his fellow PoW’s joined the partisan band that was active in the area around the small medieval walled town of Roccastrada. As its name implies the town lies on a rocky prominence between Florence to the north and Grosseto to the south.

Roccastrada, Province of Grosseto, Tuscany

The partisan movement, some 200,000 strong was a complicated and diverse coalition of political groups such as the Communists, Monarchists, the Catholic Christian Democracy, Socialists, Liberals, Republicans and Anarchists.. Although united in the fight against Nazi Germany and the puppet Fascist Social Republic they all harboured different political ambitions. But eventually they all came under the umbrella of the Committee of National Liberation (CLN),

The Communist Party groups with 50,000 members were fighting on three fronts: a civil war against Italian fascists, a war of national liberation against German occupation, and a class war against the ruling elites. At the same time there was friction and hostilities between rival groups.

The main activity of the partisans was road and rail closures, bridge destruction, power and phone line sabotage, abduction of political prisoners from prisons of the Italian militia, and raids on individual or small columns of vehicles and isolated garrisons.

German authorities repeatedly appealed to the Italian population not to support the partisan gangs, warning that the penalty for doing so was severe. They tried to alienate the population from the resistance by adopting a reprisal policy of killing ten Italians for every German killed by the partisans. Those executed would come from the village near where an attack took place and even from captive partisan fighters.

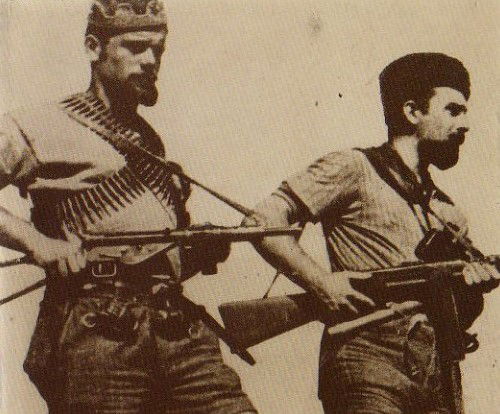

The partisan group operating in the Roccastrada area was a battalion belonging to the 2,000 strong communist Third Garibaldi Brigade ‘Antonio Gramsci’, named after the one time leader of the Italian Communist Party. The 400 strong unit wore a distinctive red handkerchief round their necks, a red star on their hats and hammer and sickle emblems.

Two Garibaldi partisans, the one on the left is carrying a British Sten Gun, the other a Beretta 38 MG.

The partisans insisted that the Allied soldiers live as Italians, only speak Italian and threatened that if they heard them speaking English they would shoot them.

At dusk on 18 May 1944 John was a member of a thirty strong raiding party of partisans and Allied escapers that attacked the town jail in Roccastrada, in a bid to rescue two British evaders who had been betrayed and arrested. Earlier the partisans had exacted revenge by killing a member of the fascist militia who was carrying out spying activities and also one of his informers who had infiltrated their organisation. During the assault on the prison the partisans killed the warder and a member of the fascist militia. The two evaders had been moved on but all the other prisoners in the jail were released. John mentions this incident later in a letter home to his mother. He wrote:

‘The only bad people I have met were the Fascists and they were really bad. For our capture they receive some kind of tin medal and a large amount of Jerry stamped Italian money. Only two months ago, two mates of mine were given over to the Jerries by these people but afterwards there were two less Fascists in the world. This sounds a bit bloodthirsty, but you will realise it is quite just when I tell you the whole story.’

Following the prison raid the Germans were quick to react, launching anti-partisan operations in the woods near Roccastrada that the fighters were using as a base. In March 1997, 53 years after the incident and triggered by events in Kosova that he had been watching on TV John put pen paper to record his memories. He wrote:

'We scooted back off to the depths of nearby woodlands. The following day all hell was let loose. All around us was the sound of small arms firing into the woods, fortunately they stuck to cart tracks. Towards the day’s end all went quiet. It was decided amongst us POW’s to break up into two’s or threes and got out of the area double quick.

I along with two others, one was an American (pilot), I remember him but not the other fellow, anyway we decided to go south aiming for Siena. Immediately it got dark we were on our way. (the passage of time had clouded John’s memory over the direction they fled as Siena was to the north and wasn’t liberated until July 1944 by the Free French forces).

I remember that night well, the urgency of getting quickly away was uppermost in our minds with little thought to proceeding carefully. So it was that we got the fright of our lives, such a racket broke out for a few moments we thought we had stumbled upon one of the patrols from the previous day. It turned out to be a herd of wild boars we had disturbed.

I often think back to those times, the English officer was a decent sort and I didn’t have to sir him. The partisans, well they were more for a skinful of vino than fighting. As for ourselves I remember my footwear was a pair of cut down welly boots. The whole incident was so funny in many ways, charging up to this town jail, with no preparation or thought of the consequences. We were lucky to have got away with it.

During our flight from the area of Roccastrada we came across this open space on a hill summit. The time would have been two or three o’clock in the afternoon. The field if it could be called that was about the size of two football pitches, and it was being ploughed. We approached the farmer and asked if he could spare us a drink and a bite to eat. He was quite friendly and invited us into the house. His two young children, they would be about six years old and well fed. But they were so black. The farmer explained that he had no running water, his only supply was about a mile or so down the hill.

During my time in the Middle East or since I have never seen such poverty, we just accepted a drink from him and then proceeded on our way. Seeing on TV the plight of the Kosova refugees, especially the very young and the old brought back memories of that farmer and his children.’

Captain Franco Tesi

Shortly after the jail incident though John became separated from his companions and continued his journey alone. At Monte Cucco, 14 miles south east of Roccastrada John met an Italian army officer, Capitano Franco Tesi. Travelling on foot and in civilian clothes, Franco who was an anti fascist was attempting to reach the Allied lines.

Captain Franco Tesi, Bersaglieri Regiment

(It is possible to piece together Captain Tesi’s story from his statement to the authorities shortly after his capture.)

By 15 September 1943, a week after the signing of the Instrument of Surrender the Germans disarmed over a million Italian soldiers in Italy, the Balkans, the Mediterranean region and Eastern Europe, killing 29,000 in the process.

At the time of the armistice Captain Tesi of the Bersaglieri Light Infantry regiment, (famous for the long black plumes worn on their head gear and running style of marching), was attached to the General Staff of the 51st (Siena) Division based on the Greek island of Crete. German troops soon occupied the island and imprisoned the Italian garrison. On 17 October 3,000 prisoners embarked on the 8,000 tonne ship ‘Siena’ bound for Athens, the vessel was carrying various war supplies including 1,000kilos of TNT and 2,000 aircraft bombs.

At about 10 pm on the night of the 19th October, and 45 miles from Crete the ship was torpedoed. About an hour later the stricken vessel was attacked again and set ablaze by two British aircraft. The German soldiers guarding the prisoners shot and machine-gunned Italian soldiers who tried to reach deck and escape.

After sixteen hours in the water, around 500 survivors were rescued and taken back to Channa on Crete. From here, starving, wounded, thirsty and naked, they were taken to the prison in Agia where they were met with insults, beaten with whips and threatened with firearms. They were denied food and clothing.

The Germans who now regarded the Italians as traitors instead of allies demanded that they declare if they wished to fight with the Germans, work for them or be imprisoned. The only way to freedom and repatriation was to swear an oath of allegiance to Adolf Hitler. Gradually more and more prisoners, driven by hunger did just that until there was only 17 left, including Captain Tesi.

On 17 November all but two senior officers decided to take the oath. Captain Tesi signed reluctantly but swore that when he got back to Italy he would either go into hiding, join the partisans or rejoin the Allies. His route back home was via Athens, Yugoslavia, Hungary, Germany and Austria, arriving in Verona in northern Italy on 26 December 1943. Here the Germans handed him over to the Fascist authorities who then transferred him to Macerata, 200 miles to the south.

On 9 February he was asked to swear an oath of allegiance to the new Fascist Republic, which he refused to do. After being placed under house arrest for seven days he was then put on unlimited leave pending a decision by the Ministry of the Armed Forces.

Captain Tesi decided he would join the partisan movement and contacted members of the Liberation Committee in Macerate who sent him to Turin to join the 700 strong group, which included 14 British escaped prisoners, led by Nicola Prospero, known as ‘Funso’. As an experienced soldier he was tasked along with a Captain Nasi in helping to organise the group into a fighting force. They found the group was ill equipped, short of weapons and equipment and were poorly trained.

However due to anti-partisan operations by the Germans in the neighbouring Lanzo valleys the ‘Nicola’ group found itself isolated. In early April they were surrounded by German and Republican troops ready for action. A truce was reached and Nicola was personally invited to Marshal Kesselrings' headquarters at Pinerolo, south east of Turin.

During the talks Marshal Kesselring asked Nicola to provide security in the Germans rear areas as they fought the threat to the south from the Allies. Nicola agreed but asked for and obtained the removal of all German and fascist forces from the Lanzo valleys and Canavese areas. He also asked for and obtained assurances of supplies of weapons, provisions, equipment, money and the possibility of recruitment. As part of the agreement he controversially agreed to hand over to the Germans the 14 British PoW’s who were fighting with his group.

Later Captain Tesi testified that Nicola had signed the agreement in order to protect the Nicola group from annihilation and his real intention was to release the British PoW’s and use the newly acquired weapons against the Germans. However the Communist partisans in the north saw it as an act of betrayal and shot and killed Nicola.

On 31 May Captain Tesi was recalled to the Political Office of Turin. He was told that an arrest warrant had been issued against him for not signing the oath of allegiance to the Republic. It had also been reported to the Prefecture of Turin that he was an anti-fascist element. Captain Tesi argued that he could not be anti-fascist as it had been established that he had signed an oath of allegiance to Adolf Hitler in Greece. Having been released under observation he decided that now was the time to leave Turin and make the 300 mile journey to the Allied lines.

Captain Franco Tesi, centre

On 3 June 1944 Captain Tesi set off from Turin on the long journey south, first by rail to Bologna, via Milan, then then by lorry to Florence where his home was. He remained there a week waiting for promised transport, which never arrived.

On the 13th he set off on a bicycle acquired by his wife Franca and cycled the 33 miles to Siena. From there he set off on foot reaching Monte Antico. On the 15th he continued on foot via Sasso d’ Ombrone to Monte Cucco. A small hamlet high in the hills overlooking agricultural land and vineyards.

The tree lined approach to Monte Cucco where John Larkin was destined to meet Franco Tesi.

Here the paths of Captain Tesi and John Larkin were to cross, after fleeing Roccastrada John became separated from his two companions and continued alone. In Monte Cucco he was detained by a group of partisans, who believing he was a German threatened to shoot him. Captain Tesi was able to vouch for his nationality and invited John to accompany him on the last leg of his journey.

At 8 am on 16 June 1944 he and Captain Tesi met a patrol from the American 36th Division in the newly liberated city of Grosseto. After six months as a prisoner of war and nine months as an evader behind enemy lines, and a month after fleeing Roccastrada John was once again a free man. It was exactly two years to the day since he had sailed from Liverpool with his battalion.

Repatriation

After interrogation by officers of the American Military Intelligence Service at Grosseto Captain Tesi was interrogated again at the headquarters of the American 5th Army in Civitavecchia. He then made his own way to Rome where he offered his services in an operational capacity to the Italian army. He was accepted and promoted to Major. On 21 April 1945 his battalion, along with American, Polish and Partisan forces was involved in the liberation of Bologna,

After his debrief in Grosseto John was moved to a repatriation camp in Naples before embarking for the UK by sea, arriving in Scotland on 11 August 1944. After an extended period of home leave he was posted back to Scotland to Stobs Infantry Training Camp near Hawick in the Scottish Borders. It was normal practice that escaped PoW’s were not sent abroad again for six months for security reasons, instead they were employed in training and administration duties.

On 27 November 1944 John attended a four week long motor cycle course at the Driver Maintenance School at Keswick in the Lake District. Taught by Royal Army Service Corps instructors they perfected their cross country skills over the nearby Skiddaw Mountain in all weathers. Later he was posted to Victoria Barracks in Windsor where he had been stationed three years earlier with the training battalion.

On 28 March 1946, after five years and four months of service in the Brigade of Guards John was released from the colours to Class W (T) Royal Army Reserve. This meant that he would receive no pay or emoluments from army funds and would not be called upon to wear uniform or be under any military discipline. However he remained liable to be recalled for military service at any time. For his war time service he was awarded the 1939-1945 Star, Africa Star with 8th Army clasp, and the Italy Star, which he received on 24 February 1950.

The marriage of John Cecil Larkin and Margaret Eileen Berry, 18 April 1949, St. James RC Church, Orrell

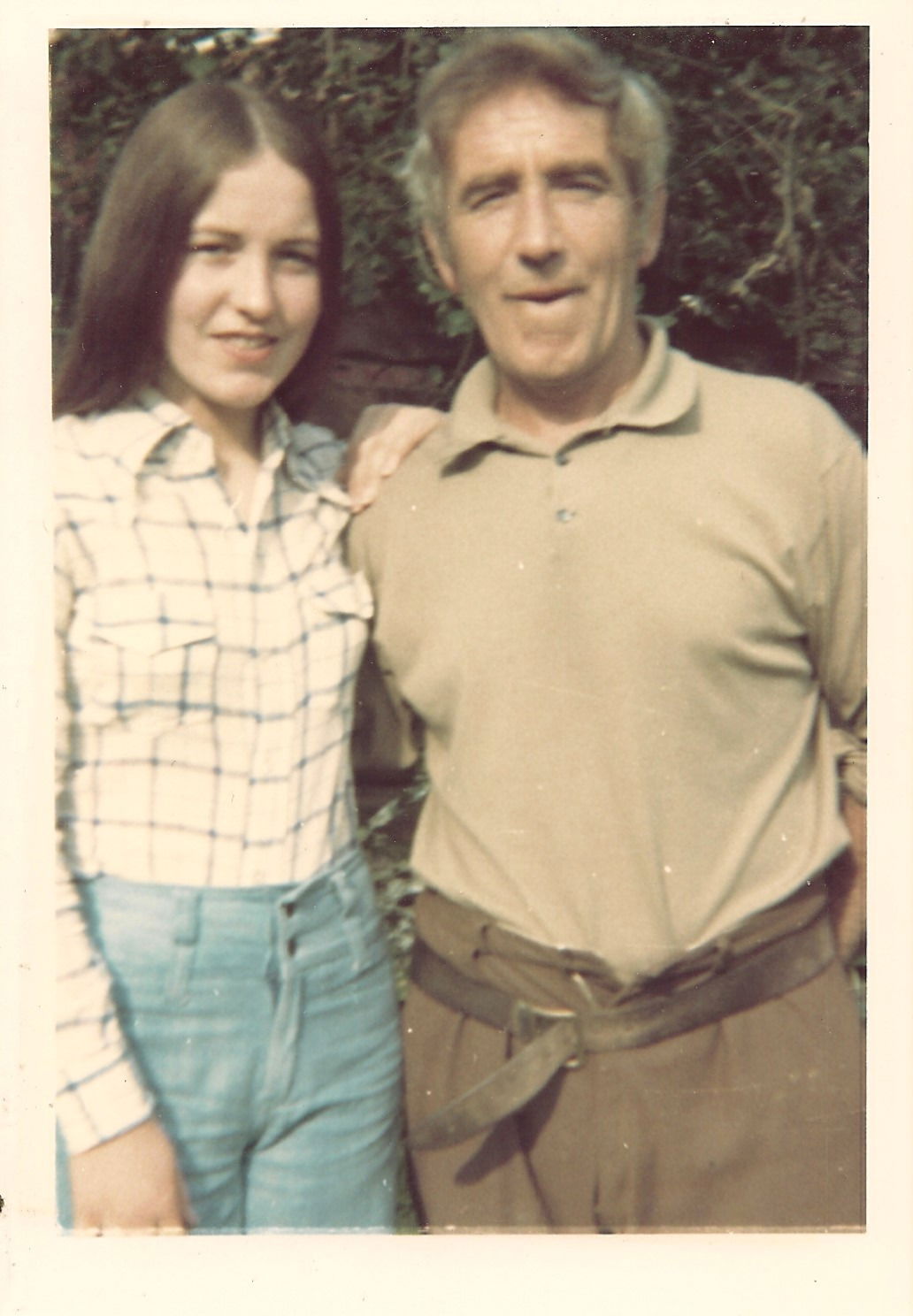

After demobilization John was employed in various occupations including as an operative at Pilkingtons glassworks in St. Helens, a weaver at a local silk mill, and for many years a scaffolder for Wigan Council. On 18 April 1949 he married Margaret Eileen Berry at St. James RC Chapel in Orrell. Their son John Andrew Larkin (known as Andrew) was born in 1950, followed by a daughter Barbara Christine Larkin in 1954.

John Larkin pictured with his daughter Barbara in the early 1970's.

Andrew reveals that, unbeknown to his family until towards the end of his life, his father suffered from Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), a mental health condition that wasn't formerly recognised until the 1980's. Servicemen and women of John's era came back from the Second World War without counseling and were just expected to pick up the threads of their civilian life and carry on. They carried the mental scars of war time traumas for the rest of their lives.

John Cecil Larkin died 19 October 2008 aged 88 and was buried at Our Lady & All Saints RC church in Lancaster Lane, Parbold.

The grave of Guardsman John Cecil Larkin, Our Lady & All Saints RC Church, Parbold

Andrew Larkin at the graveside of his father

There are many thousands of untold stories of bravery, perseverance, and fortitude just like John’s that have gone unrecorded, they have been lost forever in the mists of time. It is no understatement to say that the men and women who fought and endured during the Second World War belonged to the greatest generation.

Lest We Forget.

Graham Taylor 2025

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to writer and historian Janet Kinrade Dethick for her invaluable advice on Allied PoW’s in Italy and Italian PoW camps.

Thanks to Andrew Larkin, Olivia Blakeman, and Lorenzo Ferraro for providing information and photographs. Also to Globe Translations for the translation of Italian military documents

Main Sources

‘The Grenadier Guards in the War of 1939-1945 by Nigel Nicolson & Patrick Forbes v.2

Capitano Franco Tesi – statement 23 June 1944

www powcamp82laterina.weebly.com

www.campifascisti.it

Other Sources

Ancestry

Forces War Records

Britannica

Forces War Records

Fred Hirst - ‘A Green Hill Far Away’

Frank Unwin - ‘Beyond The Barbed Wire Fence’

Jonathan Forbes - The Battle of the Horseshoe’

Malcolm Tudor – ‘Paths to Freedom, Escape and Evasion in Wartime Italy’

Monte San Marino Trust National Archives

Roger Stanton – Italy 1943/1944

A Hard Slog - Second World War Experience Centre

Victoria Blake - The Scandal of MI9 and the Stay Put Order’

www nctuto.it.roccastrada-marzo.luglio.1944

Wikipedia

WW2 Peoples War

WW2 Talk