Haigh Moated Site, Old Haigh Hall and Bradshaigh Chapel.

INTRODUCTION

The purpose of this paper is to present evidence and critically analyse interpretations of the history of three important monuments in the Wigan area: Haigh moated site, Old Haigh Hall and the Bradshaigh (Crawford) Chapel in Wigan All Saints Parish Church.

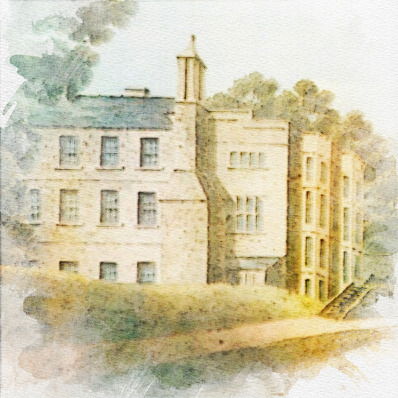

It is well recognized that the present Haigh Hall was built in 1827-c.1844 by James Lindsay, the 7th Earl of Balcarres (later Earl of Crawford), on the site of an older hall. There is good evidence that the Old Hall had sections dating from the 16th to the 19th centuries, with speculations about even older sections.

There is firm evidence of a moat and moat house a few hundred metres to the north of the present and old halls. The moated site is a Scheduled Ancient Monument.

Bradshaigh Chapel in Wigan Parish Church is attributed to the Bradshaigh family of Haigh Hall, but no vestige of the original chapel exists.

There are two intriguing questions related to these three important parts of Wigan history : a) was the moat house the first Haigh Manor House, and b) when were the moated site, the Old Hall, and Bradshaigh Chapel built and by whom?

As with much of history, there is a dearth of detailed evidence on which to answer questions in a definitive manner. The resulting uncertainty about their history leads to a variety of interpretations and speculations. Here I document what we know about the origins of these monuments. Documentary evidence provides the highest degree of confidence in establishing what we know about the past. When I say there is no documentary evidence, I mean that I have not found documentary evidence, not necessarily that it doesn’t exist. In the absence of documentary evidence, interpretation and speculation can provide insights into the past, but with lower levels of confidence.

THE MOAT HOUSE

Wigan Council states that “this site [The Moat House moated site at Haigh] consists of the moat of a now lost medieval manor house. The moat is completely dry and has been incorporated into the garden of the 19th century Moat House. Although no documentary evidence survives, the house probably stands on the site of the medieval house on the island in the centre of the moat. The house is grade II listed but excluded from the schedule, although the ground beneath is included. The house was built c.1840 by the Earl of Crawford and Balcarres for one of the land agents of his Haigh Estate. The moat is square in plan and with each side being 50 meters long. The sides are stone lined and on the north side the remains of a stone bridge survive beneath an outbuilding, which was probably the original approach to the medieval house”.

The 1776 Haigh Estate map shows a moat with a building on the central platform and a building just outside the moat. Fishponds are shown a short distance to the northwest of the moat. The entrance to the moated platform is on the south side.

The same moat, buildings and fishponds are shown on the 1849 Ordnance Survey (OS) map (Fig. 1). It is called a Moat House. The Moat House is to the west of Tanners Lane, which leads to Copperas Lane to the south. Again, the entrance is on the south side. Fig. 1. 1849 OS map, National Library of Scotland

Fig. 1. 1849 OS map, National Library of Scotland

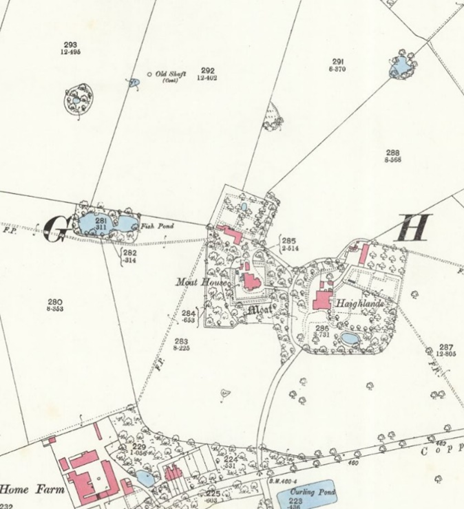

The 19th century changes described by Wigan Council are shown on the 1894 OS map (Fig. 2). The entrance is now on the north side.

Fig. 2, 1894 OS map (National Library of Scotland).

Fig. 2, 1894 OS map (National Library of Scotland).

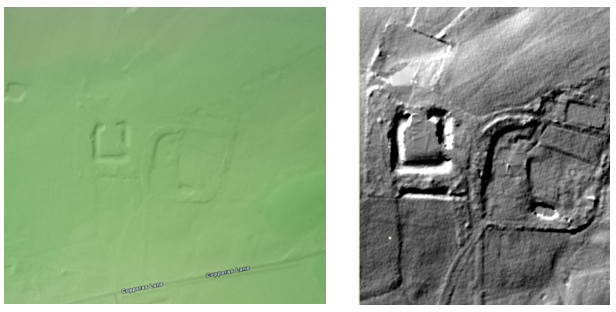

The moat can also be seen clearly in LIDAR photos (Figs. 3 and 4). LIDAR stands for Light Detection and Ranging and is a remote sensing method that uses light in the form of a pulsed laser to measure ranges (variable distances) to the Earth. These light pulses—combined with other data recorded by the airborne system — generate precise, three-dimensional information about the shape of the Earth and its surface characteristics, often penetrating through vegetation.

Figs. 3 and 4. LIDAR photos (ArcGIS) of Moated site and Haighlands at Haigh.

We can gain some understanding of the Haigh moated site from information on other moated sites in the area. There are about 40 moated sites in the Wigan area3,4. Many moated sites can be identified on 19th century OS maps, but most have been destroyed. As far as I know, none of the original buildings within the moated sites have survived, although some of the original materials are incorporated in later buildings.

Most moated sites served as prestigious aristocratic and manorial residences with the provision of a moat intended as a status symbol, rather than a practical military defense. Information on the landed gentry who built the moated sites and manor houses can be useful in understanding the moated sites. For the Haigh moated site the main families of interest are the le Norreys (Norris) and Bradshaighs (Bradshaws).

In addition to the Haigh moated sites, there are moated sites close by in Aspull (Bradshaw Hall, Gidlow Hall, Kirkless Hall, and Lower Highfield Manor House) and in Blackrod (Arley Hall). This quite dense cluster of moated sites reflects a complex of social and tenurial factors and it is not clear how many of the moat houses or halls were ‘manorial’.

There is no documentary evidence to identify the dates when the moated sites were first built, or who built them. As most moated sites in England were built in the period 1150 to 1350 it can be reasonably assumed that the Haigh moated site was built during this period.

The manors of Haigh, Blackrod and Westleigh were in the hands of the family of Le Norreys6. Blackrod had been granted by John Earl of Moreton, in the reign of his brother Richard I, to Hugh le Norreys. Donald Anderson5 states that Hugh Le Norreys is the earliest known Lord of Haigh in 1193. There is no documentary evidence for the location of a Haigh Hall at this time and no explanation of whether the reference to Haigh is to Haigh manor house, Haigh manor or Haigh Hall. We don’t know where Hugh lived, but as Lord of Haigh it is reasonable to assume that he lived in a manor house or hall.

Arthur7 states that Haigh Hall was held by the Le Norreys family for four generations, but does not specify the location of the Hall. In 1295 Haigh came into possession of Hugh’s granddaughter, Mabel, who married Sir William Bradshaigh.

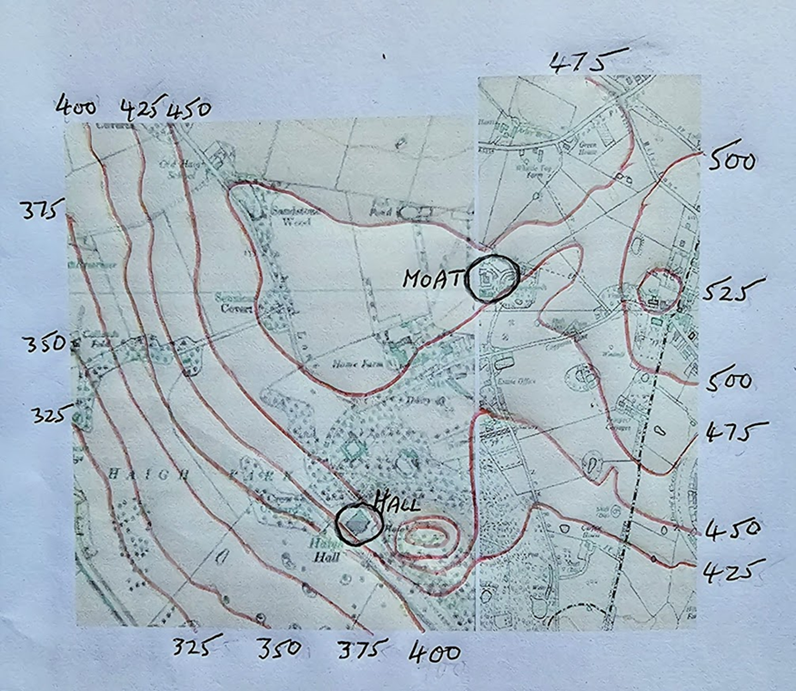

A relief map of Haigh (Fig. 5) shows the contours of the land and the locations of the moated site and Haigh Hall. The Haigh moated site is at a high elevation of about 480 feet and is about 50 feet higher than the hall at about 430 feet. Fairly flat sites for moats are common, but most moats in the Wigan area are at much lower elevation.

Fig. 5. Relief map of Haigh (feet), Derek Winstanley.

Fig. 5. Relief map of Haigh (feet), Derek Winstanley.

The moated site is on a high, flat “plateau” and would have given inhabitants magnificent views across the Pennines to the northeast and the Lancashire Plain to the west. The Old and New Halls are on platforms cut into a quite steep slope, which would not have been suitable for building a moat. The site of the Old and New Halls offers the halls impressive views from the southwest to northwest, but restricted views of the Pennines to the east.

The Bradshaw Hall and Gidlow Hall moated sites (Fig. 6) also are at quite high elevations of about 330 feet. Arley Hall is lower at about 290 feet and, like Haigh moated site, is on a quite flat “plateau”. Fig. 6. Bradshaw Hall and Gidlow Hall, Aspull, 1951 OS map.

Fig. 6. Bradshaw Hall and Gidlow Hall, Aspull, 1951 OS map.

For the Arley Hall moated site, Historic England8 states that “The platform would originally have been the site of a medieval hall building.”

OLD HAIGH HALL.

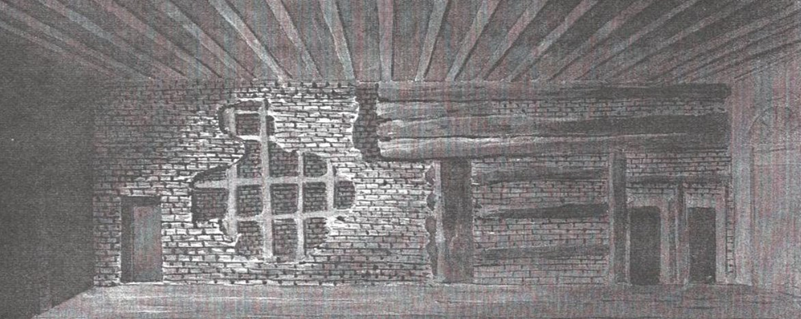

In his 1822 notes on the history and repairs of old Haigh Hall, James Lindsay supposes that the oldest part of the hall dates back to the Reign of Edward II [1307 -1327], done by Mabel. He also states, without evidence, that the roof of the old original building evidently stood before the conquest8. Fig. 7 shows a sketch of an old interior wall.

Fig. 7. James Lindsay’s sketch of an unidentified interior wall.

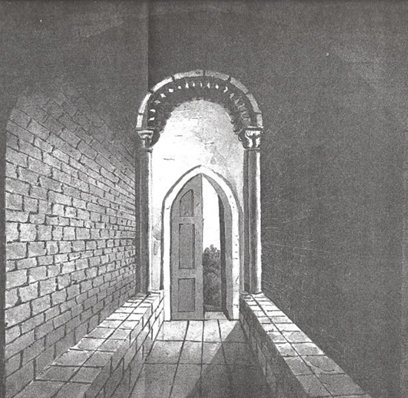

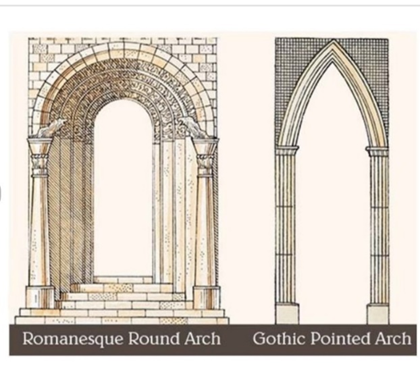

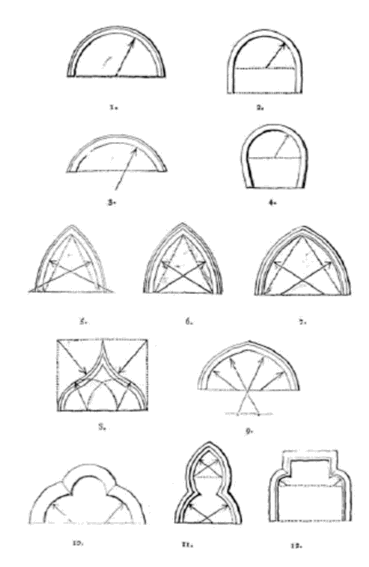

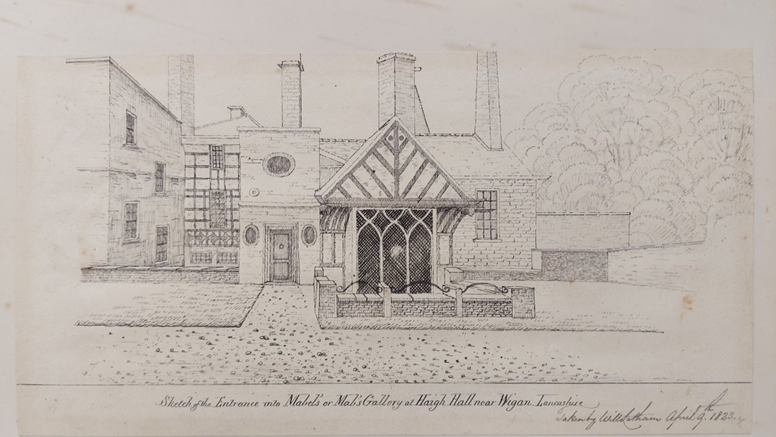

Kitts states that the round-headed doorway with chevron decoration and pilasters, at the end of a passage known as Mab’s Gallery (Fig. 8), is evidence that the Old Haigh Hall dated back to the late 12th century. But this interpretation does not address the more complicated nature of the doorway. Fig. 8 shows that the round-headed feature is above a pointed doorway. Fig.9 shows typical rounded-headed Romanesque and pointed Gothic arches. The Gothic period in England came after the Norman period and extended through the 16th century. Curved arches were also used in the Gothic period (Fig. 9), but pointed arches were not common in the Norman period. Figure 11 shows a Tudor (15th and 16th centuries) doorway with rounded and pointed arches. The entrance to Mab’s Gallery thus has elements of possible Norman and Gothic architecture and there is no documentary evidence for its construction.

Fig. 8. Entrance to ‘Mab’s Gallery’ in old Haigh Hall showing round-headed Romanesque doorway. Watercolour by James Lindsay, c.1800 (National Library of Scotland, acc. No. 25/3/5529.

Fig. 9. A typical Romanesque rounded arch and a typical Gothic pointed arch,

Fig. 10. Several types of arches used in Gothic architecture.

Fig. 11. A Tudor Arched Doorway.

The Mab’s Gallery itself has not been dated and the builder not identified. Just because it is called Mab’s Gallery doesn’t necessarily mean that Mabel built it, any more than she built Mab’s Cross on Standishgate. Bridgeman11 reports that James Lindsay noted that the name of Mab’s Gallery was in remembrance of Mabel Norris, not that she built it.

Kitts states that the building of the timber-framed chapel at Haigh has been attributed to William and Mabel Bradshaigh, but finds that there is no archaeological or documentary evidence to date the chapel next to Mab’s Gallery (Fig. 12 ). This timber framed section appears to be 16th century Tudor8. James Lindsay supposes that the stone south-west front was built by Mabel; “at all counts it cannot be of a later date, as the accounts of the family show that no such an undertaken was performed since that period, …”. However, from the fourteenth century there is a long gap in the documented history of Haigh Hall.

Fig. 12. Timber-framed section of old Haigh Hall, north-eastern front, entrance to Mab’s Gallery. Early nineteenth century sketch. Jim Meehan photo of original sketch in William Lathom’s Sketch Books, Lancashire Records Office (Ref. DP 291/2/3).

The legend about Lady Mabel remarrying a Welsh knight and doing penance by walking barefoot from Haigh to Wigan after her husband, Sir William Bradshaigh, returned to Haigh in 1322 is a myth. Sir William was involved in the 1315 Banastre Rebellion against the Earl of Lancaster and his supporters, particularly Sir Robert de Holland. Sir William was outlawed and his estates were forfeited to the King’s representative for a year and a day. The estates presumably included Haigh, Blackrod and Westleigh. Sir William was held prisoner at Kenilowrth, and later Pontefract Castle until August 1324 and his property was restored to him.

The interior wall in James Lindsay’s sketch (Fig. 7) is undated. Many modifications were made to the old hall from the 16th century. James Lindsay found that it was “very difficult to say how it has been pulled down and added to at different times”.

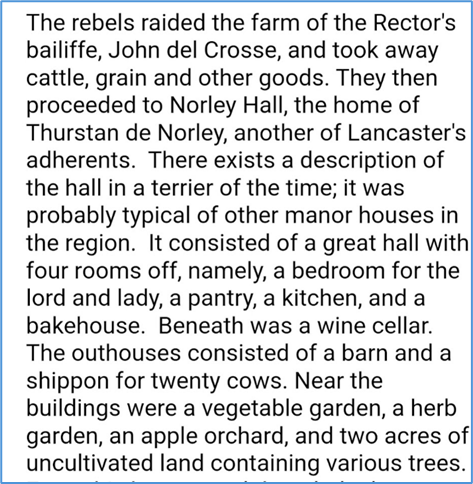

Blakeman provides a description of Norley Hall, about two miles west of Wigan at the time of the Banastre Rebellion in the 14th century (Fig 13) and states that it was probably typical of other manor houses at the time. Norley Hall was on a moated site. Perhaps this is also a fair description of a moated Haigh manor house, or perhaps the Old Haigh Hall.

Fig. 13. A 14th century description of Norley Hall.

In 1673 the manor of Haigh was described as 64 messuages (dwelling places), two water mills, a sawmill and 500 acres (could be Cheshire acres) of land. Haigh Hall was not mentioned.

BRADSHAIGH CHAPEL, WIGAN ALL SAINTS PARISH CHURCH

All Saints Parish Church has a long history13. In 1337 and 1338 Dame Mabel, the widow of Sir William de Bradshaigh “endowed a chantry dedicated to St Katherine the Virgin in the chapel of Blackrod in the parish of Bolton-le-Moors, and founded the chantry of St. Mary in the parish church of All Saints, Wigan, and endowed it with tenements in Wigan and Haigh”

A chantry is a foundation for the maintenance of one or more priests to offer up prayers for the soul of the founder, his family and ancestors and usually of all Christian souls. A chantry can mean either an endowment or foundation for the chanting of masses, or a chapel endowed by a chantry, or both. A chantry chapel can either mean a separate building or an area in a parish church reserved for the celebrations. The majority of chantries were founded at an existing altar15 and many endowments were for penances16. During the 14th and 15th centuries about two thousand chantries were founded.

Records indicate that Dame Mabel endowed a priest for the chanting of masses in a chapel in Blackrod (The Church of St. Katherine in Blackrod has a history dating back to at least 1138) and endowed a priest for the chanting of masses at the Altar of St. Mary in All Saints Church, Wigan. Bridgeman states that the chantry at the Altar of our Lady within the parish church of Wigan was founded in 1338. Nowhere in the historical records does it say that Lady Mabel endowed the construction, foundation, or maintenance of a chapel in All Saints Church. It is possible that Lady Mabel endowed the foundation of Bradshaigh Chapel.

John de Sutton was appointed the first chantry priest in Wigan Parish Church. Lady Mabel directed him and his successors to say mass for the souls of the former King, Edward II, her late husband Sir William, the late Bishop of Lichfield, all the faithful departed and, after her death, herself. On October 16, 1488, Sir William Holden was admitted to the same perpetual chantry, vacant by the death of Richard Fletcher11. Chantries were dissolved and their assets confiscated under the 1547 Chantries Act ordered by King Henry VIII as part of the Dissolution of the Monasteries, but in 1553 Hugh Cokesonne, fifty one years of age, was priest of the Virgin Mary Chantry and received a pension of three pounds and three pence, which was 5 shillings a year less than his usual income. The average income of a chantry priest after deductions was about 5 pounds, which was about twice as much as a weaver and half as much as a constable.

There is no documentary evidence for the foundation of Bradshaigh Chapel and no vestige remains of the original chapel20. With the enactment of the 1547 Chantries Act the Chapel was confiscated, fell in disrepair and was disused20. In 1620 Bishop Bridgeman rebuilt the chancel11. In 1679 Roger Bradshaigh sought permission to build a gallery over the burial site of the Bradshaigh family at the northeast end of the south aisle and by 1719 the chapel was restored. In the 19th century The Earl of Balcarres moved the Bradshaigh tombs and rebuilt the Chapel.

The two effigies on the altar tomb in the Chapel are said to be of Dame Mabel and Sir William Bradshaigh. However, there is no firm evidence that the two tombs contain the bodies of William and Mabel: the effergies are badly defaced and considered to be the effergies of William and Mabel; the female effergy was re-cut and the male effergy was copied by John Gibbs in about 1850. Blakeman11 notes that at that time no mention was made of bones being found. Blakeman also states that “Lady Mabel probably died in 1348, at the time of the Black Death, and her body was presumably laid in the tomb in the Bradshaigh Chapel.” There is speculation that the bones could be in some other part of the church

.Peter Layland, who has great knowledge of Wigan Parish Church, after considering the available evidence from limited national sources and local knowledge, finds that there is a strong probability that the Chantry at Wigan did involve the founding of the Bradshaigh Chapel for the following varied reasons.

“1. The funding involved was so generous that it continued to employ a priest until the 16th century. Academics have pointed out that many of the smaller chantries that were temporary and were generally carried out in an existing section of the church were smaller ones.2. The original terminology used talks about Lady Mabel “founding” the chantry of St Mary in the church of All Saints. This suggests a separate area or chapel otherwise surely it wouldn’t have a different name. [The original terminology states that the chantry was to be performed at the Altar of St. Mary in the Church, DW].3. However, the strongest evidence is that Sir William and Lady Mabel were almost certainly buried in the Chapel as evidenced by the remnants of their tombs and by tradition. This in my opinion practically guarantees that either the chapel was already existing at the time of the chantry or formed part of it. Either way it is noticeable as being an early example with most Chantries coming later in the Fifteenth century.4. Other circumstantial evidence includes the location of the chapel. Put simply it occupies the prime location for an additional chapel namely adjacent to the chancel / high altar on the sunny south side and is almost certainly the first separate chapel in an expanding church. Indeed some details of the pre 1840s church show Decorated Gothic details in the South Aisle suggesting expansion of the church in this direction in the Fourteenth century.”

CONCLUSIONS

There is no documentary evidence for the date of construction of the Haigh moated site and manor house, or who built them. It can be speculated that Hugh le Norreys, Lord of Haigh, occupied the first Haigh Manor House in the 12th century on the Haigh moated site.

There is no documentary evidence for the date of construction of Old Haigh Hall, or who built it, although it was probably built by the le Norreys or Bradshaighs. In the absence of documentary evidence, there is speculation that the Old Hall could have been built in the 12th century. There is quite firm evidence that parts of the Old Hall date from the 16th century. Many modifications and additions were made over the centuries until it was demolished by The Earl of Balcarres in the19th century and the present Haigh Hall was built on the same site.

Documentary evidence shows that in 1338 Dame Mabel endowed a priest to say mass at an altar in Wigan Parish Church. There is no firm evidence that the Bradshaigh Chapel in Wigan All Saints Parish Church was endowed or built by Dame Mabel Bradshaigh, or that the bodies of Dame Mabel and her husband, Sir William, are in the tombs in the Chapel. There is no documentary evidence to identify who built the chapel, or when it was built. It can be speculated that Lady Mabel did indeed endow a chantry chapel that became known as the Bradshaigh Chapel.

Derek Winstanley 2024

REFERENCES

1 www.wigan.gov.uk; Scheduled Ancient Monuments.

2 National Library of Scotland, Map images - National Library of Scotland (nls.uk).

3Walker, J.S.F. and Tindall, A.S., The Moated House, Greater Manchester Archaeological Unit, Country Houses of Greater Manchester, Chapter

4, chc4.pdf4Winstanley, Derek, 2023, Moated Sites in the Wigan Area, normal_64f0f601a9ddc.pdf (s123-cdn-static-d.com).

5Anderson, Donald, Life and Times at Haigh Hall, Smiths Books, Wigan,1991.

6Langton, William (Ed.), 1882, Visitation of Lancashire and a Part of Cheshire in A.D. 1533, Part II, Chatham Society, 1882), The Visitation of Lancashire and a Part of Cheshire.

7Arthur, H.H.G. Haigh Hall,1957, normal_634136854d01e.pdf (s123-cdn-static-d.com).

8Moated site at Arley Hall, Haigh near Wigan, Blackrod - 1014722 | Historic England

9Kitts, Maria, Haigh Hall: Out with the old in with the new, Y4780406, Archaeology of Buildings, MA thesis, Department of Archaeology, September 2010, Vols 1 and 2.

10 Bloxam, M.H. 1882, The Principles Gothic Church Architecture, Vol. 1, (ID:62181), principlesofgoth01bloxuoft.pdf.

11 Bridgeman, George T.O., 1889, The History of the Church & Manor of Wigan, Part I, Chetham Society, 46, Bridgeman, George T.O., 1888, The History of the Church & Manor of Wigan in the County of Lancaster

12 Blakeman, Bob, 1989, Mab’s Cross - Legend and Reality, Mabs Cross Legend and Reality (wiganarchsoc.co.uk).

13Farrer, William, Brownbill J. (Eds.), 1911, Townships: Haigh, A History of the County of Lancaster: Vol. 4, Victoria County History, London, A History of the County of Lancaster | British History Online.

14The parish of Wigan: Introduction, church and charities, A History of the County of Lancaster: Vol. 4, Victoria County History, London, 1911, The parish of Wigan: Introduction, church and charities | British History Online.

15 Muir, Curryer and Hawkes, Arthur J., 1930, Ancient and Loyal, wiganworld - Wigan, Ancient and Loyal.

16Cutts, Edward, L.,1898, Parish priests and their people in the Middle Ages in England, Chapter XXVIII, The Chantry, Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, London, Parish priests and their people in the middle ages in england.

17Cook, H., 1968, Medieval chantries and chantry chapels, John Baker, London, MEDIAEVAL CHANTRIES AND CHANTRY CHAPELS : G. H. COOK : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming : Internet Archive.

18Lorenz, Mirko, 2022, What can we learn from medieval prices and wages? What can we learn from medieval prices and wages? - Datawrapper Blog

19Raines, F.R., 1862, History of the Chantries within the County Palatine of Lancaster, The Chetham Society, Vol. 59, A History of the Chantries Within the County Palatine of Lancaster.

20Forest, Michael, The Living Church The Reverend Michael Forest, YouTube. Link

21Peter Layland, personal communication with Derek Winstanley, October 2, 2024.