“GOT ANY GUM, CHUM?” : AMERICAN SOLDIERS AT ASHTON AND GOLBORNE IN 1944

Ahead of the “D-Day” landings on the Normandy coast in June 1944, thousands of American soldiers were stationed in and around Ashton and Golborne. Most were members of the 79th US Infantry Division under the command of Major-General Ira T Wyche and were billeted at Garswood and Golborne Parks - now, respectively, home to the Ashton-in-Makefield and Haydock Park Golf Clubs. Both locations had been requisitioned for military use early in the War and were prepared for the 79th by an advance party that arrived in the UK on 5 April 1944. Haydock Racecourse was also used by the US military, and would be formally activated as “AAF Station 530” on 13 November 1944.

Some of the soldiers' experiences and impressions of the area, taken from their memoirs, private journals and official regimental histories, are given below.

Note that local place-names are frequently misspelled in the American documents - so Golborne appears as “Goulborne” or “Goldborne”, Makerfield as “Makersfield”, Wigan as “Wiggan” etc. For the most part these have been left uncorrected.

More in my flickr presentation “WW2 US Army Bases” at https://www.flickr.com/photos/themakerfieldrambler/albums/72157654894394174/.

++++++++++++++++

John “Jack” Cabeen Beatty (1919-2016)

From “The Politics of Public Ventures: An Oregon Memoir”, J C Beatty (Xlibris 2010):

“In March we moved by train to Camp Miles Standish and the Boston Port of Embarkation. There we were sealed off – no leave, no passes, no visitors and, toward the end of our stay, no telephone calls... The fact that the division was embarking was as secret of the date of embarkation. Our guns, battery equipment and vehicles had been turned in at Camp Philips; all we took with us were our personal effects and side arms...

We sailed with a substantial part of our division on the [HMS] Strathmore, a 230000 ton British liner chartered from the Peninsular and Oriental Steamship Co... The dining room was immense, two decks in height. The waiters wore black tie, and each dinner had a soup course, a fish course, a meat course entree and desert. We loved it... Daylight hours we were allowed on deck. The convoy [of ships] stretched as far as the eye could see in every direction...

Early in April after eight days at sea we sailed up the Clyde... When A Battery disembarked, it was dark, and we boarded a troop train with sealed blinds covering the windows. We travelled some hours, and eventually detrained at a railhead near a town called Wiggan 25 miles east of Liverpool. The entire division of some 16000 troops was billeted on the grounds of the estate of the Earl of Garswood* surrounded by a brick wall 8ft high. The estate was adjacent to a village called Ashton in Makersfield. We were quartered in rows of pyramidal tents, and the scene reminded me of Brady photographs of the Army of the Potomac in winter quarters. It was cold and it rained day after day. All we did for nearly a month was huddle in tents trying to keep warm and dry. The ground water level appeared to be at ground level. The paths were awash. The latrines were ghastly, consisting of wooden planks with holes in them under which were tall metal buckets. These buckets were supposed to be emptied each day by contractors who came through the camp with horse drawn vehicles known as honey wagons. The contents were no doubt returned to the fields in an organic cycle. Some days the honey wagons didn't show up, and desperate men ran along the planks looking into the holes searching for one not full to the brim.

When I was off duty and the rain let up, I walked through the countryside to get some feel for the locality. In that area the houses were nearly all hidden behind tall walls and heavy planting. You rarely got a look at a house. I walked into Wiggan several times. On one occasion an Englishman invited me and a companion to come to the Conservative Club** for a drink. He stood us each a stiff drink of scotch, a rare commodity, and related a cornucopia of offcolor stories. At battery level we had no maps, no equipment and no information as to what we were going to do. It was a very uncomfortable month. Finally [Captain John A] Hinkle and I bought a three-speed English bicycle and for several days we were able to extend the perimeter of our exploration.

The weather improved and we resumed intensive training, although we had no space for manoeuvre and no range on which to fire. The training program now concentrated on an obstacle course through which we crawled, avoiding barbed wire while machine guns fired overhead...

Near the first of May our equipment, all brand new, arrived by ship, and I went to the Liverpool docks with a party of drivers and gun crews to pick up our trucks, guns and uncrate the remainder of our equipment. Once this was done we prepared to move south to calibrate the guns... Leaving Wiggan meant leaving the bike. There was no room to transport it. Captain Hinkle bought my half interest, saying he would ship the bike home...

Training in Wales was interrupted by orders to return to Ashton where we packed and loaded our equipment on the trucks and drew a full load of ammunition. We knew then that the invasion was imminent. The only questions were when and where. The latter part of May, the 79th moved south from Wiggan to the Channel coast... On June 10 we learned that the 313th Infantry, our combat team partner, had left their encampment... March order [for us] came at 4am on the morning of June 13...”.

Jack Beatty was born in Washington DC but moved with his family to Portland, Oregon, in 1920. In July 1942 he was commissioned as a second lieutenant and assigned to the 79th Infantry Division. After the War he attended Columbia University Law School, graduating in 1948. He then returned to Oregon with his wife Clarissa (shown with him in the photograph taken on their wedding day in 1943) and worked as a lawyer and judge and in various other public service roles. Following Clarissa's death in 1996, he was reunited with his high school sweetheart, Virginia; they married in 1997.

The 310th Field Artillery Battalion and units of the 313th Infantry Regiment, all part of the 79th US Infantry Division, had been stationed at Garswood Park from 19 April until 1 June 1944. The 310th finally departed Weymouth for the French coast at 10am on D Day+8, 14 June, having enjoyed what would be their last hot meal until September that year. Jack served with 'A' Battery as firing executive and then as battery commander, fighting his way from Normandy to what was then Czechoslovakia. He received a battlefield promotion to captain and the Bronze Star, and the 310th received a Presidential Citation.

*The “Earl of Garswood” was in fact Frederick John Gerard (1883-1953), the 3rd Baron Gerard of Bryn. **The former Conservative & Unionist Club, where Jack was regaled with “a cornucopia of offcolor stories”, still stands on Princess Road, Ashton.

Extract from the official “History of the 313th Infantry in World War II” (Col Sterling A Wood etc.; Washington Infantry Journal Press, 1947)

“The 313th Infantry was to be allocated a bivouac area in a location which had formerly been a public park, known as Garswood Park, in the town of Ashton in Makersfield, Lancashire, England. When the advance party arrived there, however, it was found that the area was not sufficient to accommodate all of the 313th Infantry, and because of this, the Regiment was split up for the first time.... The bulk of the troops, including the 310th Field Artillery Battalion,were to be located at Garswood Park. The remaining troops were to be located in an area known as Marbury Hall, Cheshire...

Both Garswood Park and Marbury Hall were almost completely devoid of facilities when the advance party arrived. Both areas had a few barrel-shaped buildings scattered about, which were used as kitchens and administrative buildings. But aside from these few structures neither location gave any evidence of being a probable camp site. To further complicate matters there were only four vehicles available, and these were divided equally between the two camps. All supplies had to be requisitioned and were slow in arriving. Companies C and D of the 749th Tank Battalion, already stationed in England, were detailed to assist in putting up the pyramidal tents which later served to house the troops. Despite all difficulties both camps were ready to receive the troops when they arrived six days following the arrival of the advance party. The pyramidal tents gave both areas the appearance of a camp, and all preparations were far enough along that the troops moved in on schedule...

In the early weeks the weather was cold and damp, and at night the dampness seeped through the thin layer of canvas on the Army cots, and many a soldier shivered in his tent "hotel". It was a common practice to sleep with one's clothes on; in fact, it was uncommon in those early days in England to find a soldier who removed more than his GI shoes when he turned in. Then, too, there was little space for training, and as a consequence, the training while in England was confined predominantly to frequent hikes, marches and platoon or company problems. Later, frequent night problems and operations were conducted, and on the whole, much valuable experience was gained during the period that the 313th Infantry remained on British soil.

Morale was generally high throughout the entire period that the 313th Infantry remained in England. Almost from the very beginning passes were granted. Fifty per cent of the Regiment were allowed on pass at any one time to visit nearby towns, and on weekends, members of the Regiment visited the larger cities located within a one-hundred-mile radius of Garswood Park and Marbury Hall. Night after night the pubs of the surrounding towns were filled to overflowing with American troops. They drank freely of English beer, sang American and English songs, and mingled with Tommies and civilians...

It was strongly impressed upon the troops that a severe scarcity of goods and food existed through the British Isles. Soldiers were warned not to buy food or goods anywhere while on pass, and more, were asked not to accept the hospitality of English civilians who offered food to American troops. [Nevertheless] the English did their best to make the troops feel at home during their stay. Many soldiers formed life-long friends while there, and since both the Americans and the English spoke a common tongue, it was a simple matter to get acquainted. Only the children were at all forward in approaching the Americans. Wherever an American soldier went, small children would follow them in droves, chanting the familiar “Any gum, chum?” And even though the soldier's ration for gum was only two packages per week, the kids usually got what they were after...

On May 12, a retreat parade was held at Garswood Park. The affair had been scheduled in order that the townspeople of Ashton in Makersfield might witness American soldiers on dress parade. Much interest had been shown by the local townspeople in the activities of the American soldiers stationed there. The retreat parade, therefore, was scheduled predominantly for their benefit. The public turned out in large numbers to witness the event, which was highly colorful and in no small sense of the word, inspiring. The 3rd Battalion was selected as the honor battalion for the occasion, and F Company of the 2nd Battalion was chosen as color guard. It was more than evident as the ceremonies progressed that the townspeople of Ashton in Makersfield were deeply impressed by the occasion.

As the month of May drew toward a close all members of the 313th Infantry felt quite at home in their new environment. The weather had become somewhat warmer, and with the privilege of nightly passes life had become interesting and pleasant for the troops. The officers of the staff, meanwhile, had moved into a luxurious home located not far from Garswood Park* in the town of Ashton in Makersfield, where they enjoyed the comfort of home life in a manner surpassing even the better Army days in the United States. For these and other reasons no one was particularly anxious to leave England, although one and all knew full well that the time for movement elsewhere was rapidly approaching...”.

*I am not sure which “luxurious home not far from Garswood Park” was put at the officers' disposal. Can anyone identify it?

Walton Starkes Van Arsdale (1908-1984)

From “The Diaries of Col. Walton S. Van Arsdale, 311th Field Artillery Battalion, 79th Infantry Division, US Army” (©Van Arsdale Family, used by permission):

“We were billeted on an English golf course named Golborne Park, a private golf club.* The administrative buildings such as kitchen and mess halls and Battalion Headquarters consisted of quanset huts. All other quarters for enlisted men and officers were tents. We shared the entire area with our combat team, the 314th Infantry Regiment.

The game of orientation, attending lectures and classes, censoring mail, etc. started and continued throughout our stay in England. Daylight hours were long, 4am to 11pm. We were out shortly after daylight and worked ‘til just before dark. A psychiatrist, a Captain of Medics, made several talks on mental conditions during combat. I received a package, my first overseas, that had, amongst other things, pickled peppers. We all had a hot time that night at meal time.

The only recreation we have is to spend our evenings at the golf club. Not much to do but drink half & half – ale very low in alcoholic content. After several hours the intake was more liquid than effect. The club closed at 2200 hrs, then to our tents and off to bed. I was awakened at 0200 hrs to visit the honey bucket, then back to bed. The honey buckets were large portable, steel containers to act as toilets, replacing the slit trenches. These buckets were picked up each day and put onto horse drawn carts, to be taken away for fertilizer.

One day, officers and high grade noncommissioned officers were marched to a theatre where we heard speeches from Lt. General George S. Patton, 3rd Army, Major General Troy H. Middleton, VIII Corps, and Major General Ira T. Wyche C.G., 79th Infantry Division.

On June 10, at 0200 hrs, a call for Colonel Foote came in from Division Artillery, ordering the Battalion to proceed immediately to a prearranged assembly area near Bristol...”.

Walton S Van Arsdale was born and died in Georgia, USA. His war diary begins on 16 April 1944, the date HMS Strathmore docked at Gourock on the Firth of Clyde. There the soldiers remained for two days, attending lectures on what they should expect and how they were to behave whilst in the UK. On 18th April they were finally allowed to disembark and boarded a troop train which brought them to Newton-le-Willows station around 7pm. From there they marched in formation to Golborne Park. Walton eventually reached the Normandy coast (Utah Beach) via Bristol and Weymouth on D Day+12, 18th June, his unit's first significant engagement with the enemy being the battle for Cherbourg. The family understands that Walton was at this stage a Captain or Major, advancing to the rank of Colonel as the War progressed.

*Haydock Park Golf Club had relocated to Golborne Park - to the south of the town of Golborne, between Newton Lane and Warrington Road - in 1921. However the Club retained its original name, a source of much confusion ever since...

Donald E Alexander (1920-2016)

From “Quiet Warriors: Veterans' Military Service Memories”, Blake E Edwards (ed) (Xlibris, 2008):

“We boarded a train and arrived at a location between Manchester and Liverpool, England, called “Goldbourne Park”. We eventually ended up on a golf course at Newton Le Willows, England. We were once again in a tent city. It was a nice campsite and the clubhouse was converted into Officers' Quarters. There we could play snooker (a game of pool) in the evenings.

The first order of business was to inventory the newly issued equipment, consisting of three batteries of new 105mm howitzers and all vehicles, survey equipment, parts etc associated with an artillery battalion. The weather there was also miserable, being wet, rainy and foggy most of the time...

We had a pep talk from General George Patton …

During our stay at Newton Le Willows we were with the 314th Infantry Regiment. Together we formed Combat Team #4 of the 79th Infantry Division.

A trip to Wales for firing practice was interrupted by orders to return to England. This later turned out to be preparation for the invasion of the European Continent.

About May 25th, 1944, we loaded up all our equipment and headed down for the port city of South Hampton... The trip down was quite interesting because of the narrow roads that we took. The amount of equipment stored long the roadways was just unbelievable. Tanks, trucks and jeeps were parked solidly. Where equipment wasn't parked along the road, ammunition was parked....

On June 11th, after six more days in the rain, we finally got our orders that we were going to be invading France...”.

Landing at Utah Beach on D Day+6, 12 June, Donald Alexander served as Forward Observer and Reconnaissance officer with “C” Battery, 311th Field Artillery Battalion. His personal World War II ended near Dortmand, Germany, on 17 April 1945; Donald was awarded 5 battle stars plus other ribbons including the Bronze Star and left the army with the rank of Captain. Later he joined the reserves and was recalled to active duty in the Korean War; Donald again distinguished himself, and was awarded another Bronze Star.

Extract from the official history of the 314th Infantry Regiment (“Through Combat...”, Col. W A Robinson)

“On March 22 [1944], the 314th departed Camp Phillips [Kansas] for the war, going by way of Camp Myles Standish and the Boston Port of Embarkation... 48 hours before sailing, the division was restricted to the camp limits. Telephone service was shut down altogether, and all mail had to be submitted to company censors...

The regiment was assigned to two ships, with the 1st and 3rd Battalions, Regimental Headquarters, Anti-Tank and Service Companies sharing the USS Cristobal, and the 2nd Battalion and Cannon Company boarding HMS Strathmore. The company commanders stood by at the foot of the gangplank to make sure nobody got left behind. The Strathmore was an English ship with an Indian crew and formerly had been on the run from Liverpool to Bombay, while the Cristobal had done peacetime duty as a banana boat on the South American trade routes, and now was manned by Merchant Marine personnel...

The convoy split up off Ireland, and the Strathmore, with 2nd Battalion and Cannon Company aboard, swung north to land at Glasgow April 16, while the rest of the 314th headed into Liverpool on the Cristobal, docking there on the 17th... While the officers received a briefing on how the men were supposed to behave in England, the men stood on deck throwing cigarettes and coins to the pier below to watch the dockhands scrimmage for them. That, it developed, was one of the things they weren't supposed to do, but it was the first hint of the purchasing power of the PX [US equivalent of NAAFI] ration in tobaccoless, candyless, soapless Europe.

The compartments having passed inspection, the boys climbed into their pack harness and wrestled their duffle bags up the narrow companionways to the gangplank, and down to the pier, where the pint-sized English trains stood waiting...

Mid-April was late in the pre-invasion day, and there was little room to spare in the United Kingdom, between the camps and the vast supply dumps. Without space available to close in a regiment, let alone a division, the 314th had to divide itself between two tent areas, one at Goldborne Park, near Newton-le-Willows, halfway between Liverpool and Manchester, and the other at Tatton Park, near Knutesford, some twenty miles away. The tents at Goldborne Park were pegged down on what had been a golf course in more carefree days, and there the 1st and 2nd Battalions set up, along with regimental Headquarters and Service Companies...

The English money took a good deal of getting used to, and so did the English, but the 314th learned quickly. From the beginner's stage, when you thrust out a fistful of assorted coins at the innkeeper and let him take his pick, you could soon tell the difference between a half-crown and a florin. By then you'd also learned that a village pub, like the “Bull's Head” next to Goldborne Park, was the local lodge, a place to have a quiet glass of half-and-half and play a few games of darts, and no relation whatever to the rowdy juke joints in the army post towns back home.* The beer's alcoholic content would have suited Mrs Boole's W[omens] C[hristian] T[emperance] U[nion] standards, but it had a way of multiplying inside you, which made for a wakeful night if not a very boisterous one. Only the early settlers could remember when there had been Scotch for sale...

At one assembly, the officers and first-three-graders heard speeches by Lt. Gen. George S Patton, Jr., Maj. Gen. Troy H Middleton... and the 79th's own Major General I T Wyche. General Patton led off the speakers, and, as always, he was a hard man to follow on the platform, as his famous brand of brimstone oratory, while it was nothing for a family newspaper, was just the sort of blunt locker-room talk the men had wanted to hear.

It was here at Goldborne Park that Lt Colonel Robinson received his promotion to Colonel and the silver eagles to go with it...”.

The 314th departed for Southampton docks, and thereafter Utah Beach, on D Day+7, 13 June.

*The Bull's Head at the corner of Southworth Road and Golborne Dale Road closed some years ago. The building has since been converted to office accommodation and is known as The Southworth Business Suites.

George Smith Patton (1885-1945)

Whilst researching the American military units that were stationed in and around Ashton I was intrigued by several references to the troops having heard an address by General George S Patton, commander of the US Seventh and later the Third Army.

The diary of 79th Infantry Division commender Major-General Ira T Wyche, now preserved at East Carolina University, mentions that a scheduled visit to the area by General Patton on 11 May 1944 had been cancelled at short notice. The timing is significant because, just a few weeks earlier on 25 April, Patton had made a diplomatic gaffe by appearing to rule out any post-War role for the USSR outside its own borders.

By mid-May the anger of Supreme Allied Commander Dwight D Eisenhower towards General Patton had abated, and he was given leave to resume his round of talks on the understanding that “you will not be guilty of another indiscretion which can cause any further embarrassment to your superiors or to yourself”. I inferred from a subsequent entry in Major General Wyche's diary that General Patton must have addressed the troops in Ashton on 16 May.

Verification came later in a series of Staff Meeting reports also in the East Carolina University archive, the report for 15 May 1944 confirming that the venue was in fact The Queen's Theatre on Wigan Road, Ashton.

A scan of the relevant extract from General Patton's diary which I subsequently obtained from the US Library of Congress added no further detail, but it was good to see a record of the day's events written in Patton's own hand - knowing, as I now did, that he was referring to a visit to my home town.

So what did General Patton actually say at Ashton? According to biographer Martin Blumenson, it was about this time that Patton began to give the speech – or a variation of it - made famous by the 1970 biopic starring George C Scott. “Since he spoke extemporaneously, there were several versions. But if the words were always somewhat different, the message was always the same: the necessity to fight, … to kill the enemy viciously, … for everyone, no matter what his job, to do his duty. The officers were usually uncomfortable with the profanity he used. The enlisted men loved it.” Terry Brighton, another biographer, calls Patton's speech "the greatest motivational speech of the war and perhaps of all time, exceeding (in its morale boosting effect if not as literature) the words Shakespeare gave King Henry V at Agincourt". The effect on the audience at Ashton is confirmed by the recollections of Donald Alexander of the 311th Field Artillery, then camped alongside the 314th Infantry at Golborne Park:

“Patton was everything he was claimed to be. He frightened every man who saw him purely out of the respect soldiers had for him. As he was introduced to the Division officers the auditorium was so silent one could hear a pin drop, as the expression goes. He was decked out in his riding breeches, boots, spurs, fitted Eisenhower jacket, several lacquer layered and starred helmet liners, and pearl handled pistols... His language was as filthy as described in biographies. He was an interesting personality. I'm happy to have been exposed to such a gallant, dedicated and strange soldier. I saw Patton again briefly in Normandy... He was riding atop one of the tanks as they passed our column. He was a real character”.

George S Patton died from injuries sustained in a car accident in Germany just over 7 months after the Nazi surrender.

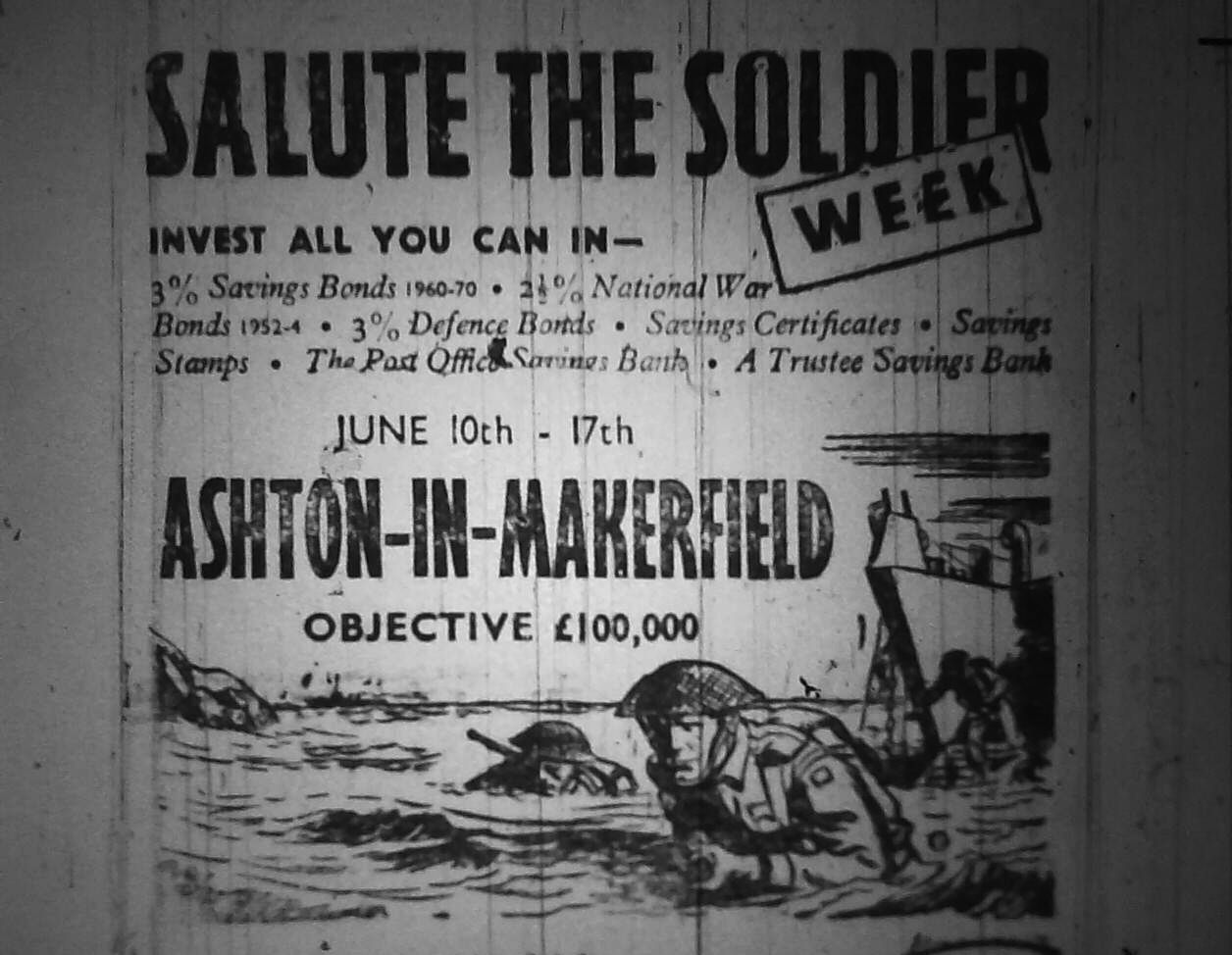

Henry Gordon “Doug” Douglas (1904-1967) and Ashton's “Salute The Soldier” Week

From The Wigan Observer & District Advertiser, 13 June 1944:

“SALUTE THE SOLDIER: USA COLONEL OPENS ASHTON WEEK. A large assembly of townspeople witnessed the opening ceremony of Ashton in Makerfield's Salute The Soldier week campaign on Saturday in Gerard-street, in front of Messrs Crompton's works, where a platform, which also formed a saluting base, had been erected. Flags of Great Britain, America and our other allies were fixed, at appropriate distances, near the edge of the parapet from the Wigan-road end to the platform, and these, together with streamers and flags decorating the platform and buildings, gave the street a most colourful appearance...

Col Henry G Douglas, of the US Army, was the opener, and Councillor J Derbyshire JP (Chairman, Ashton District Council) presided, and supporting them on the platform [was] the Earl of Derby PC, KG... The Chairman extended a welcome to Lord Derby, whom he described as the grand old man of Lancashire, and to Col Douglas [who] had come many thousands of miles to help our lads finish the job. The more the townspeople loaned, the bigger and finer would be their salute and their investments would help shorten the war.

Col Douglas said they should think of the Salute The Soldier campaign as a greeting between fighting men and women and those who stayed at home. Those in war industries and those who saved and loaned were truly fighting as much as those who manned the guns. Their Salute to the Soldier was the saving and loaning of every penny in order to keep the soldier going. That was needed now more than ever. The war news was good, but the battle was not won. A salute was not a one-sided affair; it must be returned, and they could be sure that their Salute to the Soldier would be returned. The soldiers were on their way to Berlin; let them in Ashton keep their division going – that was the object of their £100,000 target. After stating that Ashton had beaten their target in previous national savings week campaigns, Col Douglas said there was more of an incentive to save now that they could see victory in the offing. It was never in doubt, [and] it was now a certainty. Therefore the people of Ashton ought to go “over the top” with a bang in their campaign.

Lord Derby, who was afforded a very great welcome, said... he never thought he would speak on a platform in this country with an American... He desired to thank the Colonel and his countrymen for all they were doing to help us...

Mr [R D] Dixon [Manager, Westminster Bank, Ashton Branch] presented Colonel Douglas with a miniature pair of clogs and a piece of Lancashire coal mounted on a stand as a memento of the occasion...”

Born into a military family, “Doug” Douglas graduated from the prestigious US military academy at West Point in 1927. In 1943 he was promoted to the rank of colonel and took command of the 1102nd Engineer Combat Group. The Group was billeted at Garswood Park in May-June 1944 before being deployed to France. For its role in the Battle of the Bulge the Group's HQ was awarded the Luxembourg Croix de Guerre. Doug was personally awarded the Bronze Star Medal and French Croix de Guerre. By this time also a veteran of the Korean War, his last two years before retirement in May 1957 were as Professor of Military Science and Tactics at Texas Technological College.

“Salute the Soldier” was a scheme during WW2 to encourage civilians to invest in War Bonds, Savings Bonds, Defence Bonds and Savings Certificates. From June 1944, with the Allied invasion of continental Europe now under way, the focus switched to specific strategic objectives related to the invasion. £100,000 was said to be “the cost of moving a division from Ashton to Berlin”.

Ashton-in-Makerfield's “Salute the Soldier” week began on Saturday 10 June 1944 with a ceremony in front of Crompton's engineering works on Gerard Street as reported above. Further events were scheduled throughout the Week, including a “detour of the town” by “a Motorised Column of American Engineers with Full Equipment”. The particular unit is not identified in local reporting, but from records of US troop disbursements and given the prominent role taken by its commanding officer it is reasonable to suppose that the Column comprised members of the 1102nd Engineer Combat Group with possible support from the 44th Engineer Combat Battalion HQ. All other US Army units previously stationed at Garswood Park had by this time left for France.

The Wigan Examiner reported afterwards that: “The total amount invested was £121,920, or £6.16.6 per head of the population, which compares very favourably with other neighbouring districts. Of this total the schools raised £19.454.4.10, or over £1296 per school.”

The plaques awarded in recognition of this achievement and an earlier “Wings For Victory” campaign in 1943 were at one time displayed in the library; they are now in private ownership.

John Andrew Bedway (1920-2007)

This photograph and following description are posted by kind permission of Barbara Bedway of New York State, with whom I corresponded in 2015:

“The photo is of my father, John Bedway, at the Haydock Park Race Course, site of a U.S. Army Recovery Center during World War II. My father, who died in 2007, spoke often of his service in this little-known unit of the Army, set up at a racetrack where each horse stall was converted into a two-bed billet. He’d been assigned to the infantry, but two weeks after landing as a private in England in 1944, he was pulled out and told he was going to help set up this recovery unit, for “soldiers who can’t perform their duty, but the docs can find nothing wrong with them”. A lot of the men had been under constant fire, in the South Pacific, in Italy and Germany. The men had to be kept busy and fit — the Army didn’t want to send them back to the States. My father was chosen, he said, because the Army had been combing soldiers’ records for anybody with a background that could help in the rehabilitation of soldiers, and my father had four years of teacher training at the University of Cincinnati, and was a physical education major.... He told me:

“When they found out I had a driver's license, they gave me a scrap of paper with an address in London on it, told me to drive to that address and pick up equipment for the unit, which would have about 150 men. I had to put blackout lights on the truck - you only had a slit of about a quarter inch while you were driving. When the sirens sounded, every light in the city went out. I ran up over the sidewalk on every turn through those narrow streets. When I saw a uniform, I would stop and ask directions. I picked up lumber, ping-pong tables, typewriters. Somehow I made it back.

The [recovery] unit was inside a big racetrack; we lived in stables. The commanding officer in charge was a Captain Sipes, and Lt. Giler was in charge of the program. I had platforms built and made out a schedule - it was just basic training all over again. But you had to try to make it rougher, so they'd want to go back [to active service]: reveille at six, breakfast at 7, close-order drill, hiking, map reading, training films to watch. There was no weapons instruction. Practically as soon as I'd made out the schedule, I was made a sergeant. When we had our first inspection, Capt. Sipes was given a commendation and Legion of Merit.

I remember one guy insisted his left arm was paralyzed. He would grab his left thumb with his right hand and pull it up to salute. We couldn't convince him there was nothing wrong. A lot of the men were simply terrified; they'd been under fire, fairly constantly, in the South Pacific, in Germany. We had a combat division that had been through hell in Italy. Guys got out of one engagement and freaked out when they had to go to another.

One kid went AWOL, and they put him in the stockade. The nickname for the guys put there was "Colonel Killen's Navy" - they wore Navy surplus. This kid asked to go the latrine, and while he was there, he took the cardboard core out of the toilet paper and filled it with dirt. When he walked back to the tents, he threw this dirt at the guard, and ran. The guard shot him as he ran away. Medics were working on him when I got there, and I asked the guard: "Why did you shoot him?" He said he fired over his head and shouted for him to halt, and when the guy didn't stop, he shot him. "Then how do you account for the fact there are two bullet holes in him?" I had to ask. A 32-caliber pistol makes a neat wound, and there were two of them. That kid lived, and the guard got no reprimand.

All the ones who were real bad were put in the stockade. One kid, anyone could see he was terrified all the time. His eyes were blank, and he flinched when you came close. He never talked. We had no psychiatrists, no one doing anything of that nature. Early one morning, some guys ran to get me. The kid had used his tent rope to hang himself in the boiler room. The ceilings were low there. I worked on him, till the medics came. I was giving him artificial respiration when they told me to stop, he wasn't going to make it. Anyone could see that kid was not right, that putting him in a guard house was the last thing he needed.”

My father stayed with that unit for ten months, then volunteered for a two-month officer training course that eventually landed him with the First Division in Germany. When post-traumatic stress disorder finally became a mainstream term, an actual diagnosis, he thought young soldiers might have a decent chance to recover. But he never used the term, PTSD; he always used the older term, “soldier’s heart.””

Through his service with the 1st Infantry Division - “the Big Red One” - John earned a further promotion to the rank of captain. After the War he returned to his birth state of Ohio where he completed his education degree, married and co-founded the Bedway Coal Co. He also served with various community organisations including the Scouting Heritage Society, the National Trail Council, the University of Steubenville Board of Trustees and the Regional Advisory Board of United National Bank.

Recovery Center No.1 remained at Haydock Racecourse until 10 May 1945. In spite of its obvious shortcomings it was then re-established on more or less similar lines on the European mainland.

THE MAKERFIELD RAMBLER

June 2024