Wigan & the Slave Trade

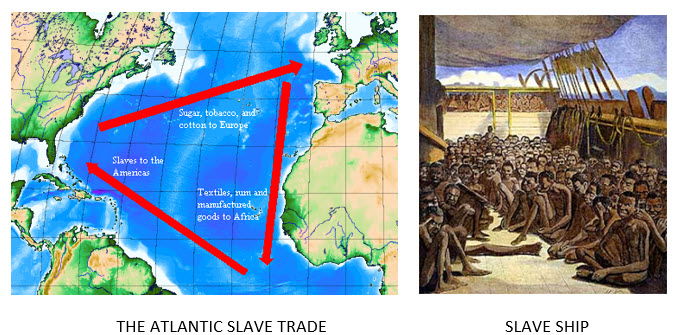

Three hundred and fifty years ago, slaves from Africa started to be shipped to north America and the Caribbean in large numbers. Liverpool became a major port for the slave trade and Liverpool merchants and bankers grew rich from the slave trade. Some of these merchants and bankers invested in the coal fields around Wigan and some Wiganers also participated in the slave trade and became rich. This paper documents from numerous historical records the influence of the slave trade on the development of Wigan and the roles of people from south Lancashire, especially Wigan, in the slave trade.

From the mid-18th through the mid-19th centuries, Wigan and surrounding townships grew rapidly to become a significant hub in the Industrial Revolution that spread across the world. Population in the Wigan area mushroomed on the back of coal, cotton and iron industries, fuelled by private wealth and entrepreneurship.

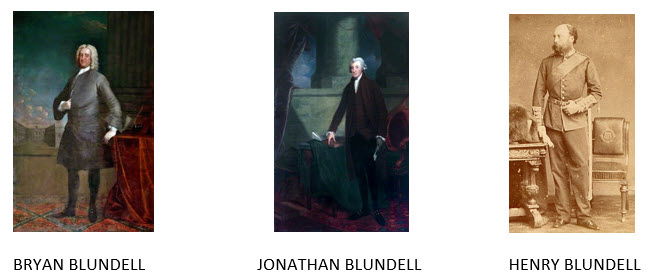

It was construction of the Leeds-Liverpool canal that opened up large-scale coal production in the Wigan area in the 1770s. Local people were influential in constructing the canal, but we see the appearance of rich and powerful ‘foreigners’ from Liverpool and Bradford. John Hustler and Thomas Hardcastle were Bradford wool staplers and merchants and Jonathan Blundell, William Earle and John Hollinshead were Liverpool merchants. All served as members of the Leeds–Liverpool Canal Committee and they provided substantial investments to develop waterways, railways, and collieries.

In 1774 Jonathan Blundell started to mine coal in Orrell and in the 1800s the Blundell family mined coal in Ince, Wigan, Blackrod, Chorley, Winstanley and Pemberton. Coal production at Blundell’s Pemberton Collieries rocketed to a peak of 738,000 tons in 1913, when it was the largest colliery in Lancashire.

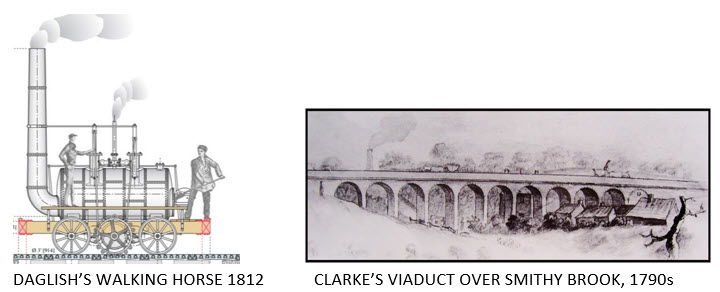

Over one hundred steam locomotives were built at Haigh Foundry owned by the Earl of Balcarres, including The Walking Horse in 1812 and two more steam locomotives by 1816. The Walking Horse, operating on John Clarke’s Winstanley and Orrell colliery railway, was the third commercially successful steam locomotive in the world and the first to cross a stone viaduct. The Earl’s collieries, together with the Kirkless Hall Coal and Iron Co. Ltd. and two smaller concerns, formed the nucleus of the vast Wigan Coal and Iron Company established in 1865 as the largest joint-stock company in the country, excluding railways.

So, where did the Blundell’s, Clarke and the Earl of Balcarres get their money?

Through the late 18th century, landowners, merchants, bankers, ministers, lawyers and manufacturers supplied capital to finance relatively small-scale mining and quarrying operations in the Wigan area. Colliery owners Leigh, Woodcock, Berry, Bankes, Bradshaigh, Prescott, Culshaw, Dawson, Hardy, Jackson, Jarrett, Laithwaite, Langshaw, Lofthouse, Peckover, Monk, Townsend, Brimilow, Bradshaw, Stephen, Whaley, Barton, Hodson, Hatton, Winstanley, Claughton and the German family fall into this category; and Longhbotham, Chadwick and Haliburton can be added by including engineers and ironmasters. However, large infusions of capital were needed to sustain and expand the coal production industry and many of these people were incapable of making the necessary investments.

In his book ‘The Orrell Coalfield’, Donald Anderson mentions that Liverpool’s corporation “pursued a very enlightened policy” and engaged extensively in the slave trade. He reports that Bryan Blundell engaged in the slave trade, founded Liverpool’s first charity school, the Bluecoat School, and was instrumental in founding Liverpool Infirmary, Warrington Academy and 36 alms houses in Liverpool. His son, Jonathan, became treasurer of the school and Colonel Henry Blundell owned Pemberton Collieries and built St. Matthew’s Church and schools in Highfield, where I was baptized and educated. Anderson also mentions that a list of the ‘Company of Merchants trading to Africa’ included Henry Blundell and his friends, and that Henry Blundell was much concerned about William Roscoe and other abolitionists trying to end the slave trade. So let us look a bit deeper into the Liverpool slave trade.

The first ship weighing 30 tons sailed from Liverpool to Africa in 1709 and the Old Dock was opened in 1715. By 1752 there were 83 vessels in the African slave trade. In 1770 the population of Liverpool had increased to 35,000 and 106 vessels sailed to Africa.

During the 18th century, some 5,000 voyages from Liverpool transported almost one and a half million slaves to the New World. By 1787, thirty seven of the forty one members of Liverpool Council were involved in slavery. Further, all of Liverpool's twenty Mayors who held office between 1787 and 1807 were involved. Liverpool's net proceeds from the African trade in 1783-93 are said to have been £12,294,116, which today would have a relative value of about £400,000,000.

There is much evidence to document deep and lucrative involvement in the slave trade by the Blundells and their partners Thomas Leyland, William Earle, Samuel Warren and Edward Chaffers. Records show that from 1722 to 1784 slave ships owned by the Blundells conducted 113 voyages with 31,341 slaves embarking in West Africa and 25,313 disembarking in the Caribbean. They also dispatched slaves to Chesapeake Bay.

I am not sure if John Clarke, owner of the Winstanley and Orrell colliery and The Walking Horse, was directly involved in the slave trade, but there is no doubt that as a major Liverpool banker he benefited greatly from the slave trade. His father established the first bank in Liverpool in 1774.

I have found no evidence that the Bankes family of Winstanley was directly involved in the slave trade, but there is no doubt they and other landowners benefited greatly from leasing land and mineral rights to Liverpool entrepreneurs, especially John Clarke. In the 19th century, Bankes developed their own colliery and railway, landscaped Winstanley Estate and bought an 80,000 acre estate in Scotland. John Clarke built The Mount on Orrell Road.

Robert Daglish built The Walking Horse and two more early steam locomotives at Haigh Foundry, so it is also important to identify sources of capital for the foundry. There is strong evidence that much of the capital to renovate Haigh Estate and expand the foundry came from the slave trade. When Alexander Lindsay, 6th Earl of Balcarres, took over Haigh Hall it carried a debt of £6,000 and was in terrible condition. The Earl’s salvation came when King George III appointed him Lieutenant Governor of Jamaica ─ the jewel in the imperial crown ─ where he served from 1794 to 1801. There were more than a quarter of a million slaves on the island of Jamaica, where he purchased plantations and employed hundreds of slaves. It is reasonable to assume that he also profited from the sale of sugar and other products from his plantations. Further, he contracted slave-labour for the Army and the civil government in Jamaica. On completing his term as Governor, he received about £65,000. On returning to Haigh, the Earl is reported to have established an ‘Aggrandising Fund’ for the purpose of accumulating wealth for his family and in 1804 he appointed Robert Daglish engineer at Haigh Foundry.

The Slave Trade Act of 1807 abolished the slave trade in the British Empire, but not slavery itself. It was not until 26 years later that slavery was abolished. With the Abolition of Slavery Act of 1833, James Lindsay, the 7th Earl of Balcarres and Baron of Wigan, was paid £14,473.15s.6d compensation for 895 slaves in Jamaica. The Earl built Haigh Hall between 1827 and 1840 to replace the ancient manor house.

Expanding from domestic cotton, flax and wool spinning and weaving prior to 1800, the textile industry in Wigan was rapidly transformed into huge mills with thousands of cotton workers. Two photos of my artwork depict the Wigan cotton mills and workers and remind us that the cotton spun in Wigan mills was grown by slaves, and later by freed slaves in the USA.

Below are additional points of interest.

- People prominent in the Liverpool slave trade and development of Wigan and the Wigan coalfield also held prominent positions in Liverpool. William Blundell, Esq., was Town Clerk in 1662. Thomas Steers, architect of The Douglas navigation, was Mayor in 1739, Henry Blundell Hollinshead was Mayor in 1807 and Magistrate in 1825. Jonathan Blundell Hollinshead was Mayor in 1818 and 1824 and a Magistrate in 1825.

- John Winstanley, Gent., was Town Clerk of Liverpool in 1640 and Henry Winstanley was Bailiff in 1741 and Mayor in 1752.

- Hugh Cowell from Wigan is recorded as the captain of three slaving voyages between 1790 and 1799. His parents were William and Alice (nee Hartley) of Millgate. He was probably baptized in Wigan Parish Church on 6 November 1766.

- Philip Henshall from Leigh was captain of six slaving voyages from 1796 to 1802. He was born on 13 January, 1764 and his father was Jeremy (of Bedford).

- Richard Wilding from Leyland undertook 28 slaving voyages from 1777-1790.

- Edward Cropper (1704-1776) from Ormskirk undertook 34 slaving voyages from 1753 to 1766.

- Meyrick Holme (Bankes) was Squire of Winstanley Hall from 1803 to 1827 and married Maria Elizabeth Langford Brooke of Mere Hall Cheshire. Her family were major slave owners in Antigua.

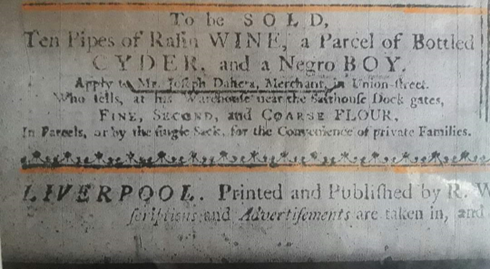

Negro men, women, boys and girls were offered for sale in Liverpool.

- In 1795 Richard Watt purchased Speke Hall for £75,500. Born at Shevington, he arrived in Jamaica in 1744 and partnered in a large scale slave-factorage, managed estates for absentee landlords and purchased privateering and slave ships. He also imported goods such as sugar and rum from Jamaica to Liverpool where he purchased and lived in Oak Hill House. Although he counselled against the excessive punishment of slaves, he invested in slaving voyages and in 1793 purchased a slaving ship and arranged for the trafficking of 549 African slaves to Jamaica. He bought Speke Hall in 1795 and in his 1797 will he left Speke Hall in trust to his nephews Richard Watt and Richard Walker and his kinsman Thomas Watt for the benefit of his grandson Richard Watt.

- The Gerrard family was an ancient family in Ashton in Makerfield, Bryn and Wigan. In 1638, Dr. Thomas Gerrard, a surgeon, arrived in Maryland with five man-servants and became one of the largest landowners in Maryland and Virginia. He was born in New Hall, Ashton-in-Makerfield, in 1608, died in Virginia in 1673 and is buried in Maryland. In his will he mentions many negroes in his possession. The first slaves in the eastern USA were from Angola, transported across the Atlantic in Portuguese boats and captured by English privateers.

- “.. the names of George Thompson and Thomas Gerrard appear on the records as the first owners of that portion of the National City which is colloquially known as “Capitol Hill”. Under the "Conditions of Plantations'' imposed by the Baron of Baltimore under his charter as absolute lord of the domain, Thompson and Gerrard in 1662-3 acquired title to an extensive acreage which now includes all of Capitol Hill, parts of Anacostia and the outlying country and a generous slice of the city proper from about Ninth and K streets northwest to the Potomac where the Bureau of Engraving and Printing has been erected”.

- Textiles and probably metal products from south-west Lancashire, most likely including Wigan, were exported to Africa in Liverpool slave ships.

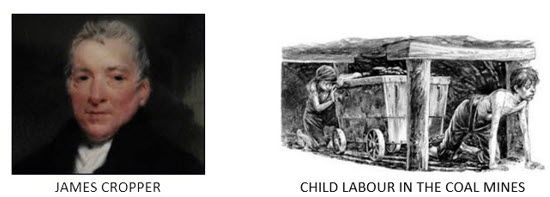

- Many children worked in the Wigan mills and coal mines, and some called them “white slaves”. The Factory Act was passed the same year as the Abolition of Slavery Act in 1833. This Act made it illegal to employ children under nine years of age, but made it legal to employ 9–13-year old children to work up to nine hours a day and 13-18 year old children to work up to 12 hours a day. In 1842 the Mines and Collieries Act removed women from the coalface, but still permitted boys over the age of ten to work underground. Only in 1870, with passage of the Education Act, did it become mandatory for all under the age 14 to attend school full time.

Not everybody was in favour of the slave trade. Wigan Dissenters sent several petitions to the 1830 Parliament for the abolition of slavery and James Cropper (1773-1840), a Quaker born in Winstanley, in Spring Pool up by the Big Stone, played a prominent role in the abolition of slavery. Cropper served as Chairman of the Liverpool Anti-Slavery Society and his female relatives played central roles. William Roscoe, a partner of John Clarke, Thomas Leyland and the Earles, also was a strong advocate for the abolition of slavery.

Social morals have changed over time, but black, and some would also say white, slaves are woven into the history and development of Wigan and many other towns and cities. Many human beings were exploited and suffered, while others benefited.

Derek Winstanley 2023

REFERENCES

D. Alvarado, R. Crick and E. Figueroa, Jr., The application of field geophysics for reconnaissance of a Jamaican slave village and the surrounding area (http://keckgeology.org/files/pdf/symvol/13th/Jamaica/alvarado_et_al.pdf).

D. Anderson, The Orrell Coalfield, Lancashire 1740-1850, Moorland Publishing Co., Buxton, 1975.

D. Anderson, Blundell’s Collieries 1776-1966, Wigan Printing, Wigan, 1986.

D. Anderson and A. A. France, Wigan Coal and Iron, Smiths Books, Wigan, 1994.

BBC-Cumbria-Abolition-The people trying to abolish the slave trade.

S.D. Behrendt, The Captains of the British Slave Trade from 1785 to 1807, Hist, Soc. Lancs, Chesh, 140, 79-140, 1990.

A. Birch, The Haigh Ironworks 1789-1856; a nobleman's enterprise during the industrial revolution, Bull. John Rylands Lib. 35 (1953), 316-34.

Jonathan Blundell (1751–1800), Trustee of the Liverpool Blue Coat School | Art UK.

G.T.O. Bridgeman, The History of the Church & Manor of Wigan, printed for the Chetham Society, Vol. 15, 1888.

British Banking History Society, Leyland and Bullins (http://www.banking-history.co.uk/leyland.html).

Centre for the Studies of the Legacies of British Slavery, Richard Watt I, of Jamaica and Oak Hill (Legacies of British Slavery (www.ucl.ac.uk).

Child Labour – Industrial Revolution (weebly.com).

R. Daglish, A Yorkshire Horse, J. Railway and Canal Hist. Soc. 31(3), (1993), 123-31.

M.B. Downing, The Earliest Proprietors of Capitol Hill, Records of the Columbia Historical Society, Washington, D.C. , 1918, Vol. 21 (1918), pp. 1-23 Published by: Historical Society of Washington, D.C. (https://www.jstor.org/stable/40067098).

Early Colonial Settlers of Southern Maryland and Virginia’s Northern Neck Counties, (https://www.colonial-settlers-md-va.us).

Fisher, D.R. (ed.), 2009. Wigan Borough, The History of parliament: 1820-1832, Cambridge University Press (http://www.historyofparliamentonline.org/volume/1820-1832/constituencies/wigan).

M. Fletcher, The Making of Wigan, Wharncliffe Books, Barnsley, 2005

S. S. Friedman, Jews and the American slave trade, Transaction Publishers, New Brunswick, New Jersey, 1998.

Gore’s Liverpool Directory, 1825.

J. Hannavy, Historic Wigan, Carnegie Publishing Ltd., Preston, 1990.

J. Hughes, Liverpool Banks & Bankers, 1760-1837, Henry Young and Sons, London, 1906.

International Slavery Museum, European Profits (http://www.liverpoolmuseums.org.uk/ism/slavery/europe/profits.aspx.)

A.P. Kup, Alexander Lindsay, 6th Earl of Balcarres, Lieutenant Governor of Jamaica 1794-1801 (https://www.escholar.manchester.ac.uk/api/datastream?publicationPid=uk-ac-man-scw:1m2767&datastreamId=POST-PEER-REVIEW-PUBLISHERS-DOCUMENT.PDF).

James Lindsay, 24th Earl of Crawford (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/James_Lindsay,_24th_Earl_of_Crawford).

J. Langton, Geographical Change and Industrial revolution: Coalmining in South West Lancashire 1590-1799, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1979.

Lawrence H. Officer and Samuel H. Williamson, Five Ways to Compute the Relative Value of a UK Pound Amount, 1270 to Present, MeasuringWorth, 2013 (http://www.measuringworth.com/index.php).

Liverpool newspapers.

Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Vol. 13, James Cropper (http://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Cropper,_James_(DNB00)).

U. B. Phillips, American Negro Slavery, D. Appleton and Company, New York and London, 1918 .

Refford, B.W., The Bonds of Trade: Liverpool Slave Traders, 1695-1775, (https://www.academia.edu/604769).

Richardson, David; Schwarz, Suzanne and Tibbles, Anthony (Eds.), Liverpool and Transatlantic Slavery, Liverpool University Press, 2007, 315 pp.

D. Sinclair, The History of Wigan, Wall, Printer and Publisher, Wigan, 1882

L. Turnbull, The Montagu Family of East Denton Hall (http://www.mininginstitute.org.uk/papers/TurnbullMontagu.html).

L. Turnbull, personal contact 8 March 2012.

University College London, Department of History, 2013, Legacies of British Slave-ownership (/lbs/) (http://www.ucl.ac.uk/lbs/).

L. S. Walsh, Liverpool’s Slave Trade to the Colonial Chesapeake: Slaving on the Periphery (http://www.hslc.org.uk/downloads/walsh_paper.pdf).

Wikipedia, Breaking the Silence: Slave Routes (http://old.antislavery.org/breakingthesilence/ slave routes/slave_routes_unitedkingdom.shtml).

Wikipedia, International Slavery Museum (http://www.liverpoolmuseums.org.uk/ism/about/).

E. E. Williams, Capitalism and Slavery, University of North Carolina Press, 1944.

G. Williams, History of the Liverpool Privateers and Letters of Marque with an Account of the Liverpool Slave Trade, William Heinemann, Liverpool, 1897.

D. Winstanley, The Evolution of Early Railways in Winstanley, Orrell and Pemberton, Lancashire, England, 177s to 1870s, Early Railways, Papers from the Fifth International Early Railway Conference, Caernarfon, June 2012 (ed. David Gwyn), Six Martlets Publishing, Suffolk, UK, 2014, 112-131.

D. Winstanley, Wigan and the Slave Trade. Past Forward, Wigan, 70, Aug-Nov 2015, pp.24-25.