Rylands Sidings

RYLANDS SIDINGS

Introduction

Reminiscences of Rylands Sidings at Whitley from sixty years ago, the association with a cotton magnate and their place in the war time history and industrial heritage of Wigan.

A Schoolboy’s dream

In the late 1950’s, in the school holidays or at weekends my mother would send me on an errand that I absolutely loved doing. My grandfather James Prescott worked in the Rylands Sidings signal box on the main London to Glasgow railway line at the rear of Beech Hill Royal Ordnance Factory (ROF). Mum would send me over with lunch she had prepared for him, or his evening meal if he was working late.

It was only a 10 minute walk from our house in Wellfield Road via Fir Grove, Gidlow Lane and Dawson Avenue. After following the Beggars Walk footpath round the back of the factory I would go through the kissing gate, down a flight of steps and wait patiently at Whitley foot crossing until a window opened at the front of the box and a hand would appear indicating that it was safe to cross the line. Woe betide me if I ever crossed without permission.

Foot Crossing with Scouts Hill in the background.Little did he know that when he wasn’t on duty me and my friends train spotted at the crossing. When we were bored we would place pennies on the line to be flattened by train wheels or put our ears to the rail listening for approaching trains. We also played football or cricket in a field near Cub’s Hill which we knew as Daisy Pitch, from which we could keep an eye on the main line.

Foot Crossing with Scouts Hill in the background.Little did he know that when he wasn’t on duty me and my friends train spotted at the crossing. When we were bored we would place pennies on the line to be flattened by train wheels or put our ears to the rail listening for approaching trains. We also played football or cricket in a field near Cub’s Hill which we knew as Daisy Pitch, from which we could keep an eye on the main line.

On the other side of the railway there was a rope swing on a tree at the side of Barley Brook which ran through a culvert under the lines. Nearby was Scout's Hill which was in fact the spoil from Elms Colliery, as was Cub's Hill on the other side of the line, now nature had taken over and it was covered with trees.

The Ordnance Survey (OS) map of Wigan revised in 1927 to 1928 shows that the area near Whitley Hall Farm, between the railway and present day Whitley Crescent was Whitley Park Golf Course. Its clubhouse was accessed via a track from present day St. Clements Road. The OS map revised in 1948 shows that a sports ground had been developed to the north of Scouts Hill adjacent to Old Lane. It included a pavilion, football pitch and also tennis courts on the top of Scout's Hill.

Grandad had worked on the railways all his life, firstly on the locomotives as a fireman then eventually becoming a signalman. During the Second World War he combined his job on the railways with being a member of the Home Guard. He worked in many signal boxes in the area, from Culcheth and Golborne to the south of Wigan to Boar's Head and Standish Junction in the north.

For a young lad who loved steam trains, to be allowed into a working signal box was a dream come true. The box was a two storey Victorian type, with the top half of timber sat on a brick base, a privy accessed from inside was attached to the side as though hanging in mid-air. The lower storey, known as the locking room, was occupied by the lower part of the lever frame, with the rodding and wires to control points and signals exiting through a gap in the front wall.

Rylands Siding Signal Box

Rylands Siding Signal Box

I would climb the steep wooden steps with hand rails either side and open the door to a world that hadn’t changed for decades. Inside everything was immaculately clean and tidy. There was a combined smell of paraffin oil, Brasso and floor-polish generated by the warmth of the cast iron potbellied stove which sat on the wooden floorboards, it's chimney disappearing through the roof. An old aluminium kettle sat on top and a coal scuttle to one side.

On the far wall was a tall writing desk, the train movements register on top and a stool in front. Above it was large round clock with Roman numerals and LMS (London, Midland & Scottish) printed on the face. To the side was the bell operated telegraph signalling system, a telephone, and a notice board. A wooden chair with a cushion on nestled in the corner and under the sash windows facing the railway lines was a bank of 30 shiny levers painted red, blue, white, and yellow that operated the points and signals. Above them was a large diagram board showing the layout of the lines and points. There were two semaphore signal gantries guarding the sidings, one just south of the box, the other to the north of the foot crossing.  Rylands Sidings in the 1960's

Rylands Sidings in the 1960's

I was fascinated with the workings of the box so he taught me how the block system worked and how signal boxes communicated with each other. A bell ringing from up the line with a 1-2-1 beat indicated ‘train approaching’. He would always acknowledge the train crew with a wave.

When the shunters were busy bringing in the wagons from Gidlow coal washing plant or trains arrived to take full wagons away I would help him pull the levers to change the points. First a rag would have to be wrapped round the shiny metal tops of the levers to prevent them becoming tarnished and rusty from sweaty hands.

"Lindsay" at John Pit engine shed

"Lindsay" at John Pit engine shed

The most famous of these little shunters was the 0-6-0 saddle tank Lindsay, built in 1887 at the Wigan Coal & Iron Company's Kirkless workshops. it was reputed to have been named after the eighth Earl of Balcarres, Alexander Lindsay. In 1947 it came under the ownership of the National Coal Board. Between 1949 and 1954 it was observed working in the Westhoughton and Atherton areas. In the 1950’s and early 60’s it was working round the Standish area shunting coal wagons to Rylands Sidings.

After a spell at Chisnall Hall Colliery in Coppull and at Hafod Colliery near Wrexham Lindsay was sold to Maudland's scrapyard in Preston. In 1976 it was bought by the Lindsay Trust and restored at Steamtown in Carnforth where it again came under steam in 1981.

"Lindsay" restored

"Lindsay" restored

Following the closure of Steamtown in 1998 Lindsay was put in storage. In 2019 its new owner moved it to a private site for restoration, it is the only surviving Wigan built locomotive.

The Coming of the Railways

In 1830 the railway line between Manchester and Liverpool was opened, starting the expansion of the railway system in the country. The railways came to town on 3 September 1832 when the Wigan Branch Railway was opened, connecting Wigan to the Liverpool to Manchester Railway at Parkside, near Newton Le Willows. Wigan’s first station was located near Chapel Lane and was simply called Wigan Station. On 31 October 1838, the North Union Railway opened between Preston and Wigan and connected with the line from Parkside. Wigan Station then relocated from Chapel Lane to its present location in Wallgate.

There were numerous pits to the north and west of Wigan, and originally coal was hauled to its destination by horse and cart. Then the tram road or tramway system was introduced, which transported coal from the pit head in tubs on narrow gauge rails to be loaded on to barges on the canal.

Depending on the topography of the land various methods were employed. Some collieries used gravity, on tram roads with inclines a man would ride on the tubs and use a brake to slow down, the tub would be towing a carriage carrying a horse, which would then be used to pull the empty tub back up the slope.

Peculiar to the Wigan area was the endless rope system No. 2 which used two sets of rails. A steel cable was coiled around a pulley in the engine house and one at the terminus at the canal and would be moving continuously two or three miles per hour. The full tubs were attached to the endless rope with rope clips at the pit head and unhooked at the far end to be emptied. The empty tubs were hooked on the rope which then came back to the pit on the other set of rails.

With the railway passing close by new opportunities opened up for the colliery owners to transport their coal more efficiently. They signed private sidings agreements with the North Union Railway and soon standard gauge mineral branch lines were connected from the pit head to the main railway line.

Between 1842 and 1845 a branch line was constructed that left the North Union line at a point known as Turners Siding, approximately where the present day Spencer Road bridge is. It looped round to the east and onto Holme House Colliery, which was located in today's Holme Avenue to the rear of Wigan Infirmary. The Colliery at the time was run by Henry Woods who also owned Holmes House Foundry, he was also involved in the textile trade at Trencherfield Mill. The pit was named after nearby Holme House, a large dwelling in its own ground, the Brocket Arms Hotel now sits on the site of the house at the junction of Mesnes Road and Holme Terrace. The colliery had several owners before closing in 1887 and the following year the branch line to the North Union line at Whitley was taken out.

Rylands Sidings

Rylands Sidings was named after Rylands & Sons who opened their first cotton mill, Wigan Linen Works on land they had purchased off Gidlow Lane in 1824. Under the guidance of John Rylands the firm prospered and became the largest textile manufacturers in the country. In 1834 following a string of personal tragedies, in which four of his children died within four years of each other, all at an early age, John Rylands left Wigan to live in Ardwick Green in Manchester. He became Manchester's first multi-millionaire and on his death in 1888 he was proclaimed the 'King of Cotton'.

After finding valuable coal reserves on their land in Wigan the Rylands family became colliery masters and opened a number of pits under the name of Gidlow and Swinley Colliery.

Rylands Mill Railway Sidings

Rylands Mill Railway Sidings

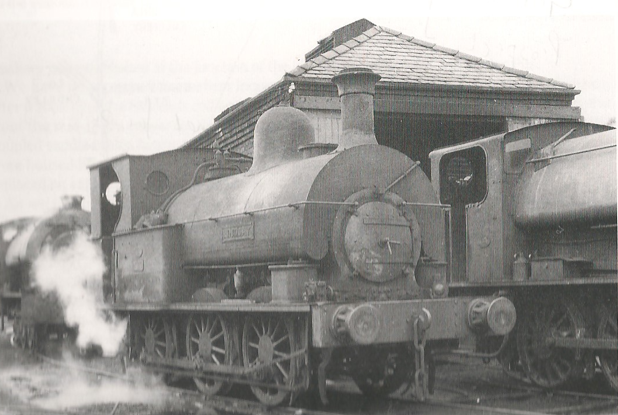

Originally coal was transported from the pit heads by tramroads but with the coming of the railways Rylands came to a private sidings agreement with the North Union Railway. They funded a standard gauge private branch line, nearly a mile in length that ran from the collieries located off the present day Walkden Avenue, under the railway bridge at Buckley Street, before looping round the lodge that supplied water to the original mill and on up to Rylands Sidings at Whitley.

In 1867 a new purpose built mill was opened on land to the east of the North Union line, known locally as Rylands Mill, Gidlow Mills or on ordnance survey maps as Gidlow Works. Two more branch lines were added going directly to the factory. Rylands Collieries ceased coal production in 1897, bringing an end to the firms sixty seven year connection to the Wigan coalfield.

Map showing Whitley Sidings and mineral lines

Map showing Whitley Sidings and mineral lines

The northern end of the sidings at Whitley was connected to a private mineral railway first developed by the Standish Railway Company, before being taken over by Wigan Coal & Iron Company. In its heyday the sidings was a very busy place with coal being transported from Giants Hall Pit, Gidlow Pit, Swire Pit and Prospect Pit in Standish, as well as Taylor Pit and John Pit in Standish Lower Ground.

Incidents and Accidents

Over the years Rylands sidings have been the scene of numerous incidents and accidents. They were also a notorious black spot for suicides. One strange case was a man named Roger Field from Whelley. In 1880 he became mentally deranged suffering from religious delusions and so was committed to Whittingham Asylum in Preston. Soon after he went missing but was found three hours later hiding in a coffin in the stores.

The following year he was allowed to work in the garden but promptly disappeared from the institution. At quarter past ten the following evening he turned up at a points man’s cabin at Rylands Sidings asking for a drink of water. After the workman gave him some cold tea he set off in the direction of Wigan. The next morning a report was made to the police that a man’s body had been seen on the track. On investigation they found Field’s decapitated body just south of the signal box, he had been struck by the night mail train.

On 25 October 1867 there was a fatal accident at the sidings. At quarter past two in the afternoon a train arrived from Edge Hill in Liverpool with empty wagons, their instruction was to leave them in the sidings and take loaded ones out. As the train pulled up at the points the brakesman, 28 years old Michael Dowling got out of his van and kneeling on the buffer of the van and the buffer of the wagon next to it started unhooking the van from the train. Unaware of this the engine driver started moving again causing Dowling to fall on to the rail. The detached brakevan carried on moving under its own velocity and one wheel passed over the unfortunate man’s body. He was taken to Wigan and attended by a doctor but died at twenty to eight in the evening.

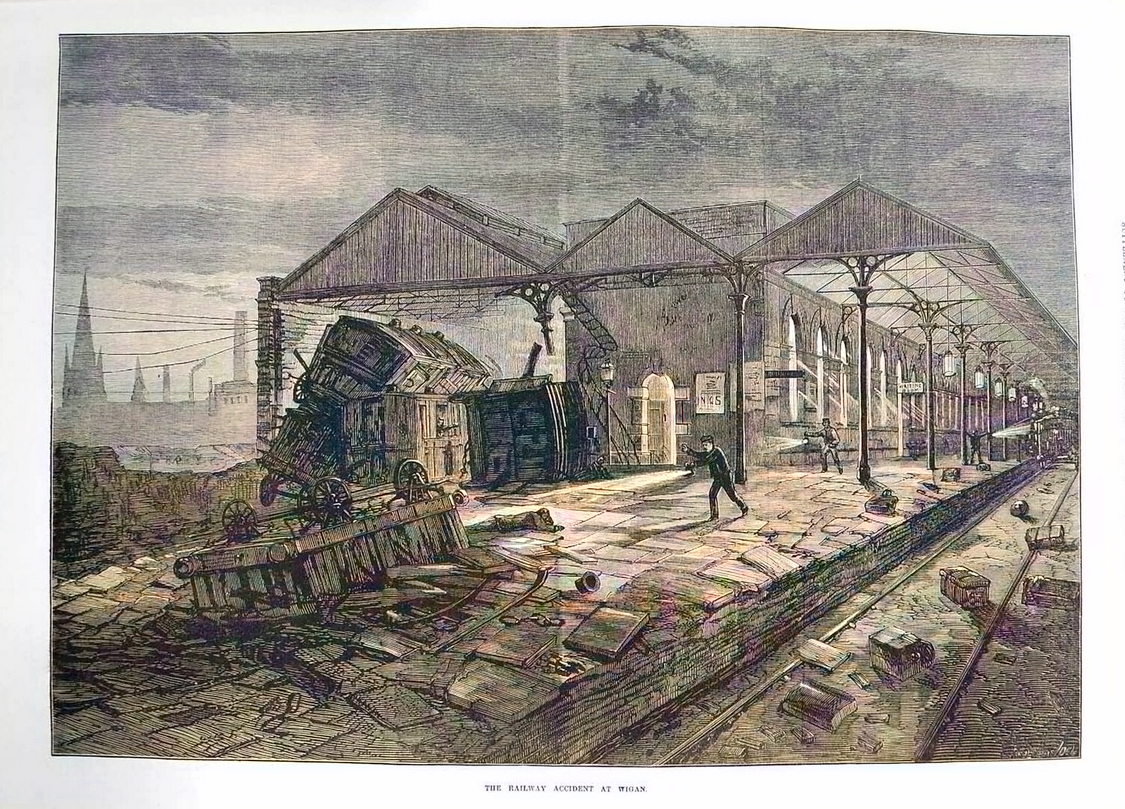

The worst railway accident in Wigan's history occurred in the early hours of Sunday 3 August 1873. The Scotch Express consisting of two engines, twenty two carriages and three vans had left Euston Station in London at five minutes past eight the previous evening bound for Perth. Many of the passengers were upper class aristocrats travelling to Scotland for the opening of the grouse season. It was fifteen minutes late as it neared Wigan and was travelling at 40 miles per hour.

Railway Accident at Wigan in 1873

Railway Accident at Wigan in 1873

The two engines and fifteen of the carriages passed through the station safely. However two wheels of the sixteenth carriage derailed at a set of facing points which led to the loop line siding on the other side of the main platform. Next came a luggage van which derailed completely, demolishing a lineside shunters cabin in the process. The couplings held on these two vehicles and they travelled the length of the platform before being put back on the rails by a crossing at the north end of the platform. The remaining seven carriages and the rear guards van derailed and became detached from the rest of the train and travelled along the siding for fifty or sixty yards.

They then smashed in to the platform, the leading carriage was thrown up into the air, overturned and landed on the platform wheels uppermost. Four bodies were later extricated from underneath the wreckage. Two other carriages left the rails and were smashed on the side walls of the platform. Two more carriages overturned in the sidings and were wrecked. Only one of the carriages and the guards van were undamaged.

Travelling in one of the first class carriages was Scottish born Mr. Andrew Wark, a stockbroker of Old Hall, Highgate, London. He was accompanied by his wife, four children, a governess and two nurses. Three of the children were killed along with one of the nurses. Mrs. Wark suffered a broken leg and her surviving child a broken thigh. Mr. Wark, the governess and the other nurse escaped with bruises.

To the west of the siding a brick wall was knocked down, the debris falling in to Queen Street twenty or thirty feet below the level of the railway. The roof of one of the carriages was hurled over the wall and through the slated roof of Walkers Foundry, carrying with it a Mrs. Roberts. Her mutilated body was found in the foundry, a number of men working close by escaped injury.

The front portion of the train came to a halt at Rylands Sidings after the driver looked behind and saw sparks and flying debris. He then communicated with the signalman on duty at the box to await further instructions. Ninety minutes after the disaster the Scotch Express was given clearance to continue on its journey to Scotland.

In total thirteen people died and thirty were injured. The inquest was held by the Borough Coroner Ralph Darlington Esq who lived at Springfield Hall. A board of Trade investigated headed by Captain W. A. Tyler concluded that the primary cause of the accident was excessive speed. No faults were found with the offending points which were undamaged. However as a recommendation an extra locking tie bar, known as a switch lock, was added to every set of points on the rail network so as to increase strength and stability. A design modification which remains today in current points on the national rail network.

Another incident involving the Scotch Express happened on 14 November 1878. The train consisting of four carriages, a mail van and a guard’s van had left London at 7am and passed through Wigan at noon. As it approached Rylands Sidings the crank axle of the engine broke throwing the carriages off the rails. Luckily they stayed upright as they ploughed up the permanent way. Despite the train crew and passengers being severely shaken up there were no serious injuries. An approaching train heading south was stopped in time before reaching the sidings.

About five o’clock on the morning of Friday 15 September 1882 a mixed coal and goods train left Springs Branch heading north. At Rylands Sidings it was signalled to stop. There was dense fog prevailing at the time and for the fear of being run into by a train coming in the same direction the brakesman Robert Cowan left his van and proceeded back down the line to place fog signals on the rails to warn drivers of the stationary train.

Not knowing that Cowan had left his van the driver moved off leaving the brakeman behind. Cowan went to the signalman at Rylands Siding and asked him to telegraph Boars Head signal box to stop the train there. On reaching Boars Head the train was halted while it waited for Cowan to catch up. Unfortunately the line at this point was on an incline and there was severe pressure on the engine, there being no brakes applied on the van.

Eventually a coupling ten lengths from the rear of the train snapped, and the rear portion train made off, gradually gaining speed as it passed down the gradient. Cowan met the train but was unable to get into the van to apply the brake. The train ran on through Rylands Sidings and Turners Siding and into Wigan station where it collided with a stationary train hauling empty coal wagons, slightly injuring the brakeman William Clarke. The rear two wagons of the runaway train, one containing furniture and the other coal were completely smashed.

Industrial Decline in the 20th Century

The North Union Railway was acquired by the Grand Junction Railway which in turn was taken over by the London, Midland & Scottish Railways (LMS) in 1923. The same year Walkden Avenue was extended to meet with Buckley Street. This linked Gidlow Lane with Mesnes Road and now meant that through road traffic would be using Buckley Street bridge as well as industrial locomotives toing and froing between the sidings and Rylands factory. Two flag men, who operated from a little cabin at the side of Buckley Street bridge were employed to control traffic when the shunters were working across the road.

Buckley Street Railway Bridge

Buckley Street Railway Bridge

In 1939 ROF No. 15 was opened in Beech Hill and was tasked with the production of artillery shells. A spur from the Giants Hall pit mineral line was taken into the factory in February 1940 for the transportation of munitions via Rylands sidings to the ROF filling factories at Chorley and Risley. The factory had its own shunter, a diesel that arrived new from the Hunslet Engine Company of Leeds. After the war, the factory was kept open for the peacetime production of armaments but was eventually closed in 1958. It was taken over by the American firm Tupperware who discontinued the use of the railway sidings, then in 2003 its present owners Milliken Industries moved in.

The coal industry was nationalised on 1 January 1947, becoming the National Coal Board (NCB). Soon after nationalisation a new coal washery was built near to the site of Gidlow Pit to replace the earlier plant near John Pit. Gradually the pits closed and by the late 1950's only Giants Hall Colliery and Standish Hall and Robin Hill drift mines which had been opened in 1946 and 1952 respectively remained.

Gidlow Coal WasherIn 1948 the country's railway network was nationalised and became known as British Railways (BR), later rebranded as just British Rail. The original LMS line from London to Glasgow became known as the West Coast Main Line.

Gidlow Coal WasherIn 1948 the country's railway network was nationalised and became known as British Railways (BR), later rebranded as just British Rail. The original LMS line from London to Glasgow became known as the West Coast Main Line.

In 1954 textile production ceased at Rylands Mill and the premises were transferred to Great Universal Stores Ltd for use as a mail order warehouse by its subsidiary John England. It is not known if rail traffic ceased when Rylands & Sons Ltd moved out or whether the sidings were retained for mail order traffic. Certainly, it had ended by the mid 1960’s as the Line Plan shows that the private sidings agreement to the factory was terminated on 30 September 1966.

The Latter Days

Finally Giant's Hall Colliery, the last remaining vertical shaft mine in the area closed in 1961, followed by the Robin Hill and Standish Hall drift mines in 1963 and 1965 respectively. Rylands Sidings were now redundant, except for parking by engineering trains. In 1964 my grandfather moved from Rylands Sidings to Wallgate signal box. He sadly died in 1966 during the last days of the steam era.

With the closure of the pits and Rylands Mill and railway signalling now converted to electric controlled by Warrington power box there was no further need for Rylands Sidings signal box. It finally closed on 1 October 1972 and was demolished. The Whitley foot crossing that took the ancient Beggars Walk footpath across the main line was replaced by a new overbridge a short distance away in 2000.

Graham Taylor July 2022