The War Diary of Rifleman William Walls of Abram

1915-1919

Introduction

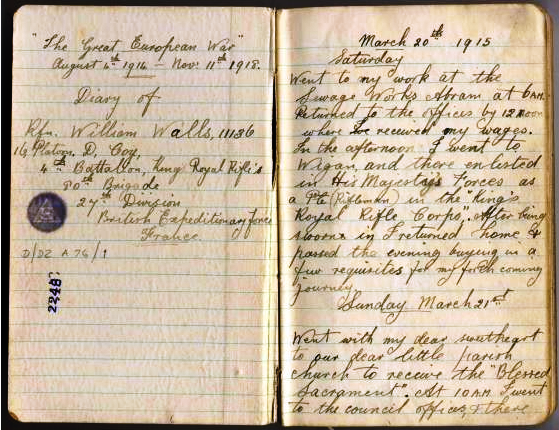

The World War One diary of William Walls of Abram has been transcribed by Wigan Archives volunteer Susan Berry. There are two volumes, and the transcribed version is 228 pages long. It is rare to come across a diary written by a private soldier that covers his whole wartime career, in this case between March 1915 and February 1919.

Page from the Diary

The ordinary soldier wasn’t usually privy to the big picture and rarely knew of events that went on outside of his own unit. He was more concerned on a daily basis with his own personal survival and well being and that of his comrades. As well as accounts of being in the trenches and in action on the front-line, William describes his spells in hospital and records the more mundane activities of military life back in the rear areas.

Reading his diary reveals the things that William treasured the most and kept him going during his long absence from Abram in the Great War. These were his religious faith, his letters from home, especially the ones from his sweetheart Annie, and his passion for football.

This summary of the diary will help to put it in its historical and social context and clarify the military situation that William found himself in the First World War.

Abram Village

William Walls was born on 28 January 1892 at 428 Warrington Road, Abram and baptised three months later, on 24 April by Rev Hewitt Linton at St. John’s CE church. He was the youngest of nine children, six boys and three girls but two of his brothers, his namesake William and Harry had sadly died in infancy before he was born.

Warrington Road, Abram

The relationship of his parents William Walls Snr who hailed from Darwen near Blackburn and local girl Mary Livesey had got off to a rocky start. They had had a baby girl born out of wedlock in 1871 and Mary named her Annie Walls Livesey using William’s surname as the child’s middle name. Circumstances changed however and William and Mary finally married two years later in April 1873 at St. John’s church.

William Jnr was eight years old when his coal miner father died in 1900, aged 54. The following year the 1901 census taken on 31 March shows the Walls family had moved the short distance from 428 to 448 Warrington Road. William’s eldest sibling Annie had by this time married and was also residing at No. 448 with her husband Thomas Crouchley and their one-year-old son Harry.

William was a deeply religious person, being confirmed on 18 May 1907 at St. John’s by Bishop Chavasse of Liverpool. He attended church regularly for Holy Communion and as well as being a member of the choir he was later to become a Sunday School teacher at the Good Shepherd Mission Room at Lily Lane in Bamfurlong.

At 4pm on the afternoon of Tues 18 August 1908, sixteen-year-old William finished his shift underground at nearby Maypole Colliery in Park Lane and walked the short distance to his home in Warrington Road. Just over an hour later at 5.10pm an explosion ripped through the pit killing 76 miners. ‘Lady Luck’ was shining on William that day as she was to do so all through the Great War.

Statistics from the 1911 census show that the population of Abram was 6,893, residing in 1,364 households and of those, 1,005 people worked in the mining industry in Abram and the surrounding areas with 145 being employed in the cotton mills.

The village had a very diverse population. As well as residents having been born in all parts of Lancashire, 492 residents were born outside the County. They came to live in Abram from 24 different English Counties, mainly from Staffordshire, Shropshire, Cheshire and Yorkshire but also the Isle of Wight, Wales, Ireland, Scotland and as far afield as America and Canada.

The much loved and respected Vicar of St. John’s who went by the grand name of Rev Thomas Frederick Brownbill Twemlow had been born in Manchester, his wife Mabel came from Hereford.

Church Sexton and school caretaker Arthur Coultas was born in Leeds, his wife in Upper Gornal, Staffordshire. They lived at 174 Warrington Road with their three children and a servant, Ellen Evans who hailed from Keele in Staffordshire.

The village’s medical practitioner, Andrew Occleshaw Bentham (who by chance is distantly related to the author) lived at Springfield House on Warrington Road and was born in High Street, Standish, his wife Elizabeth was a Chorley girl.

The Matron of Abram Sanatorium in Park Lane was Annie Mead who hailed from Harwich in Essex. The only patient at the time was six-year-old John Maddison from Haydock.

The Manageress of the Bucks Head Hotel was Annie Melrose Edwards who hailed from Carfrae, a village in Berwickshire in the Scottish Borders. Annie was a widow and had moved to Abram with her three young sons from Macclesfield in Cheshire, where she had been a Publican.

Station Master, Septimus Smith lived at 80 Bickershaw Lane and came from Retford in Nottinghamshire, his wife Alice was born in Kirton Lindsey in Lincolnshire.

The Headmaster of the Elementary School was 56-year-old George Winfield from Weaverham in Cheshire. He lived at 333 Warrington Road with his wife Mary and three children.

The head mistress of the Infants Day School was Alice Davies from Walkden and lived at 432 Warrington Road with her widowed stepmother Margery.

Forty-two-year-old Police Sgt Robert Gordon came from Kincardinshire in Scotland, as did his wife Jane. They lived at 497 Warrington Road with their two daughters who had both been born in Colne in Lancashire.

Widow Abigail Scott aged 70 who farmed Fields Farm in Lee Lane was born in Bewcastle near Carlisle, as was her son, her two daughters were born in Rainhill near St. Helens.

Sixty-five-year-old John Garvin, a retired miner living at 91 Warrington Road had been born in the USA, his wife Mary Ann came from Frome in Somerset and their eldest son Henry had been born in Wales. Living with them was their niece Grace Parker, born in Blackheath, Middlesex.

The grocer’s shop at 46 Warrington Road was run by widow Alice Barton from Wigan. Lodging with Alice was gardener Albert Morris aged 26, from Montgomeryshire in Wales.

Also living with Alice at the shop was Elizabeth Ann Harrison and her two-year-old son Thomas. Elizabeth, who had been born in Hindley had been widowed at the age of nineteen when her husband Thomas was killed in the Maypole Pit disaster. She was five months pregnant at the time and her husband never got to see his son. Elizabeth was being financially supported with a pension from the Maypole Colliery Fund.

By the time of the 1911 census William Walls was still living at 448 Warrington Road with his mother and siblings. Along with his brothers Bob and Jim, he was working underground in the pit as a haulage hand, but he was soon to leave for a career in the water industry. His sisters Betsy and Maggie were both cotton weavers. His eldest sister Annie was still living there with her children Henry and Nellie but had separated from her husband Thomas. Elder brother George, also a miner, had married Mary Ellen Unsworth who hailed from Golborne and was now living across the road from his old home at 517 Warrington Road.

Young William Walls

At the outbreak of WW1 William was courting a girl named Annie Lowe, originally from Ashton in Makerfield but on the 1911 census was living at 160 Warrington Road, opposite Lee Lane. Annie and her three sisters, Mabel, Hilda and Mary worked in a cotton mill; their father James was a Colliery Loco driver.

For King & Country

With the First World War just eight months old, William made his first entry in his diary on Sat 20 March 1915:

“Went to my work at the Sewerage Works Abram at 6AM. Returned to the offices by 12 Noon where I received my wages. In the afternoon I went to Wigan and there enlisted in His Majesty’s Forces as a Pte (Rifleman) in the King’s Royal Rifle Corps. After being sworn in I returned home & passed the evening buying in a few requisites for the forthcoming journey”.

Two days later recruit No. R11136 Rifleman Walls travelled by train down to the Rifle Corps Infantry Depot at Peninsular Barracks in Winchester, Hampshire. He was accompanied by another Wiganer from Manor St in Newtown by the name of Bill Battersby, who had enlisted at the same time.

Rifleman Walls - Kings Royal Rifle Corps

On the completion of their basic recruit training, he and his fellow recruits moved from Winchester to the Isle of Sheppey in Kent for more military instruction. In early July with training completed William was granted four days home embarkation leave.

On 21 July 1915 as part of a troop replacement draft, he boarded the SS Princess Victoria at Southampton bound for Le Havre. Early next morning William set foot on French soil for the first time and entered the Theatre of War on the Western Front.

At the Infantry Base Depot in Rouen, he was posted to the 4th Bn King's Royal Rifle Corps who were in 80th Brigade, of the 27th Infantry Division. The other units in 80 Bde were 2nd Bn Rifle Bde, 2nd Bn King's Shropshire Light Infantry and 3rd Bn King's Royal Rifle Corps.

After a day’s train ride William finally joined his unit at Erquinghem-Lys near Armentieres on the Belgian border where his new unit was resting for two weeks out of the line. On the journey he had met up with Joe Ward who came from Dudley in the Midlands, they were to become best friends, and both were allotted to 16 Platoon of 'D' Company.

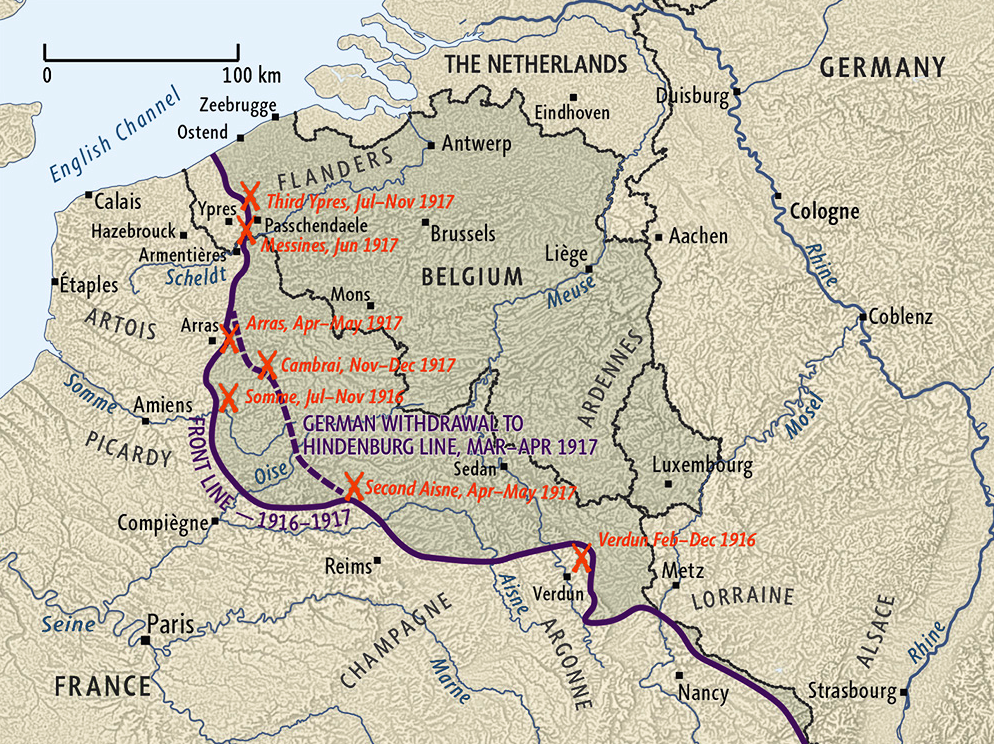

A map of the Western Front

William experienced trench warfare for the first time on 9 August when his unit relieved their sister Battalion 3 KRRC in the front line near Armentieres. Luckily it was a quiet sector of the front at the time with little activity from both sides.

It rained heavily for the first two days and the conditions made movement up the communication trenches very difficult, at one time collapsing a trench. The Bn War Diary records that on the 10th, HE shells bursting over the trenches wounded three men and on the same day a soldier negligently discharged his rifle, killing a Rifleman and wounding a L/Cpl. After a week in the trenches, they were relieved and moved into support at L’Armee from where they once again relieved the 3rd Bn in the Front-Line trenches.

On 30 August the Battalion moved back to bivouacs in Erquinghem-Lys as Divisional Reserve. Two weeks later they marched 12 miles to Strazeele to join up with the rest of 80th Bde. Then on 18 Sept marched to Hazebrouck where they entrained for the 75-mile journey south to the Somme Valley, eventually moving into billets at Cappy on the 21st.

For the next month or so 4 Bn KRRC moved up and down the Somme Valley area and occupied trenches in Frise, Eclusier-Vaux and Morcourt, resting out of the line in huts in Froissy, Bray-Sur-Somme and Cappy. On 25 October 27th Div handed their positions over to the French and the next day started a three-day march through the city of Amiens to Revelles.

At Revelles, William’s and his comrades' curiosity were aroused, as he notes in his diary, when for the next couple of weeks, they practiced a new form of training, instead of trench warfare it was open field work and they also practiced loading supplies on to mules.

The Salonika Campaign

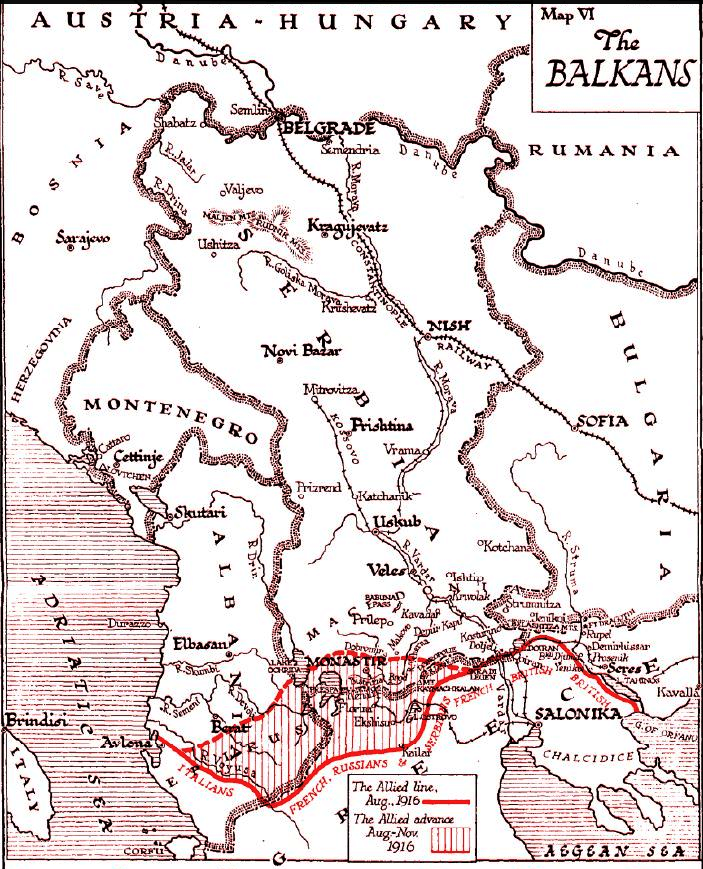

On 28 June 1914 Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria, the ruler of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and his wife Sophie were assassinated in Sarajevo by a Bosnian Serb nationalist by the name of Gavrilo Princip. This act was to ultimately lead to the carnage of the First World War and the loss of millions of lives. As a punishment Austria and Hungary declared war on Serbia and attempted an invasion but this was successfully resisted by the Serbian Army.

Fifteen months later, on 6 October 1915 a second attack under German control took place against the Serbs. Soon after Bulgaria, an old enemy of Serbia allied itself to the Central Powers of Austria, Hungary, Germany and Turkey and declared war on Serbia who was allied to the Western Powers.

In response a multi-National Force was formed to aid Serbia. This diverse force consisting of French, British, Greek, Italian and Russian troops came under the command of French General Maurice Sarrail and numbered 600,000 men at its peak.

However, the intervention of the Allies came too late to save the Serbs from invasion by the Central Powers. The remnants of the Serbian Army were forced to retire through the mountains of Montenegro to Albania losing over 70,000 men in the winter snow. 140,000 civilians also perished of starvation or disease during the ‘Great Retreat’.

The Balkans

The Balkans

William’s Division, the 27th was ordered to relocate to the Balkans to reinforce the British Salonika Force. The BSF which would eventually number over a quarter of a million men had colonial troops from India, Africa and Indo China and volunteer units from Australia, New Zealand, Canada and Malta under its command.

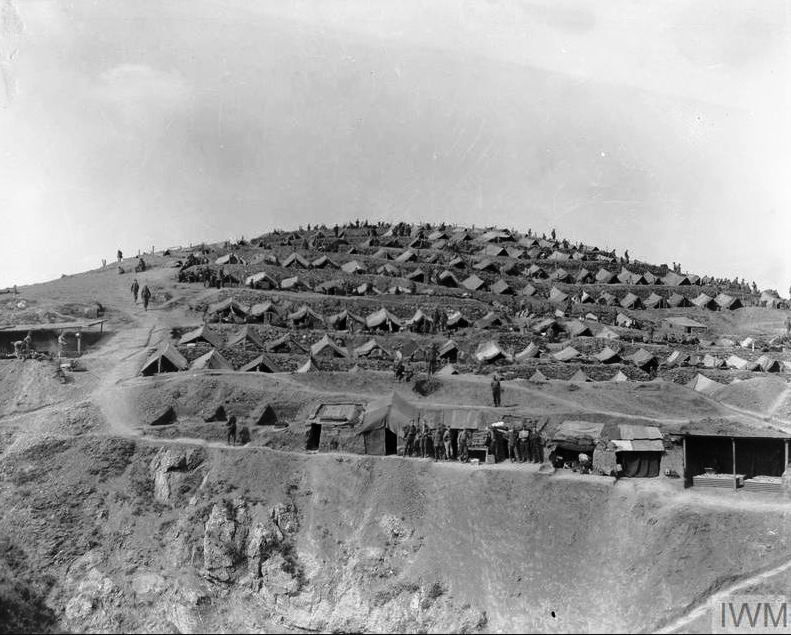

On 12 November the battalion marched 12 miles from Revelles to Longore station and entrained for a three-day journey to the south of France. A week later, on 19 November, they left the killing fields of France and boarded the SS Marathon at Marseilles. They set sail via the Mediterranean and the Aegean Sea for the Port of Salonika (now modern-day Thessalonica) in the northern Greek region of Macedonia. After disembarking at 4pm on 26 November in Salonika, they marched to a camping ground a couple of miles outside the city.

William wasted no time in describing the conditions in his diary:

“Saturday Nov 27th Reveille at 7A.M. On looking out of our tents we were all surprised to see about a foot of snow on the ground, and I for one thanked my God that we had pitched our tents the night previous. There were about twenty of us in a tent so we had not felt the cold very much during the night. We had rather a rough toilet that morning having to go about a quarter of a mile for a wash, & then when we got to the stream we had to break the ice before we could wash, also we had to shave in icy water it was champion I can tell you. At 9A.M. we had to turn out to peel the Coy’s potatoes, my word what a job, peel a potato then blow the hands for about five minutes.”

William and his unit had arrived in Macedonia just as the Allies were withdrawing back from Serbia into Greece and a front line was being established about 20 miles north of Salonika. The Macedonian Front was destined to become a sideshow to the war in France and Flanders and the BSF soon became the forgotten Army. On a 260-mile front that stretched from Albania in the west to the mouth of the River Struma, just east of Salonika, hostilities turned into a stalemate that were to last for three long years.

The British Forces held 90 miles of front including the Struma Valley and the strategic position of Doiran on the Macedonian border. On the Struma Plain there wasn’t a continuous trench line but a series of redoubts or entrenched strongholds. In between these were lines of barbed wire entanglements which were patrolled periodically.

Living conditions for soldiers on both sides were harsh with extreme weather conditions. During winter they had to endure blizzards, trench foot and frostbite and in summer temperatures of 112 degrees in the shade. In a barren and hostile terrain, the only reliable mode of transport for supplies being the pack mule. To the troops the campaign was characterised by the ‘3 M’s’- (Mules, Mountains and Mosquitoes).

Salonika Tent Encampment

Early in the campaign it was feared that the Port of Salonika would come under attack, so it was made into a bastion with a trench line about eight miles north of the city protected by hundreds of miles of barbed wire. The troops nicknamed Salonika the “Bird Cage” owing to the huge amounts of barbed wire used. William and his unit were to do their share of the work. Trudging over the surrounding hills from one location to another they made roads, dug trenches, laid wire and fortified outposts for weeks on end.

The troops of the BSF were to lead a nomadic lifestyle for the next three years, marching along the front line from one position to another, patrolling or manning trenches and outposts where they sweated under mosquito nets to keep the fleas and mosquitoes at bay. Behind the front line they laboured digging trenches or making and maintaining roads. They lived in tented camps and conditions were at best primitive, washing their laundry in streams and bathing in rivers. This wasn’t without its risks as William was to later note in his diary;

‘I went down to the river Struma for a wash and whilst there the Bulgars sent a volley of shells over wounding about six of our fellows but God preserved me'.

The 80th Brigade was using Tasli on the coast as a Depot as it had a pier from which to unload supplies from Stavros across the Gulf of Orfano. It was also used as a rest camp, where the soldiers would replenish kit, get their medical needs sorted and relax and play sports before preparing for their next spell on the front line. William spent his spare time writing letters, attending church, playing football and going for long walks along the coast. Shows were put on for entertainment and necessities were bought at the EFC, the Expeditionary Force Canteen whenever the chance arose.

William must have been very good at football, from just playing for his Platoon, then his Company, he soon got picked to represent his battalion. When away from the front line at the rest camps they played against other regiments, the crews of Royal Navy ships and even in Internationals when English soldiers would play against the Welsh or Scottish contingents. In his diary he records every football match he played in, who the opponents were and the score. Eventually he was to become Captain of the Regimental football team.

R & R

R & R

William attended church as often as possible and on one occasion declined to play for the battalion football team in favour of attending a church service. His devotion to his faith is demonstrated in his diary with prayers and psalms quoted regularly throughout its pages, with every Saint’s Day also noted. At every opportunity he would read his bible or as he called it ‘The Book’.

As well as remembering his mothers and siblings’ birthdays and anniversaries in his diary he notes every cigarette and rum issue. Although a non-smoker, William still accepted his ‘fag’ ration and gave them away to his friends.

As well as faithfully recording the day’s events in his diary William was also a prolific letter writer, eagerly awaiting letters, parcels, local newspapers and magazines from home. He wrote regularly to his mother, his sweetheart Annie, his brothers and sisters and niece Nellie Crouchley. He also wrote letters home on behalf of some of his fellow soldiers who couldn’t read or write very well.

He kept in contact with Rev. Scott, the Vicar of St. John’s and communicated regularly with Rev. Twemlow who had moved from St. John’s in 1911 and was now incumbent at St. Peters church in Preston.

He also corresponded regularly with members of St. John’s church, especially his brother-in-law Samuel Marsden who had married his sister Betsy. Sam, an accountant at Bickershaw Colliery was a prominent member of St. John’s. He was a Churchwarden, Honorary Secretary of the Curate Fund, Superintendent of the Good Shepherd Mission Room in Bamfurlong and Secretary of the Sunday School Bank.

William also kept in touch with William Forrest, the choirmaster who lived in Ashton in Makerfield, Mr. Gaskell the organist, Ernest Dawson, a grocer who lived at 360 Warrington Road and a fellow member of the choir. He also corresponded with Miss Davies the Primary School Headmistress and young Jack Wigan from 293 Warrington Road, a Sunday School pupil of his.

He didn’t forget his friends and neighbours back home in Warrington Road and wrote to Jim Southworth of No. 64, Bob Dodd who worked at Moss Hall Colliery and lived at No. 141, Jim Higson of No. 232, George Henry Gaskell who lived at No. 364, Matt Round of No. 359 and Jim Blakeley of No. 402. He also wrote to his friend Peter Gorton of Lily Lane in Bamfurlong and kept in contact with John Salter, his foreman at the Sewerage Works in Bickershaw Lane.

An entry in his diary on 2 March 1916 reads:

“In the evening I wrote a letter to one of my old pals Sgt. J. E. Grimshaw V.C. of the Lancashire Fusiliers.”

John Elisha Grimshaw was of course a hero back home in Abram. His Victoria Cross was one of the famous ‘Six VCs before breakfast’ won in Gallipoli by 1 Bn Lancashire Fusiliers on 25 April 1915. Before moving to Platt Bridge, John had lived at 24 Warrington Road, Abram.

William must have been an intelligent and capable man who his superiors saw potential in. He refused promotion to L/Cpl and twice he refused jobs as a ‘Batman’ or servant to his Platoon Officer. He also declined a chance to join the Reconnaissance Scouts, the eyes and ears of his battalion. His reason every time was that he didn’t want to leave his friends in his platoon. He was eventually nominated to go on a week long Range Finding course and came top with the highest score.

In 1916 an epidemic of malaria broke out in the region. Most cases occurred in units serving in the Struma Valley, a British area of responsibility, at the time one of the worst malarial areas in Europe.

Rates of infection were such a problem that both the British and their Bulgarian opponents withdrew to the hills during summer months and just patrolled the valley. By the end of the campaign the BSF alone had suffered 156,309 cases of malaria, resulting in 819 deaths. For every battle casualty there were three others from malaria, enteric fever, cholera, typhus, influenza, measles and other diseases.

Despite daily doses of quinine William was not to escape the dreaded mosquito. On 6 March 1916 he recorded his first attack of fever, with a temperature of 101 degrees he was put on light duties. For the rest of his time in the army he suffered recurring attacks of malaria along with other illnesses and was hospitalised several times.

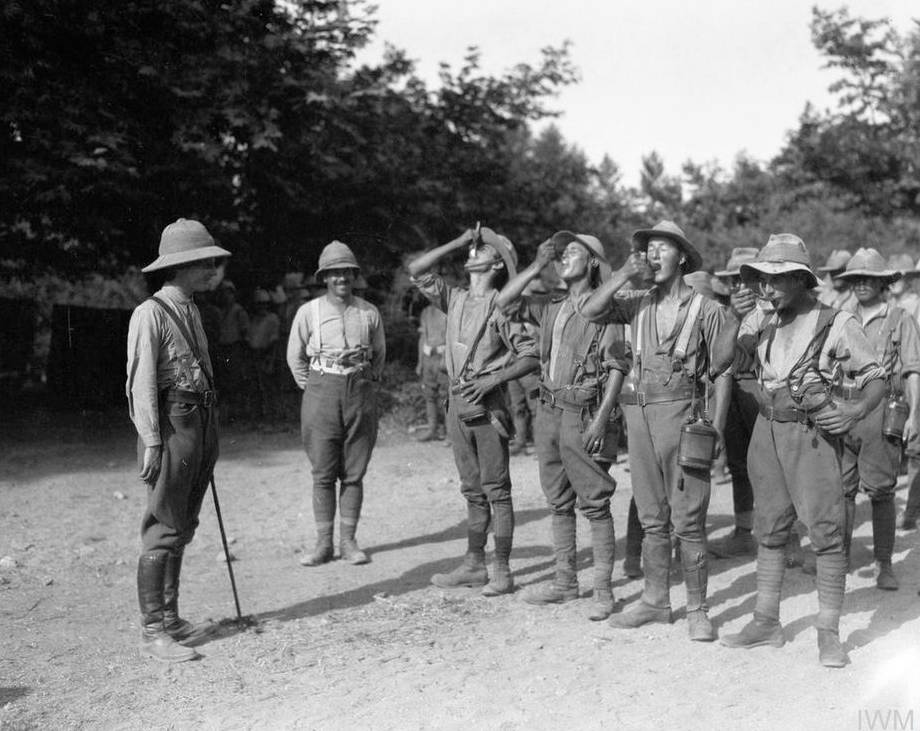

Salonika - Daily dose of quinine!

At 7.15 am on 3 April 4th Bn KRRC struck camp in the hills and marched off to relieve the Naval Brigade in the front line on the Gulf of Orfano. They were positioned on the extreme right flank of the Allied front line, that stretched 260 miles westwards to the Adriatic coast. William’s Company pitched their bivouacs on the beach 100 yards from the sea. Here the battalion dug new trenches, erected more barbed wire and patrolled the front line. They bathed and washed their laundry in the sea then went for a swim leaving them to dry on the sands.

This was one of the better spots to fight the war from as William describes:

“Friday June 23rd 1916: Went to work on dugouts in the morning. In the evening went for some water up the hills which was beautiful, as clear as crystal. By the fountain there was a large well cut in the rocks here under the shelter of the olive trees our fellows would take a dip when too tired to walk down to the sea. From this point there is a splendid view, a narrow path zig-zagging down the hill-side among the trees and shrubs, then the plain with the sheep, goats & oxen grazing peacefully with their different toned bells around their necks stretching unto the sea, and there one sees the sea so peaceful as a rule with three or four battle ships at anchor and a few small boats belonging to the native fishermen. I have sat at this point for hours drinking as it were the beauty of this scene.”

Salonika - Trench Digging

Salonika - Trench Digging

At the end of June William’s ‘D’ Company marched six miles and set up camp in wooded country, it was such a pretty spot they nicknamed it ‘Watermelon Camp’. Here for the next three weeks, they laboured, making improvements to the roads. They also went on two- and three-day military manoeuvres in the mountains up to an altitude of 2,000 ft where they bivouacked overnight in freezing conditions.

On 24 July after three and a half months on the coast the 4th Battalion loaded up their mules and marched for two days up to a new location in the hills at Kato Krusoves, overlooking the Struma Plain.

They immediately started digging trenches with pick and spade in the solid rock but found it very hard work. As a miner William was used to it but he felt sorry for some of the chaps who weren’t used to the pick as they kept jarring their wrists up. Eventually it was conceded that the rock was too hard for the picks, so holes were made with hand drills and the rock was blown out with explosives.

This work making a defensive line went on for week after week, after the trenches were dug, they had to be protected with barbed wire. At the same time the never-ending routine of manning dugouts, picquet duty forward of the wire, wire patrol and reconnaissance patrolling against the enemy went on. On 3 November William’s Company were sent back from the front line to a camp at Kucos for a week to rest.

Convalescence in Malta

Over a period starting in September through to November William had suffered persistent bouts of fever and being unable to fulfill his duties properly he was placed on light duties several times. On 25 Nov, the anniversary of their landing at Salonika he wrote in his diary:

“Came off picket at 6.30AM, I fried some bacon for my breakfast but it made me bad. I paraded with my Platoon at 2PM for work on the trenches, feeling about half dead, I came back with a very bad head, and scarcely able to take my breath”.

Two days later he reported sick and was immediately strapped to a mule and transported to an advanced dressing station at Tasli. After a checkup by a doctor, he was taken by boat across the Gulf of Orfano to the 83rd Field Ambulance RAMC hospital at Stavros where he was admitted to a malaria ward.

By 9th December his condition had worsened, and he was in a delirious state. Ten days later William was transferred to the hospital ship Panama which then made its way round to Salonika to pick up more patients before sailing for Malta on 22 Dec.

The Panama arrived in St. Paul’s Bay in Malta on Christmas Day 1916. The next day it sailed round the island and docked at Valletta where William was admitted to the Floriana Military Hospital overlooking the Grand Harbour. Formerly the Floriana Barracks, it was converted to a 1,304-bed hospital in readiness for the influx of malarial patients from Salonika.

William was to spend ten weeks in Malta recovering. As he got stronger, he was put on light duties in the Red Cross kitchen then eventually transferred to St. Peter’s Convalescent Camp at Ghajn Tuffieha on the other side of the island.

He spent his time looking round town, watching football matches, attending concerts and lantern slides and writing scores of letters in the YMCA tent. Most importantly for him he attended church as often as possible to receive Holy Communion. Whilst there he bumped into Bill Battersby from Wigan who he had joined up with two years previously.

Eventually William was marked fit for active service and on 4 March 1917 he embarked on HMS Cameronian bound for Salonika and a return to his unit. However, it wasn’t long before he had a relapse, a week later he collapsed whilst on sentry duty and over the next few weeks had recurring bouts of fever with temperatures of 104 degrees.

On 28 March 1917 William was transferred to the 3rd Entrenching Bn. This was a temporary unit raised to assist the Royal Engineers in building defences in the rear areas. For the next three weeks they were to spend all their time in the hills making roads under RE supervision.

On 20 April he collapsed again with a temp of 104.6F and vomiting continuously was taken to see the medics at 83 FA RAMC. Two days later he was transferred to hospital at 27 CCS with a racking cough and ulcerated throat. On three doses of quinine a day he started to feel better and was sent to No. 6 Rest Camp. Despite a bout of dysentery, he managed to represent the camp at cricket against the medical staff.

Salonika - Ambulances

He was marked fit for service on 4 May but on hearing that the 3rd Entrenching Bn had been disbanded decided to join a draft of men bound for 3 Bn KRRC back in his old Brigade. After a spell in the front-line trenches with 3 Bn where they had skirmishes with the Bulgarians, William finally got orders to rejoin to his old unit. On 18 June he returned to the 4th Battalion at Kastri, after an absence of six months.

Here at Kastri, one of the permanent camps, military training went on as normal with kit inspections, PT, route marches, rifle drill, weapon training and shooting competitions. They would also be required to take their turn doing guard duty and fatigue details such as working in the cookhouse or collecting and cutting wood for the cook’s fires.

Despite the war the Divisional Commanders were determined to keep the morale of the troops up with football competitions at all levels. On 5 Sept William was in a party of 14 footballers that left Tasli on a three-day march to Div HQ to represent the 4th Bn KRRC in the Divisional Platoon Football Final. Despite not feeling well William played in the game which they lost 1-0 to the Lovat Scouts. William notes that they were not disgraced as their Scottish opponents had an international and four professional players in their team.

On their way back to their unit William felt so bad that he reported sick at Nigrita. He was taken by ambulance to 82 Field Ambulance where he was diagnosed with scabies and admitted to an isolation ward where he underwent a sulphur vapour treatment.

Ten days later he was discharged and on return to his regiment was put on light duties. On 6 Oct he reported sick again and was sent to 81 Field Ambulance where once more he was diagnosed with scabies and had to undergo the sulphur vapour treatment again. He notes that this time the fumes were so strong they made him vomit. Whilst being treated for scabies he had another attack of fever and was put on a liquid diet.

After a week in hospital William returned to his unit and normal duties but it wasn’t to last for very long. On 20 October he reported sick with 14 boils on his body and was excused duties, a week later his body broke out in a rash. He was sent to the Field Hospital once again where the doctors couldn’t decide if it was scabies again or scarlet fever.

On 1 November he was put on a light railway that was used to transport equipment and taken round the Gulf of Orfano to the Field Hospital at Stavros. William was to spend two months at Stavros. On Christmas Eve 1917 he was discharged and boarded the SS Princess Ena which sailed for Salonika. It was to be his second consecutive Christmas on the high seas.

William describes his return to Salonika:

“Tuesday Dec. 25th 1917 Christmas Day. We got in Salonica about 9A.M. and marched up to Karassi Rest Camp which had been turned into the temporary Base owing to measles having broken out at the Base at Summer Hill Camp. We got in camp just at dinner time.

Our Christmas dinner consisted of a tin of bully beef and biscuits the worst I have had yet. At tea time we fared even worse for we only got a biscuit. I went to evening service at 6.30P.M. in the church tent which comforted me somewhat, but when the pangs of hunger are gnawing at you it is hard to collect ones thoughts together for prayer and meditation. There was a rum issue about 9P.M.”.

The Last Year of the War

At the beginning of 1918 the Greek Army had been reorganised and joined the Allied Force which was preparing for a major offensive intended to end the war in the Balkans.

In bitterly cold weather on 6 January William rejoined his unit who were on the front line at Apadji. He was assigned to No.1 Redoubt and the next six days were spent strengthening defences, patrolling the wire and on OP duty. On 10 January he notes that they had to rub their feet with whale oil to prevent frostbite.

Two days later they were relieved by the 3rd Battalion and moved into billets at Marian Camp. When not on military training the troops were utilised on improving the River Struma defence line. On 27 Jan they moved to Agomah and saw a period of action patrolling in front of the wire, at one time coming into contact with Bulgarian Forces and suffering three casualties. In the village of Ada, they set ambushes in the hope of surprising enemy troops and William notes that they saw an enemy plane brought down, the occupants being burnt to death.

During February William was taken ill several times, on the 27th he was strapped to a mule once again and taken to 82 Field Ambulance at Dimitric. In early March he was discharged and rejoined his battalion who had moved to Nigrita. William had another malaria attack on 17 March and was admitted to 86 Field Ambulance. Three days later whilst still at the Aid Post he wrote:

“Wednesday March 20th 1918 The third anniversary of my enlistment having served almost three years on active service without a day’s leave home, when I shall get a few days at home I don’t know there doesn’t seem to be any chance at all. may God give me patience and strength to endure. I feel a bit stronger today and expect going back to my Batt any day. My chum Joe Ward came into hospital today with fever’’.

On 2 May William collapsed again with fever and was taken to 82 Field Ambulance, the next day he was admitted to hospital at 40 CCS where he stayed for eight days.

The next month William’s Battalion were recalled back to France, on the 17th of June they bade farewell to the 27th Division and departed Guvesne by train and travelled across Greece to the port of Itea. On the journey he records that the steam engine failed to climb a gradient and came to a standstill. After reversing down again and after two more failed attempts the occupants were ordered out and made to push the train up the hill.

A week later the Division embarked aboard SS Odessa bound for Otranto in southern Italy. Whilst at sea William had another bad malarial attack and on arrival in Italy was admitted to 79 General Hospital. The next day he was diagnosed with an enlarged spleen and was in a hospital bed when the train carrying his unit left without him on their way to France.

Three weeks later, on 16 July he was released from hospital and left Otranto by train with other discharged patients. Over the next 10 days they travelled over 1,800 miles to the north of France, finally reaching Le Havre on Friday 26 July. On arrival back at his unit, William immediately reported to the orderly Room and applied for home leave.

A Spell of Leave in Blighty

Armed with two day’s rations and 16 days' supply of quinine William sailed from Boulogne for Folkestone on Tues 13 Aug. He arrived at Wigan North Western station at 6.30 am the next morning. After a tram car ride to Platt Bridge and a walk up Warrington Rd he was finally back home after three years away on active service.

The next twelve days were spent catching up with family and friends in Abram and along with Annie made visits to relatives in Lowton, Downall Green and Ashton in Makerfield, and called in on his employers at the Council offices and at the sewerage works.

He spent as much time as possible with Annie, walking through the fields to Bickershaw, or gathering blackberries in the fields of Ingram’s Farm. William was very knowledgeable about herbal medicine and would take the opportunity on walks to look for comfrey and other plants that could be used for medicinal purposes.

In a bid to return to normality he took his mother to church and to Wigan Market to do shopping, joined in with choir practice and took Sunday School classes at the Good Shepherd Mission in Bamfurlong.

On the Saturday of the first week, he went to Wigan to buy Annie an engagement ring, later they had supper with good friends Matt and Helen Round. The next day after church they walked down to Ingram’s farm for supper. During the second week he took Annie and her sister Molly to the pictures and spent a day in Preston visiting Reverend Twemlow at St. Peter’s church.

On the Friday William took Annie to Wigan Market. After a meal in town, he had his photograph taken then accompanied her to Prospect Mill in Platt Lane, Hindley to pick up her wages.

On Monday 26 August he travelled down back to London with his friend Dan Burgess who was also reporting back to his regiment from home leave. Dan lived at 482 Warrington Road with his widowed mother and brothers Luke and Richard.

The Western Front

4th Bn KRRC had arrived back in France from Salonika in time to take part in the ‘Hundred Days Offensive’. A series of offensives starting on 8 August 1918, designed to push the Germans back from their gains of their own Spring Offensive back in March.

On 3 September, after his home leave William reported back to his unit at Martin-Eglise on the outskirts of Dieppe. The Battalion had been assigned to the 151st Infantry Brigade of the 50th Division alongside the 6th Bn Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers and 1st Bn King's Own Yorkshire Light Infantry.

Ten days later his battalion moved by train from Dieppe on the coast to Bouquemaison where they started training for battle in earnest. From there they moved to Bertangles on the Somme, then on 1 October they moved into the support line at Epehy, north of Saint Quentin, finally relieving an Australian regiment in the front line at Bony. Here they were warned for an upcoming attack on the once impregnable Hindenburg Line.

Just before dawn on 3 October the attack was launched and 4 Bn KRRC went over the top, despite suffering some casualties from their own artillery barrage all objectives were taken. The next morning, they were relieved briefly but went into action again at dusk. Again, all objectives were taken with very light casualties suffered. The Bn War Diary states that they took two officers and 52 men prisoner and captured 25 machine guns and two trench mortars.

William had been chosen to become a Brigade runner and was attached to Bde HQ, he spent the battle carrying dispatches between headquarters and the various units in the Brigade. This was a very hazardous job, and many runners were killed or wounded.

The German Army was in withdrawal all along the front line and the Allies kept the pressure on with a series of attacks. On 10 October Williams battalion moved out of the line for a spell of rest in the village of Maretz.

They left Maretz on the 16th and moved to Escaufort, from where, the next morning they went into action again at dawn. During the battle William and another runner had to take a dispatch to Bde HQ, part of an entry in his diary describes his experience:

“On our way back I helped many of my Batt chaps that were wounded to the sunken road to be picked up by the motor ambulance. Never shall I forget the hellish sights I saw on that sunken road; many of my intimate friends that had been with me from the beginning of my army life lay there dead or dying, as I looked back on that road it seemed a broad red stream with the blood of my comrades. I could have stopped helping chaps all day but duty had to come first I had my message to deliver at Hd Qrts. Our chaps gained their objective, but at a cost”.

On the morning of the 18th, they went over the top yet again and captured their next objective. The next day 50th Div was relieved and 4 KRRC moved out of the front line to the village of Busigny.

On 28 October whilst taking dispatches to the Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers William took ill with another malarial attack and on return had to report to the MO for some quinine. The next day his unit left Busigny via Maurois for rest billets in Le-Cateau, William managed the first part of the route march but was too weak to complete it so had to be transported on one of the limbers.

The Battalion War Diary shows that the casualty returns for the month of October 1918 were 74 killed in action, 272 wounded and five missing.

On 3 November, William moved with Advance Brigade Headquarters to Bousies, in preparation for an attack the next morning on the Mormel Forest. Two days later he wrote in his diary:

”Tuesday Nov: 5th 1918. We rigged a bivouac up for about eight of us, by the side of an 8” inch gun that my Battalion (4th KRR) had captured. Pte Fox and I had to go to the Inniskillings with despatches and two coils of telephone wire. It was a treacherous road we had to travel being swept by machine gun fire pretty frequently. On our way back we came across scores of our dear lads wounded, and we gave a helping hand to the R.A.M.C. with the stretchers. As we were going along with one poor chap badly wounded on the stretcher a machine gun opened out on to us the poor fellow was hit again, and I was very fortunate but God preserved me once more, for as I was going along with the stretcher on one shoulder and my rifle on the other by my side a bullet came and caught the butt of my rifle as it hung by my side, and it turned away into the hedge”.

Over the next couple of days William records in his diary accounts of close calls from artillery shells and machine gun fire whilst moving about the battlefield carrying his dispatches.

On 7 November he wrote: “My Batt who occupied St Aubin suffered very heavy losses here our Commanding Officer Capt Tryant getting killed. I lost a lot of my pals here that had been out with me ever since we first joined the 4th K.R.R.s in France in 1915 and this is the last in the trenches I believe for my Batt”.

The next day his Brigade went over the top again and gained their objective, later that day they were relieved and moved out of the Front Line to Montceau-les-Leups.

At 9am on the morning of Mon 11 November 1918 William had the task of taking dispatches round the Brigade and informing the various Unit Commanders that the Armistice had been signed and hostilities would cease at 11 o’clock, the Great War was about to end after 1,459 days of bloodshed.

In the three years and four months that William had served on active service with 4th Bn KRRC his unit had suffered 149 killed, 474 wounded and 26 missing. By the end of hostilities, the total casualties for his unit during the whole of the Great War amounted to 334 killed, 1,125 wounded and 307 missing in action.

Demobilisation started in December 1918, but it wasn’t until 22 February 1919, the day after his unit moved from La-Longueville to Jolimetz in the Forest of Mormal that William was finally told that he was being sent home. He was moved to a delousing camp where he had a hot bath, issued new underclothing, had his khaki uniform fumigated and underwent a medical examination.

Four days later he embarked aboard the SS Casarea at Dieppe bound for Southampton, then travelled to a Dispersal Unit at Prees Heath Camp in Shropshire to be formally demobilised.

William’s final entries in his diary were made on Friday 28 Feb 1919.

“I arrived at Wigan station about 3AM and stayed in Soldiers Rest Billet until 4 AM. When I proceeded to Platt Bridge by the first workmen's car. As I journeyed along Warrington Rd Abram on my way home I called on my sweetheart and saw her just before she set out to work. After a short stay I made my way home getting here about 8AM. After a few minutes with my Dearest Mother I had a little breakfast and went to bed for I was completely fagged out not having any proper sleep for three or four nights.

This ends my career as a soldier of his Majesties Forces. I leave the Forces as I started it four years ago as a common, private, rifleman but by the grace of God, one who always strived to do my duty, not counting the cost. I am one of millions who will pass out of this great army of ours into the obscurity of civilian life, unknown, and forgotten by the world (unless another war should crop up); but by the grace of god I hope to carry on the fight for Christendom until the bugle sounds the The Final Last Post.

In a later postscript to his diary he wrote: I have since received my 1914-15 Star, General Service Medal, Victory Medal, also the Army Football medal I won there.”

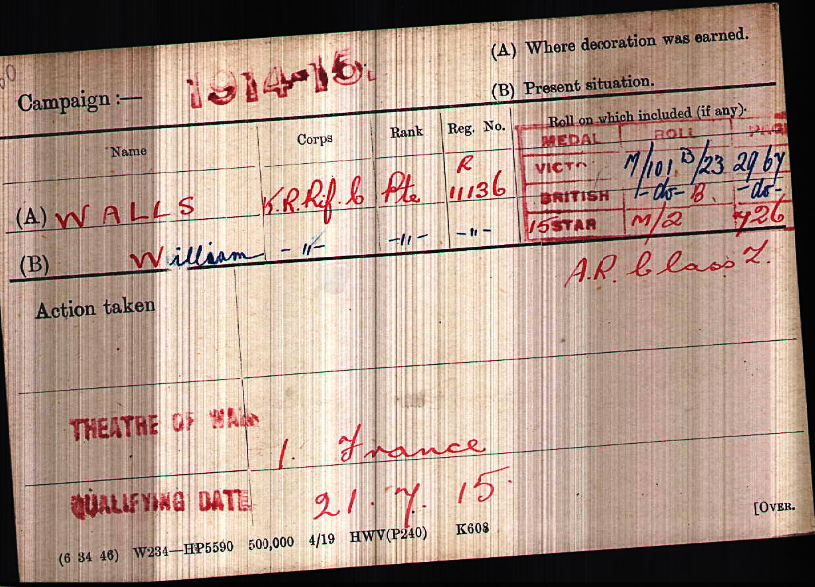

William's Medal Index Card

Epilogue

After the war William returned to his old job at Abram Sewerage works. He married Annie at St. John’s church on 20 September 1919, their witnesses being his brother James and her sister Mary. They went on to raise two sons, James born in 1920 and Arthur in 1924.

The register of England & Wales taken on 29 September 1939 at the start of the Second world war shows William, Annie and their two sons living at 316 Warrington Road. His occupation is shown as ‘general labourer sewer man’ and a ‘part time ARP warden’.

William Walls died on 17 May 1973 aged 81 at 394 Warrington Road, Abram, the day after burying his beloved wife Annie’s ashes in St John's churchyard. His cremated remains were buried alongside her 12 days later on 29 May in Grave No. 795 B CE.

Graham Taylor - Aug 2020

Abbreviations

4th Bn KRRC 4th Battalion Kings Royal Rifle Corps

ARP Air Raid Precautions

Bn Battalion

Bde Brigade

Bde HQ Brigade Headquarters

BSF British Salonika Force

Capt Captain

CCS Casualty Clearing Station

CE Church of England

Coy Company

Div Division

EFC Expeditionary Force Canteen

FA Field Ambulance

HE High Explosive

Inf Div Infantry Division

KRR Kings Royal Rifles

KRRC Kings Royal Rifle Corps

L/Cpl Lance Corporal

MO Medical Officer

OP Observation Post

Pl Platoon

Pte Private

PT Physical Training

RAMC Royal Army Medical Corps

RE Royal Engineers

Sgt Sergeant

SS Sailing ship

YMCA Young Men’s Christian Association

VC Victoria Cross

WW1 World War One

Acknowledgement

Thanks to Susan Berry for transcribing the diaries of William Walls

Photographs

Photos depicting Salonika are copyright of Imperial War Museum

Main Sources

Ancestry Births, Marriages & Deaths 1837-2007

Ancestry Census records 1841-1911

Lancashire Online Parish Clerks

National Archives

The Long Long Trail

The transcribed War Diary of Rifleman William Walls of Abram

War Diaries 4 Bn Kings Royal Rifle Corps

Wigan & Leigh Archives

Wikipedia