Wigan Workhouse and the Poor Law Union

Introduction

Many people in local and family history circles are still intrigued by Wigan Workhouse but apart from Wigan & Leigh Archives there does not seem to be a ready reference. This article explains the history of Poor Law, the formation of the Wigan Poor Law Union, the building of the new Workhouse in Frog Lane, the conditions inside and the regime followed by its inmates.

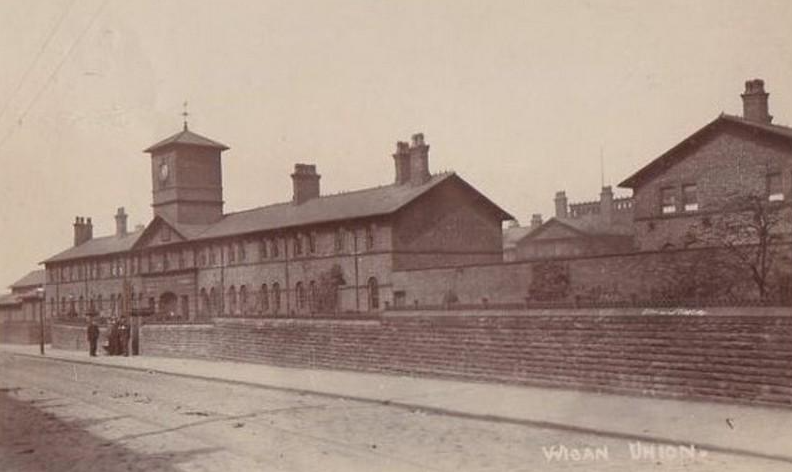

Wigan Workhouse early 1900's

Wigan Workhouse early 1900's

To most people the mere mention of the word ‘workhouse’ invokes grim images of Oliver Twist and the poverty in the slums of Dickensian London in the Victorian era. The poor and destitute had no option but to enter these notorious institutions, which had a reputation for the terrible conditions and harsh treatment of their inmates.

The origins of the workhouse can be traced way back to the 14th century. Edward III passed the earliest medieval Poor Law, in the aftermath of the Bubonic Plague (more commonly known as the Black Death) which killed approximately 40% of the population between 1348 and 1350.

The decline in population resulted in a shortage of workers and created a simple case of supply and demand, this meant wages for labourers rose which in turn forced up prices. The Act required that anyone who could work did so, wages were kept at pre- plague level and food was not overpriced. In 1388 the Statute of Cambridge Act was passed which placed restrictions on the movement of beggars and in particular migrant workers, in a bid to stop them migrating around the country in search of higher wages.

Historically the church had been responsible for providing relief for the poor and needy. However, following the Reformation and the dissolution of the monasteries by Henry VIII between 1536 and 1541, this vital source of relief to the poor was drastically reduced.

In the Elizabethan era, vagrancy was increasing sharply, due to a growing population, rising poverty and inflation. In 1572 the Government, fearing that social order might be threatened which could lead to rebellion, passed new legislation, known as the Vagabonds Act.

The Act formally transferred responsibility for poor citizens from the church to local communities by introducing a property tax to raise funds for their welfare. A Justice of the Peace would register those who were poor and sick and assess the rate of tax. In each parish two Overseers of the Poor were appointed to collect monies and to distribute relief to the destitute. Everyone had to contribute and those who refused could be sent to jail. To qualify for assistance the poor had to live locally and were grouped into three categories:

The Impotent Poor - those who were unable to work due to old age, disability, or infirmity. Limited relief was provided to this group by the community in which they lived.

The Able Bodied Poor - these were classified as being physically able to work, and to prevent them from becoming a burden on their community or from becoming vagrants, they were forced into employment.

Lastly Vagabonds - these were the homeless and had no means of income. They drifted from place to place and survived by begging or stealing. It was thought they were lazy, idle, and threatened the established social order.

The 1572 Vagabonds Act took severe action against rogues or vagrants who could be stripped to the waist, whipped, and bored (the practice of burning a hole through the cartilage of their right ear with a hot iron). Or even sentenced to death and hung if persistently caught begging.

Over the centuries numerous pieces of legislation and amendments concerning poor laws were passed. The two key pieces of legislation that eventually paved the way for the modern welfare state were the Poor Law Acts of 1601 and 1834.

Poor Law Cartoon

Poor Law Cartoon

The Act for the Relief of the Poor, also known as the ‘Old Poor Law,’ was passed in 1601 at the end of the reign of Queen Elizabeth 1. It remained the basis on which the poor were helped for the next two centuries. It consolidated all previous legislation and enabled a compulsory poor rate to be levied on the wealthier members of the parish. This ‘Poor Rate’ became the forerunner of the old domestic rates and the current council tax.

There were two types of relief, ‘Outdoor Relief’ was for poor people living in their own homes who would be given money or relief in kind, such as food, clothes, shoes, goods, and coal. Anyone who received parish relief was marked down as a pauper.

‘Indoor Relief’ saw the poor admitted to local Alms-houses, the ill admitted to hospitals and the orphans into orphanages. The ‘Idle Poor’ would be taken into the Poorhouse and made to work for their keep.

Begging was banned and anyone caught was whipped and returned to their place of birth. Alms-houses (the precursor to the workhouse) were established, these generally were groups of six to twelve houses built and run by benefactors to house the genuinely needy, such as the elderly and infirm, disabled and widows.

In 1723, legislation, known as the ‘Knatchbull Act’ was passed by the government. It introduced the ‘Workhouse Test,’ which stipulated that any person who wanted to receive poor relief had to enter a workhouse and undertake a set amount of work in return for their keep. The test was intended to prevent unnecessary claims on a parish's poor rate. As a direct result of the Act, hundreds of parish workhouses were built in England and Wales. Wigan is first recorded as having a workhouse in 1732 when George II was on the throne and by 1777, a Parliamentary report showed that Wigan Workhouse had a capacity for two hundred inmates.

New Poor Law

The Poor Law Amendment Act of 1834, also known as the New Poor Law, was aimed at reducing the cost of poor relief which was spiralling out of control. Under the new law, all relief to the able-bodied in their own homes was forbidden, and all who wished to receive aid had to live in workhouses. In some areas though, mainly in the industrial north of England, there was much opposition to the Act and outdoor relief continued for a period.

The authorities decided that the most effective way to eradicate pauperism at minimum cost was to make conditions in the workhouse deliberately worse than those of the 'independent labourer of the lowest class,’ in order to discourage the poor from relying on parish relief.

The changes to the Old Poor Law system were implemented by three Poor Law Commissioners based at Somerset House in London. The commission lasted until 1847 when, after a scandal at Andover Workhouse in Hampshire it was replaced by a new authority, the Poor Law Board. Poor Law Unions were then created by the grouping together of parishes, under the responsibility of a Board of Guardians. The Guardians were then responsible for the administration of poor relief over all the individual parishes. The New Poor Law encouraged the large-scale development of workhouses by Poor Law Unions during the Victorian era.

Wigan Poor Law Union

Wigan Poor Law Union came into being on 2 Feb 1837 (two months before Queen Victoria came to the throne). It had the responsibility over an area of seventy square miles, with a population of 58,000 inhabitants living in twenty parishes. There were three workhouses in operation at the time, at Wigan, Pemberton, and Hindley.

It was overseen by a board of twenty-eight guardians, the size of the parish boundary determining the number of guardians. Wigan Parish had five guardians, Ashton in Makerfield, Hindley, Orrell and Pemberton had two each. The fifteen other parishes of Abram, Aspull, Billinge Chapel End, Billinge Higher End, Blackrod, Dalton, Haigh, Ince, Parbold, Shevington, Standish with Langtree, Upholland, Winstanley, Worthington and Wrightington had one guardian each. A Workhouse Committee was elected which reported directly to the Board of Guardians

Poor Law Inspectors reported that the existing Wigan Workhouse at 75 Frog Lane was too small, overcrowded, and unsuitable under the new system. In 1855 the Union decided that a new larger purpose built workhouse would have to be built. Pemberton workhouse which only had a capacity to house 60 had been closed and it’s inmates moved to the Frog Lane site.

Applications for a loan, firstly to the Government, then the Poor Law Board were unsuccessful. Eventually a loan of £13,800 was secured from the Pelican Life Assurance Company of London, it would be paid back by instalments at 5% per annum.

Accordingly, land adjacent to the existing workhouse was purchased from A. F. Haliburton Esq, the deeds being signed by the Board of Guardians on 18 August 1855. Plans were drawn up by Manchester architects, Henry Travis, and William Mangnall for the new workhouse to be built on the 15 acre site, which would be bounded by Frog Lane, Lower St. Stephen Street, Gidlow Lane and Barley Brook to the rear of houses in Diggle Street.

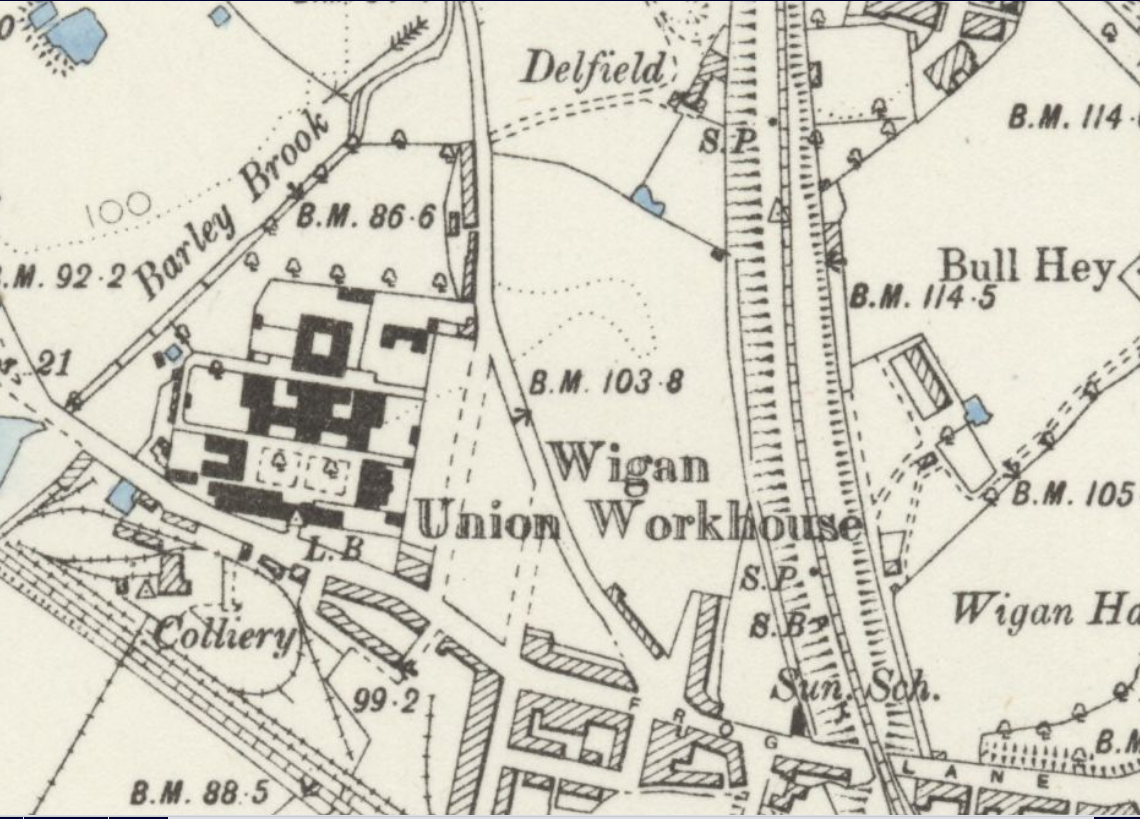

1898 - Map

1898 - Map

Plan of Wigan Union Workhouse Frog Lane

Plan of Wigan Union Workhouse Frog Lane

The foundation stone for the new Wigan Union Workhouse was laid on 2 April 1856 by Chairman of the Guardians, Joseph Ingram JP. The existing workhouse had to keep on running as usual during the construction and transition phase. Hindley Workhouse closed and the remaining 67 paupers were transferred to Wigan Workhouse in December 1857. The lease was sold to a Mr. Gaskell for £50, who started work on converting the property to cottages. The Board of Guardians held their first meeting in their new board room at Frog Lane on Friday 5 March 1858, construction was finally completed a few months later .

Main Building

Main Building

The minutes from the Board of Guardians meeting held on 18 June 1858 show that the previous week the new workhouse had discharged thirteen inmates but had admitted a further fifteen and the total inmates at present was 395. The cost of spending on the inmates per head was 2s.10d. Outdoor relief had been provided to 2,873 men, women, and children. It was noted that Mr. Fairclough had put a tender in of £12.10d for the making and fixing of an inscription stone over the doorway.

Lawrence Marsden, the Master of the workhouse died in early 1861 after only three years in the role. The census of that year shows his wife Mary in temporary charge, until a new Master could be appointed. Her daughter Mary took over as assistant Matron, the staff consisted of a school master, school mistress, sick nurse, imbecile nurse, and a porter.

Local couple John and Alice Lowe were appointed their successors on 7 June 1861. Aged 26 and 25 respectively, they had been married at All Saints Parish church the previous year. John and his brother Tom were members of Wigan Cricket Club. (The pair are shown in an early photograph held in Wigan Cricket Club archives, playing at home on 28 June 1862 against Bolton side, Bradford Park CC. John is bowling, with Tom at second slip).

Prisons of the Poor

The workhouse was designed with only a single entrance guarded by the porter, through which inmates and visitors alike had to pass. There was an administration building with offices and a boardroom for the Workhouse Committee, a separate house for the Governor and sleeping quarters for the permanent staff or officers as they were known.

Entrance to Workhouse

Entrance to Workhouse

Also nearby was the receiving or probationary wards, where paupers who were entering the workhouse were housed until a medical officer had examined them. Those suffering from infectious diseases would be placed in a sick ward.

One of the Workhouse buildings

One of the Workhouse buildings

The building consisted of sleeping dormitories, wash rooms, work rooms, day rooms for the elderly, dining hall, school room, store rooms, solitary confinement cell, mortuary, and chapel. In a separate building was the hospital infirmary and imbecile wards. Critics of the design of the new workhouses called them ‘Prisons of the Poor or Pauper Palaces’.

View of the buildings

View of the buildings

People went into the workhouse as a last resort and for a whole variety of reasons. Usually it was because they were too poor, old, or sick to support themselves. Widowed women, or even men, with young children might opt for a spell in the workhouse until their circumstances changed sufficiently to leave. Wives might enter the workhouse because their husband was in jail or had been transported to the Colonies. For unmarried pregnant women who had been disowned by their families the workhouse was the only place they could receive help, during and after the birth of their child. Orphaned or abandoned children invariably ended up in the workhouse. Also prior to the establishment of mental asylums in the mid 1800’s, the mentally ill were usually consigned to the workhouse.

Although life in the workhouse was deliberately harsh with strict rules and a loss of freedom, in some ways it did have its advantages that some on the outside resented. Inmates received three meals a day, even if it was dull monotonous food, healthcare was free and children received a basic education in an effort to give them a better start in life. If possible orphaned children were made indentured apprentices in order to learn a trade and not be a future burden on the parish.

Admission into the workhouse first required an interview by the Union Relieving Officer to establish the applicant’s circumstances. Formal admission into the workhouse proper would then be authorised by the Board of Guardians at their weekly meetings in their Boardroom in Wallgate. By entering a workhouse, paupers were considered to have forfeited responsibility for their families, also, men lost the right to vote. This changed in 1918 following the Suffragette Movement, when women won the right to vote. Accordingly all adults residing in workhouses were able to vote.

After being assessed, the paupers were separated and allocated to the appropriate ward for their category: boys under fourteen, able-bodied men between 14 and 60, men over sixty, girls under 14, able-bodied women between 14 and 60, and women over 60. Mothers could keep children under two years of age with them and have access to any children under seven at all reasonable times.

Clothing and personal possessions were taken from them and stored, to be returned on their discharge. After bathing, they were issued with a rough uniform with the Union mark on them. Inmates were only allowed outside with prior permission, such as to go to a place of worship on a Sunday or attend a baptism or funeral of a relative. The porter locked the outside gate at 9pm every night, handed the keys to the Governor, then he would open up again at 6am the following morning.

However, as harsh as the regime was, the workhouse wasn’t a prison. Any pauper could discharge themselves after giving three hours’ notice, whilst the necessary paperwork was completed. In the case of a married man, if he left, the whole family had to leave. However problems were caused by the so called ‘ins-and-outs’ who treated the workhouse like a boarding house. They would discharge themselves then return a few days, or even hours later, sometimes the worse for drunk, and have to be re-registered all over again.

Workhouse Routine

The 1834 Poor Law Act set out a daily routine for workhouses to follow. In the summer months inmates were woken at 6am by a rising bell. At 6.30 a roll call was held by the Master or Matron in the dining hall, this was followed by breakfast.

Daily work commenced at 7am and ended at 6pm in the evening with an hour off for the mid-day meal. Supper was at 6.30 and inmates had to be in bed with candles out by 8pm. In the winter months, the inmates’ day would start at 7am and they would be in bed by 7pm. Morning and evening prayers were said daily by the Master or Matron, and Grace was said before and after meals. Inmates had to attend Divine Service at a place of worship every Sunday, also on Good Friday and Christmas Day.

Workhouse Food

After 1834 the Poor Law Commission devised a set of six slightly different standard dietaries, from which each Union could select the one it preferred. The Dietary specified the food to be served to each class of inmate (male, female, adult, child etc), for each meal of the week and the exact amount to be provided. The diet in a workhouse varied from one place to another depending on the locality and the local produce available. The Union medical officer would monitor the diet and recommend any changes to the Guardians.

This example is from the No.3 Diet for male able bodied paupers for the day of Wednesday: For breakfast, eight ounces of bread and 1½ pints of gruel. Dinner consisted of eight ounces of cooked meat, ¾ pound of potatoes or vegetables, 1½ pints of soup, seven ounces of bread and 2 ounces of cheese. For supper, the inmate received 6 ounces of bread and 1½ ounces of cheese. Able bodied women received two ounces of bread less for breakfast and one ounce less at supper. For dinner they received two ounces less of cooked meat and ½ ounce less of cheese for both dinner and supper Older inmates of 60 years or over received 7 ounces of tea and 2 ounces of sugar a week in lieu of gruel for breakfast. Children over the age of nine received the same quantities as women. Dining halls were equipped with scales so that inmates could get their food weighed in front of witnesses if they thought it was below the regulation weight.

In the growing season the rations were supplemented by fresh fruit and vegetables grown in an allotment on a piece of land rented from the Rector of Wigan, whose property was adjacent to the workhouse.

Workhouse Labour

The workhouse tried to be self-sustaining and make a profit from the work done by the inmates. Male inmates were employed in the type of work that their respective age and ability would allow. The work might consist of stone-breaking, which was used for road making, crushing bones to be used for fertilizer, crushing rocks of the mineral gypsum into powder, to be used in plastering, sack-making, or oakum picking. Oakum is an old rope, sometimes tarred or knotted. The fibres from these ropes had to be teased out inch by inch by inch and a day's work would be to unravel on average two feet a day. The fibres would then be sold back to ship builders to be used as caulking between the wooden planks of the vessel, which would then be tarred to make it waterproof.

Shortly after the new workhouse opened the committee announced in the minutes that a profit of £27.3s 10d had been made from oakum picking. Hence the saying ‘money for old rope.’

The older less able inmates would usually be employed in the less strenuous job of chopping wood which would then be tied in small bundles and sold for fire lighting. Women had to do domestic work: scrubbing floors, polishing brasses, scrubbing table tops, black-leading kitchen ranges or helping in the kitchen or laundry. Sunday was a day of rest except for essential household and cooking duties.

Rules and Punishment

After 1834, the Poor Law Commission issued detailed orders about every aspect of the Poor Law Union and its workhouses. These rules were updated and added in 1847 and would stay in place for the next 60 years. They were prominently displayed in the workhouse dining hall and also read out at dinner time every Sunday by the Master or Matron, so the illiterate could have no excuse for disobeying them.

Apart from the specific rules regarding the daily routine there were many rules listed, that if broken, would incur the wrath of the Master or Matron and end up with punishment. These included no smoking, no drinking alcohol, no unruly behaviour, swearing or gambling with cards, dice, or games of chance.

The workhouse had a ‘Pauper Offence Book’ which was overseen by the Board of Guardians. The breaking of workhouse rules fell into two categories, firstly ‘Disorderly Conduct‘ which could be punished by the withdrawal of food. Children fighting in school could be denied cheese for one week. Adults found quarrelling could have their meat ration withdrawn for a week. For neglecting your work you could have your dinner meal withheld, with just bread for supper.

Then there was the more serious ‘Refractory Conduct ‘ which could result in a period of solitary confinement in the refractory or punishment cell for a maximum of 24 hours on bread and water, or a visit to the local magistrate and a spell of hard labour in prison. For deliberately breaking a window the punishment could be two months hard labour in prison and for climbing over a wall and deserting the penalty could be a whipping when apprehended. For it was deemed you were stealing the property of the Union, namely the uniform.

National Index of Paupers

Many inmates were to become long term residents of the workhouse, and became institutionalised, forever stuck in the system. On 29th June 1860, The House of Commons ordered that the name of every adult pauper in each workhouse in England and Wales, who had been an inmate for a continuous period of 5 years or more, was to be recorded.

This National Index of Paupers was presented to Parliament on 30 July 1861 and listed 14,216 adults (classed as aged sixteen and over). When compared with the total workhouse population of approximately 67,800 adult workhouse inmates (excluding vagrants) the percentage of long term inmates was just over 21%.

The figures for Wigan show that in 1861, from a total of 275 inmates there were eighty-six long term residents who had been residents of Wigan Union Workhouse for more than five years. A further breakdown shows that thirty-nine were not able to work, 15 were classed as idiots, 13 were of weak intellect, seven were blind, five lame, five elderly and two were suffering from paralysis. The longest serving inmate at the time was Martha Croston, she had been in the workhouse for 30 years.

A Snapshot of Wigan Union Workhouse in 1881

A look at the statistics from the census taken on 3 April 1881 shows that 46 years old John and 45 years old Alice Lowe were still Governor and Matron of Wigan Union Workhouse, they had been running the workhouse for the past 20 years.

They had a staff of nine working under them, six officers and three servants. The assistant matron was 33 years old Ann Hill from Windle, near St. Helens. The nurse in the general hospital, Jane Jones, was from Liverpool and aged sixty. The nurses in the male and female imbecile wards were 39 years old Henry Risby who came from Abingdon in Berkshire and 27 years old Amelia Fuller from Croydon in Surrey. In charge of the school room was teacher Jonathon Caddy, aged twenty-six, from Ulverston and the porter was 37 years old Samuel Parker from Chester. Three locals were employed as servants, Margaret Fairhurst, sixty five, and Elizabeth Appleton aged 43, who worked on the infections and fever wards, respectively. John Taylor aged sixty-five was a painter and odd job man. The medical officer would attend on a regular basis determined by the Board of Guardians or when called for by the Master. The Chaplain would attend daily at a time set by the guardians, read prayers, and preach a sermon to the inmates every Sunday, and on Good Friday and Christmas Day.

A total of 511 inmates, 290 males and 221 females were resident in the workhouse. Of the under fourteens, there 93 boys, 79 girls and 17 infants under the age of two.

All inmates were classified and any disabilities were recorded. The records show that there was one blind and two deaf and dumb inmates, eighty-six were classified as imbeciles, three as idiots, three deaf and dumb imbeciles, and one blind imbecile. Idiots were defined as the most deficient and were unable to protect themselves against basic physical dangers. Imbeciles were a less deficient group and classified as being unable to protect themselves against moral and mental dangers.

The youngest inmate was three weeks old Mary Jane Carson, she was living in the workhouse with her ten year brother Joshua and her unmarried 37 year old mother Ellen, whose occupation was pit brow labourer. The oldest residents were William Wilkinson, a retired brick maker and Timothy Kitchen an ex coal miner, both aged eighty-eight.

Martha Croston, who was mentioned in the 1861 Parliamentary report, was still an inmate in 1881. She died in the workhouse Infirmary, aged eighty-five, having been an inmate for over 50 years. She was buried in a paupers grave, on 7 Feb 1883 in Plot D211 of Wigan Cemetery at Lower Ince.

Paupers Funeral

In medieval times the burials of poor people who couldn’t pay for their own funerals took place in a ‘Potter’s Field,’ whose name has biblical origins. In the early 1500’s the term ‘Pauper’ was used to describe a poor destitute person. A pauper’s funeral usually took place when the deceased was homeless or unknown, with no known next of kin and no money to cover funeral costs.

In Victorian times the term ‘common grave’ replaced pauper’s grave. A common grave is a grave that belongs to the cemetery owner and people who are buried in this kind of plot do not have the ‘exclusive right of burial.’ Unlike a private grave that is purchased by a family or individual and who hold the deeds to the plot.

The local authority had a statutory duty to organise a funeral for any deceased persons who died within their boundaries. For those who didn’t have the means to pay for a private burial, the cemetery personnel would bury people who died over a few days or even weeks, within a single grave. The plot could also be reopened for a further burial at a later date.

Common funerals were very simple affairs with a cheap casket, sometimes reusable, and did not include choice of undertaker, viewings, an obituary, flowers, or a memorial. The deceased would usually be cremated unless they had made a specific wish to be buried. Nowadays the term ‘public grave’ is used as it is a public health funeral and the costs ultimately come out of the public purse.

To this day there is confusion over the names of the two cemeteries in Lower Ince. The larger cemetery, across the railway lines at the end of Cemetery Road, off Warrington Road, was opened in 1856 and named Wigan Cemetery. The following year Ince Cemetery was opened by Ince Urban District Council for the residents of Ince, with its entrance on Warrington Road. In 1974 Ince UDC and the rest of the smaller Borough Councils were abolished following the formation of Wigan Metropolitan Borough. Wigan Cemetery was then renamed Wigan Crematorium & Lower Ince Cemetery.

20th Century

Gradually, by the end of the 19th century things began to change in the workhouse, rules were relaxed and conditions for the inmates, who were mainly the sick and elderly rather than the able bodied poor, began to improve. Still, the problem of vagrancy seemed to be getting worse rather than improving. People were very reluctant to accept the in-relief in a workhouse.

In an attempt to remove the stigma of having been born in a workhouse, the Registrar General decreed that the birth certificate of such individuals born after 1904 should carry a euphemistic address as the place of birth and not one that indicated a workhouse e.g. 75 Frog Lane, Wigan.

In 1904 proposals were put forward for a new workhouse to be built in Billinge, but some members of the Board of Guardians were against the plan owing to the estimated cost of £120,000 which they thought too excessive a burden on the ratepayers of the town. A vote however was in favour and the plans were forwarded onto Local Government for approval.

In the end a compromise was reached and a decision was made to build an infirmary instead, for the use of Wigan Poor Law Union. The infirmary, located on Upholland Road was opened in 1906.

In the same year it was decided to abandon an earlier plan of creating a community village for the paupers in favour of the ‘Scattered Homes’ system. It involved renting suitable houses where the children from the workhouse would be boarded out. They would be under the care of a foster mother who would be paid a yearly income of £25. They in turn would come under the supervision of the master and matron of the workhouse, Mr, and Mrs Alcock. The children would attend elementary school in the week part time, Sunday school and a place of worship appropriate to their religion. Workshops would be fitted out for them to be taught a trade, then at the age of fifteen they would be sent out to work.

Initially five houses were considered suitable and annual rents were agreed on four of them, numbers 13 and 29 Upper Dicconson St at £40, 39 Upper Dicconson St at £27.10s and 214 Ormskirk Road at £18. Springfield Hall in Springfield Road was considered an ideal residence because of its rural location but the rent still had to be agreed on. It had previously been the residence of the Borough treasurer William Trevor Wanklyn, who died that year in Southport.

On Saturday 29 April 1905, a meeting was held in Manchester by the No.11 District of Workhouse Masters and Matrons. On the agenda was the ‘Vagrancy Question.’ The Master of Wigan Union Workhouse Mr. Joseph Edward Alcock addressed the meeting and read a paper entitled ‘The tramp question and how to deal with it.’

He spoke of the vast army of men, women, and children, who wander aimlessly from town to town and spend most of their time in the casual wards. These included the habitual tramps who had no intention of settling down, casual labourers and ex-soldiers. He reserved special criticism for the majority of men and women who tramped about with children, wrongly professed to be man and wife, and gave false names.

Quoting figures from his own workhouse in Wigan he told the meeting that in the last 12 months, 10,605 vagrants had passed through the casual wards, of this total 830 were women and 219 children. He told of the children arriving at the casual wards drenched to the skin and half starved. They never attend school or receive religious education, are brought up to a life of idleness and are taught to steal or beg to exist. Also of concern was the spread of smallpox as many vagrants visiting casual wards had not been vaccinated. He appealed to the Poor Law Board and Government authorities to do something about the situation and change the rules and laws as the number of vagrants was increasing in an alarming manner.

During the Great War of 1914-1918, as battle casualties began to mount, a number of complete workhouse sites were taken over by the military for medical use. By the end of the war over 74,000 beds were being provided to the military by Poor Law Unions. Wigan workhouse was kept running, but Wigan Union handed over Billinge Infirmary for use as a military convalescent hospital. The four hundred bed facility treated over 5,000 soldiers during the conflict, the last patient being discharged on 29 May 1919.

End of an Era

At a meeting on Friday 19 April 1929 the Wigan Board of Guardians appointed Gordon McGregor Esq as it’s last chairman. Following the Local Government Act of 1929 the Wigan Board of Guardians was abolished on 1 April 1930, and responsibility was passed to Wigan Corporation. After three hundred years Wigan Workhouse had finally been consigned to history.

Billinge Infirmary became a general hospital and in 1968 a maternity unit was added. The hospital closed in 2004 and was demolished in 2010 to make way for a new housing development.

Billinge Hospital - original building prior to demolition

Billinge Hospital - original building prior to demolition

On the creation of the National Health Service Act in 1948 the site became the Frog Lane Welfare Home, caring for geriatric residents. However the stigma associated with the workhouse continued and many people were reluctant to enter the home or even visit relatives.

In the 1960’s St. Stephen’s house, which was the home to forty elderly people, was closed and it’s residents re-housed at Bottling Wood in Whelley, the building was demolished in 1969. The workhouse was then slowly demolished in phases, the hospital block was closed in 1972 and it’s patients were moved to a new wing at Billinge Hospital. For a period homeless families were temporarily housed on the site. The remaining buildings were finally demolished in the 1990’s.

Part of the site, at the Woodhouse Lane end was utilised by Wigan Council as a youth trade training centre for a number of years, before closing and moving to a new site. Eventually the whole of the fifteen acre Workhouse site was redeveloped and is now shared by the NHS in the form of Boston House Health Centre and new housing, which is accessed via Frog Lane and Gidlow Lane.

Today the only reminder of a long lost institution are sections of the original workhouse boundary walls which are still in situ and can be seen along Frog Lane and the rear of Diggle St, bordering the children's playground.

Graham Taylor - 2021

Sources:-

Ancestry UK, British Newspaper Archives, Family Search, Historic UK, Key dates in the sociological history of GB, National Archives, Parliament UK, The Alms-house Association, The Victorian Society, Victorian Era Workhouses, Wideopen 1997, George Bell, Wigan Archives, Wigan Observer & District Advertiser, Wikipedia – the Workhouses, Workhouses website by Peter Higginbotham, WLHHS – Peter Fleetwood.

Photographs

Ron Hunt, Wigan World